Dendrochronology

As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, the study of climate and atmospheric conditions during different periods in history from the wood of old trees.

However, for a precise date of the death of the tree a full sample to the edge is needed, which most trimmed timber will not provide.

It also gives data on the timing of events and rates of change in the environment (most prominently climate) and also in wood found in archaeology or works of art and architecture, such as old panel paintings.

As of 2024, only three areas have continuous sequences going back to prehistoric times, the foothills of the Northern Alps, the southwestern United States and the British Isles.

[8][9] In his Trattato della Pittura (Treatise on Painting), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was the first person to mention that trees form rings annually and that their thickness is determined by the conditions under which they grew.

[10] In 1737, French investigators Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau and Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon examined the effect of growing conditions on the shape of tree rings.

[11] They found that in 1709, a severe winter produced a distinctly dark tree ring, which served as a reference for subsequent European naturalists.

[13] The English polymath Charles Babbage proposed using dendrochronology to date the remains of trees in peat bogs or even in geological strata (1835, 1838).

In 1859, the German-American Jacob Kuechler (1823–1893) used crossdating to examine oaks (Quercus stellata) in order to study the record of climate in western Texas.

[15] In 1866, the German botanist, entomologist, and forester Julius Theodor Christian Ratzeburg (1801–1871) observed the effects on tree rings of defoliation caused by insect infestations.

[19] From 1869 to 1901, Robert Hartig (1839–1901), a German professor of forest pathology, wrote a series of papers on the anatomy and ecology of tree rings.

[20] In 1892, the Russian physicist Fedor Nikiforovich Shvedov [ro; ru; uk] (1841–1905) wrote that he had used patterns found in tree rings to predict droughts in 1882 and 1891.

[21] During the first half of the twentieth century, the astronomer A. E. Douglass founded the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona.

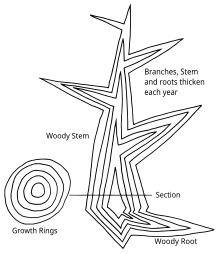

[23][better source needed] Many trees in temperate zones produce one growth-ring each year, with the newest adjacent to the bark.

First, contrary to the single-ring-per-year paradigm, alternating poor and favorable conditions, such as mid-summer droughts, can result in several rings forming in a given year.

[24] Critical to the science, trees from the same region tend to develop the same patterns of ring widths for a given period of chronological study.

When one can match these tree-ring patterns across successive trees in the same locale, in overlapping fashion, chronologies can be built up—both for entire geographical regions and for sub-regions.

Dendrochronologists originally carried out cross-dating by visual inspection; more recently, they have harnessed computers to do the task, applying statistical techniques to assess the matching.

[27] Another fully anchored chronology that extends back 8,500 years exists for the bristlecone pine in the Southwest US (White Mountains of California).

where ΔL is width of annual ring, t is time (in years), ρ is density of wood, kv is some coefficient, M(t) is function of mass growth of the tree.

Ignoring the natural sinusoidal oscillations in tree mass, the formula for the changes in the annual ring width is:

[32] European chronologies derived from wooden structures initially found it difficult to bridge the gap in the fourteenth century when there was a building hiatus, which coincided with the Black Death.

[citation needed] Miyake events, such as the ones in 774–775 and 993–994, can provide fixed reference points in an unknown time sequence as they are due to cosmic radiation.

[36] For example, wooden houses in the Viking site at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland were dated by finding the layer with the 993 spike, which showed that the wood is from a tree felled in 1021.

[37] Researchers at the University of Bern have provided exact dating of a floating sequence in a Neolithic settlement in northern Greece by tying it to a spike in cosmogenic radiocarbon in 5259 BC.

[30] This can be done by checking radiocarbon dates against long master sequences, with Californian bristle-cone pines in Arizona being used to develop this method of calibration as the longevity of the trees (up to c.4900 years) in addition to the use of dead samples meant a long, unbroken tree ring sequence could be developed (dating back to c. 6700 BC).

However, unlike analysis of samples from buildings, which are typically sent to a laboratory, wooden supports for paintings usually have to be measured in a museum conservation department, which places limitations on the techniques that can be used.

Similar seasonal patterns also occur in ice cores and in varves (layers of sediment deposition in a lake, river, or sea bed).

Some columnar cacti also exhibit similar seasonal patterns in the isotopes of carbon and oxygen in their spines (acanthochronology).

A similar technique is used to estimate the age of fish stocks through the analysis of growth rings in the otolith bones.