Alpine lake

[5] Due to the importance of alpine lakes as sources of freshwater for agricultural and human use, the physical, chemical, and biological responses to climate change are being extensively studied.

These dams of debris can be very resilient or may burst, causing extreme flooding which poses significant hazards to communities in the alpine, especially in the Himalayas.

[citation needed] The annual cycle of stratification and mixing in lakes plays a significant role in determining vertical distribution of heat, dissolved chemicals, and biological communities.

[12] Most alpine lakes exist in temperate or cold climates characteristic of their high elevation, leading to a dimictic mixing regime.

High altitude regions are experiencing changing seasonal weather patterns and faster warming than the global average.

[18] A change in mixing regime could fundamentally alter chemical and biological conditions such as nutrient availability and the timing and duration of hypoxia in alpine lakes.

[18] In addition, the relatively small size and high altitude of alpine lakes may make them especially susceptible to changes in climate.

[19] The hydrology of an alpine lake's watershed plays a large role in determining chemical characteristics and nutrient availability.

[23] Alpine lakes are often situated in mountainous regions near or above the treeline which leads to steep watersheds with underdeveloped soil and sparse vegetation.

[22] Clear alpine lakes have low concentrations of suspended sediment and turbidity which can be caused by a lack of erosion in the watershed.

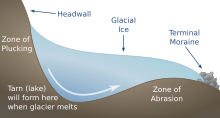

Glacier-fed lakes have much higher suspended sediment concentrations and turbidity due to inflow of glacial flour, resulting in opaqueness and a bright blue or brown color.

[24][21] Circulation in alpine lakes can be caused by wind, river inflows, density currents, convection, and basin-scale waves.

Steep topography characteristic of alpine lakes can partially shield them from wind generated by regional weather patterns.

[30] This vertical circulation is an efficient means for mixing in lakes[30] and may play a significant role in homogenizing the water column between periods of stratification.

[33] Phytoplankton populations are dominated by nanoplanktonic, mobile species including chrysophytes, dinoflagellates, and cryptophytes in the water column, with important contributions to photosynthesis also coming from the algae community attached to substrates, epilithon and epipelon.

For example, at higher altitudes, alpine lakes experience shorter ice-free periods which places a limit on the amount of primary production and subsequent growth of food.

In conclusion, both the lake's physical features, including size and substrate, and environmental parameters, including temperature and ice-cover, define community composition and structure, with one study suggesting that temperature and altitude are the primary drivers,[36] and another presenting evidence instead for heterogeneity in lake morphometry and substrate as the primary drivers.

[33] All of these environmental parameters are likely to be impacted by climate change, with cascading effects on alpine lake invertebrate and microbial communities.

Crater Lake did not hold any vertebrate species before a stocking event between 1884 and 1941 of 1.8 million salmonids, mainly Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and kokanee salmon (O.

Bringing in non-native species, especially to fishless lakes, can also carry pathogens and bacteria, negatively impacting the invertebrate community already there.

Alpine lake ecosystems are undergoing unprecedented rates of change in community composition in relation to recent temperature increases and nutrient loading.

[37][44] Trace elements can occur naturally, but industrialization, including the consumption of fossil fuels, has accelerated their rate of accumulation into alpine lake environments.

After being released into the atmosphere, trace elements can become soluble through biogeochemical processes and end up in sediment and then mobilized through weathering and runoff to enter alpine lake ecosystems.

[32] Another study, upon assessing the composition through time of chosen bioindicators and finding evidence for degraded water quality, concluded that the lake ecosystem had moved out of a "safe operational state".

[45] Alkalinity in natural waters is largely due to bicarbonate, the strong conjugate base of the weak carbonic acid, that is the product of rock weathering.

[citation needed] Alpine lakes have been well studied in regard to acidification since the 1980s largely because of the seasonal patterns of alkalinity and pH changes that they naturally exhibit from precipitation and snowmelt.

[48] The weather patterns of alpine lakes include large periods of snowmelt which has extended contact with soil and rock resulting in increased alkalinity.

Thus, by understanding these mechanisms of the past, better predictions can be made about the future response of alpine ecosystems to present-day climate change.

For instance, an alpine lake in the Coast Mountains of British Columbia revealed cooler and wetter conditions due to the increased trend in mineral-rich (glacial-derived) P sediments which agrees with other findings of cooling in the Holocene.

[57] During periods of warmer temperatures, extended growing seasons led to more benthic plant growth which is revealed by more periphytic (substrate-growing) diatom species.