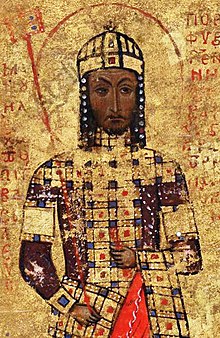

Alexios Komnenos (protosebastos)

The plot was discovered and most conspirators arrested, but Maria and her husband fled to the Hagia Sophia, protected by Patriarch Theodosios Borradiotes and the common people of Constantinople.

Mounting tensions resulted in a popular uprising against Alexios' regime on 2 May 1181, (modern scholars have proposed other dates as well), which ended in a mutual reconciliation.

These events left Alexios in poor shape to oppose the advance of the adventurer Andronikos I Komnenos, who moved against Constantinople from the east.

[3] In his prosopographical study of the Komnenoi, the Greek scholar, Konstantinos Varzos, placed his birth on Easter Day 1135 (or possibly 1134 or 1136), as he was old enough to participate in a campaign in 1149/50.

[6][7] The Prosopography of the Byzantine World database, on the other hand, interprets the poems by Prodromos as indicating that Alexios was born in 1142, during his father's absence on the campaign that cost his life.

[13] Sometime during his tenure as prōtostratōr, Alexios fell gravely ill, and his wife donated a richly embroidered veil to the Church of the Saviour at the Chalke Gate, an occasion celebrated by an anonymous court poet.

His first mission concerned the marriage of his cousin Eudokia—daughter of his paternal uncle Isaac—to Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Provence, brother of King Alfonso II of Aragon.

Although after Manuel's death she had become a nun, the Empress-dowager immediately became the focus of attention of ambitious suitors who sought to win her affection, and supreme power along with it.

Although this was apparently widely believed at the time, modern scholars like Varzos are doubtful, as the Byzantine sources are themselves divided over the matter: while the contemporary official and historian, Niketas Choniates, reports the rumours almost as fact, the 13th-century chronicler Theodore Skoutariotes appears to have considered them baseless.

[26] Whether or not Alexios intended to usurp the throne his concentration of power alarmed the other imperial relatives, above all Emperor Manuel's daughter from his first marriage, the porphyrogennētē princess Maria Komnene.

According to this interpretation, the primary concern of the opposition was the prōtosebastos' domination of the government, which had destroyed the previous arrangements under Manuel, where the court aristocracy had been "equal in power".

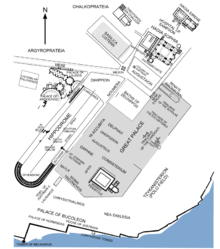

A soldier betrayed the conspiracy, however, and most of its members were arrested, tried by a tribunal under the dikaiodotēs Theodore Pantechnes—who succeeded Kamateros as eparch—and imprisoned in the dungeons of the Great Palace.

Andronikos Lapardas managed to escape, while the Caesarissa Maria and her husband sought refuge in the Hagia Sophia, where she soon gained the support not only of the Patriarch Theodosios Borradiotes but also of the common people, who took pity on her plight and her imperial descent, and who were further won over because of her largesse in distributing coins to the crowd.

[32][33] Emboldened by the popular support, the princess refused Alexios' offers of an amnesty, demanding not only a retrial of her co-conspirators but also the immediate dismissal of the prōtosebastos from the palace and the administration.

When the Empress-dowager and the prōtosebastos had Alexios II issue a warning to his half-sister that she would be evicted by force, she again refused, and despite the Patriarch's angry objections started posting her followers to keep watch over the entrances to the great church, recruiting even "Italians in heavy armor and stouthearted Iberians from the East who had come to the City for commercial purposes", as Choniates reports.

Led by three priests, the populace was driven to rebellion, and over several days they not only demonstrated before the gates of the palace but also ransacked several mansions of the nobility, including that of Pantechnes.

In the meantime, Princess Maria's supporters barricaded themselves behind the Augoustaion square between the Great Palace and the Hagia Sophia, after they razed the adjoining buildings.

The Caesar Renier rallied about 150 of his men from his own Latin bodyguards and his wife's servants and followers, gave a speech justifying their struggle, and led them forth against the imperial troops in the Augoustaion, who retreated hastily and in confusion.

She would not be deprived of her dignities and privileges by her brother the emperor, or her stepmother the empress, or the prōtosebastos Alexios, and full amnesty would be granted her supporters and allies", as Choniates reports.

[40] Despite the failure of the revolt, the position of the prōtosebastos was weakened: on the one hand, his readiness to use force against fellow citizens, even in the most hallowed of all churches in the Empire, increased popular hostility, while on the other, the amnesty offered to Maria and her supporters strengthened the perception of the regime's weakness.

His triumphal return, with jubilant crowds lining the procession that led him back to the patriarchal palace near the Hagia Sophia, was another blow to the regime's authority.

[48][49] In autumn 1181, Andronikos began his march against Constantinople, proceeding slowly to give the impression of a large and cumbersome force, and allowing time for his propaganda to have an impact.

[52][53] Nevertheless, the army sent by the government, under Andronikos Angelos (the father of the future emperors Isaac II and Alexios III), was defeated at Charax near Nicomedia, even though according to Choniates it faced only "farmers unfit for warfare and a contingent of Paphlagonian soldiers".

Fearing accusations of pro-Andronikos sentiments, he barricaded himself and his family in their mansion, before fleeing the city altogether and joining Andronikos Komnenos in Bithynia.

Alexios attempted to negotiate, and sent George Xiphilinos (a future patriarch) to Andronikos' camp, offering a pardon and high office.

After a few days he was led, seated on a pony and preceded by a reed flag in mockery of a banner amidst the jeers and abuse of the populace, to a fishing boat and across to Chalcedon.