Almagest

The Almagest (/ˈælmədʒɛst/ AL-mə-jest) is a 2nd-century mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy (c. AD 100 – c. 170) in Koine Greek.

[1] One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canonized a geocentric model of the Universe that was accepted for more than 1,200 years from its origin in Hellenistic Alexandria, in the medieval Byzantine and Islamic worlds, and in Western Europe through the Middle Ages and early Renaissance until Copernicus.

[citation needed] The work was originally called Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις (Mathēmatikḕ Sýntaxis) in Koine Greek, and was also known as Syntaxis Mathematica in Latin.

It is significant that Ptolemy chooses the ecliptical coordinate system because of his knowledge of precession, which distinguishes him from all his predecessors.

For example, the Greek letters Α and Δ were used to mean 1 and 4 respectively, but because these look similar copyists sometimes wrote the wrong one.

Some errors may be due to atmospheric refraction causing stars that are low in the sky to appear higher than where they really are.

Ptolemy inherited from his Greek predecessors a geometrical toolbox and a partial set of models for predicting where the planets would appear in the sky.

Hipparchus had some knowledge of Mesopotamian astronomy, and he felt that Greek models should match those of the Babylonians in accuracy.

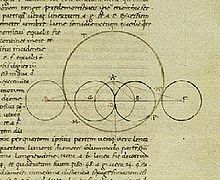

It explained geometrical models of the planets based on combinations of circles, which could be used to predict the motions of celestial objects.

The first translations into Arabic were made in the 9th century, with two separate efforts, one sponsored by the caliph Al-Ma'mun, who received a copy as a condition of peace with the Byzantine emperor.

The German astronomer Johannes Müller (known as Regiomontanus, after his birthplace of Königsberg) made an abridged Latin version at the instigation of the Greek churchman Cardinal Bessarion.

Around the same time, George of Trebizond made a full translation accompanied by a commentary that was as long as the original text.

[citation needed] During the 16th century, Guillaume Postel, who had been on an embassy to the Ottoman Empire, brought back Arabic disputations of the Almagest, such as the works of al-Kharaqī, Muntahā al-idrāk fī taqāsīm al-aflāk ("The Ultimate Grasp of the Divisions of Spheres", 1138–39).

Under the scrutiny of modern scholarship, and the cross-checking of observations contained in the Almagest against figures produced through backwards extrapolation, various patterns of errors have emerged within the work.

[34][35] A prominent example is Ptolemy's use of measurements said to have been taken at noon, but which systematically produce readings that are off by half an hour, as if the observations were taken at 12:30pm.

[34] Bernard R. Goldstein wrote, "Unfortunately, Newton’s arguments in support of these charges are marred by all manner of distortions, misunderstandings, and excesses of rhetoric due to an intensely polemical style.

"[36] Owen Gingerich, while agreeing that the Almagest contains "some remarkably fishy numbers",[34] including in the matter of the 30-hour displaced equinox, which he noted aligned perfectly with predictions made by Hipparchus 278 years earlier,[39] rejected the qualification of fraud.

Newton, "I think that his main conclusion with respect to Ptolemy’s stature and achievements as an astronomer is simply wrong, and that the Almagest should be seen as a great, if not indeed the first, scientific treatise."

He continued, "Newton’s work does focus critical attention on the many difficulties and inconsistencies apparent in the fine structure of the Almagest.

"[38] The Almagest under the Latin title Syntaxis mathematica, was edited by J. L. Heiberg in Claudii Ptolemaei opera quae exstant omnia, vols.

The first, by R. Catesby Taliaferro of St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland, was included in volume 16 of the Great Books of the Western World in 1952.

[42] A direct French translation from the Greek text was published in two volumes in 1813 and 1816 by Nicholas Halma, including detailed historical comments in a 69-page preface.

It has been described as "suffer[ing] from excessive literalness, particularly where the text is difficult" by Toomer, and as "very faulty" by Serge Jodra.