Alphabet

Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from another in a given language.

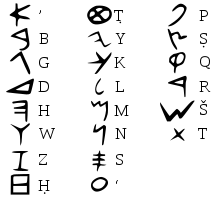

The Phoenician system is considered the first true alphabet and is the ultimate ancestor of many modern scripts, including Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and possibly Brahmic.

Abjads generally lack vowel indicators altogether, while abugidas represent them with diacritics added to letters.

More recently however, four cylinder seals dating to 2400 BC and found at the site of Umm el-Marra, in present-day Syria, are incised with what is potentially the earliest known alphabetic writings in the world.

The discovery suggests that the alphabet emerged 500 years earlier than previously thought, and undermines leading ideas about how it was invented.

[14][15][16][17] According to Christopher Rollston, a scholar of the ancient Near East, the morphology of the letters on the cylinder seals parallels quite nicely that of the existing corpus of early alphabetic writing.

[20] The Ancient Egyptian writing system had a set of some 24 hieroglyphs that are called uniliterals,[21] which are glyphs that provide one sound.

[22] These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names.

Orly Goldwasser has connected the illiterate turquoise miner graffiti theory to the origin of the alphabet.

[9] In 1999, American Egyptologists John and Deborah Darnell discovered an earlier version of this first alphabet at the Wadi el-Hol valley.

The Runic alphabets were used for Germanic languages from 100 CE to the late Middle Ages, being engraved on stone and jewelry, although inscriptions found on bone and wood occasionally appear.

[47][better source needed] The creation of Hangul was planned by the government of the day,[48] and it places individual letters in syllable clusters with equal dimensions, in the same way as Chinese characters.

This change allows for mixed-script writing, where one syllable always takes up one type space no matter how many letters get stacked into building that one sound-block.

Following the proclamation of the People's Republic of China in 1949 and its adoption of Hanyu Pinyin in 1956, the use of bopomofo on the mainland is limited.

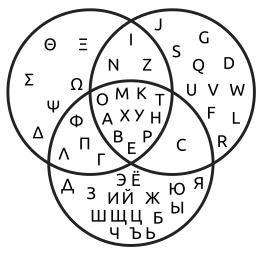

In a broader sense, an alphabet is a segmental script at the phoneme level—that is, it has separate glyphs for individual sounds and not for larger units such as syllables or words.

In the narrower sense, some scholars distinguish "true" alphabets from two other types of segmental script, abjads, and abugidas.

[52][53] Examples of present-day abjads are the Arabic and Hebrew scripts;[54] true alphabets include Latin, Cyrillic, and Korean hangul; and abugidas, used to write Tigrinya, Amharic, Hindi, and Thai.

The Canadian Aboriginal syllabics are also an abugida, rather than a syllabary, as their name would imply, because each glyph stands for a consonant and is modified by rotation to represent the following vowel.

Some alphabets disregard tone entirely, especially when it does not carry a heavy functional load,[62] as in Somali and many other languages of Africa and the Americas.

[67][68] In German, words starting with sch- (which spells the German phoneme /ʃ/) are inserted between words with initial sca- and sci- (all incidentally loanwords) instead of appearing after the initial sz, as though it were a single letter, which contrasts several languages such as Albanian, in which dh-, ë-, gj-, ll-, rr-, th-, xh-, and zh-, which all represent phonemes and considered separate single letters, would follow the letters ⟨d, e, g, l, n, r, t, x, z⟩ respectively, as well as Hungarian and Welsh.

An exception is the German telephone directory, where umlauts are sorted like ä=ae since names such as Jäger also appear with the spelling Jaeger and are not distinguished in the spoken language.

One, the ABCDE order later used in Phoenician, has continued with minor changes in Hebrew, Greek, Armenian, Gothic, Cyrillic, and Latin; the other, HMĦLQ, was used in southern Arabia and is preserved today in Geʻez.

[citation needed] The Brahmic family of alphabets used in India uses a unique order based on phonology: The letters are arranged according to how and where the sounds get produced in the mouth.

This organization is present in Southeast Asia, Tibet, Korean hangul, and even Japanese kana, which is not an alphabet.

This is called acrophony and is continuously used to varying degrees in Samaritan, Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic.

By contrast, the names of F, L, M, N, and S (/ɛf, ɛl, ɛm, ɛn, ɛs/) remain the same in both languages because "short" vowels were largely unaffected by the Shift.

Some national languages like Finnish, Armenian, Turkish, Russian, Serbo-Croatian (Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian), and Bulgarian have a very regular spelling system with nearly one-to-one correspondence between letters and phonemes.

[97] In standard Spanish, one can tell the pronunciation of a word from its spelling, but not vice versa, as phonemes sometimes can be represented in more than one way, but a given letter is consistently pronounced.

French using silent letters, nasal vowels, and elision, may seem to lack much correspondence between the spelling and pronunciation.

[104][105] The standard system of symbols used by linguists to represent sounds in any language, independently of orthography, is called the International Phonetic Alphabet.