American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

L. 111–5 (text) (PDF)), nicknamed the Recovery Act, was a stimulus package enacted by the 111th U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Barack Obama in February 2009.

Other objectives were to provide temporary relief programs for those most affected by the recession and invest in infrastructure, education, health, and renewable energy.

On January 10, 2009, President-Elect Obama's administration released a report[12] that provided a preliminary analysis of the impact to jobs of some of the prototypical recovery packages that were being considered.

On January 23, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi said that the bill was on track to be presented to President Obama for him to sign into law before February 16, 2009.

Republicans proposed several amendments to the bill directed at increasing the share of tax cuts and downsizing spending as well as decreasing the overall price.

While in favor of a stimulus package, Feldstein expressed concern over the act as written, saying it needed revision to address consumer spending and unemployment more directly.

[69] Just after the bill was enacted, Krugman wrote that the stimulus was too small to deal with the problem, adding, "And it's widely believed that political considerations led to a plan that was weaker and contains more tax cuts than it should have – that Mr. Obama compromised in advance in the hope of gaining broad bipartisan support.

[71] On January 28, 2009, a full-page advertisement with the names of approximately 200 economists who were against Obama's plan appeared in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

This included Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences laureates Edward C. Prescott, Vernon L. Smith, and James M. Buchanan.

The economists denied the quoted statement by President Obama that there was "no disagreement that we need action by our government, a recovery plan that will help to jumpstart the economy".

Instead, the signers believed that "to improve the economy, policymakers should focus on reforms that remove impediments to work, saving, investment and production.

[73] On February 8, 2009, a letter to Congress signed by about 200 economists in favor of the stimulus, written by the Center for American Progress Action Fund, said that Obama's plan "proposes important investments that can start to overcome the nation's damaging loss of jobs", and would "put the United States back onto a sustainable long-term-growth path".

[74] This letter was signed by Nobel Memorial laureates Kenneth Arrow, Lawrence R. Klein, Eric Maskin, Daniel McFadden, Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow.

[78] A 2013 study by economists Stephen Marglin and Peter Spiegler found the stimulus had boosted GDP in line with CBO estimates.

[78] In February 2015, the CBO released its final analysis of the results of the law, which found that during six years:[82] A May 21, 2009, article in The Washington Post stated, "To build support for the stimulus package, President Obama vowed unprecedented transparency, a big part of which, he said, would be allowing taxpayers to track money to the street level on Recovery.gov..." But three months after the bill was signed, Recovery.gov offers little beyond news releases, general breakdowns of spending, and acronym-laden spreadsheets and timelines."

The same article also stated, "Unlike the government site, the privately run Recovery.org is actually providing detailed information about how the $787 billion in stimulus money is being spent.

A statement released by the USDA the same day corrected the allegation, stating that "references to '2 pound frozen ham sliced' are to the sizes of the packaging.

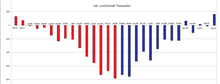

[89] On February 12, 2010, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which regularly issues economic reports, published job-loss data on a month-by-month basis since 2000.

"[91] Others argue that job losses always grow early in a recession and naturally slow down with or without government stimulus spending, and that the OFA chart was misleading.

In the primary justification for the stimulus package, the Obama administration and Democratic proponents presented a graph in January 2009 showing the projected unemployment rate with and without the ARRA.

The aspects of the stimulus expected by the NABE to have the greatest effectiveness were physical infrastructure, unemployment benefits expansion, and personal tax-rate cuts.

Economist Dean Baker commented: [T]he revised data ... showed that the economy was plunging even more rapidly than we had previously recognised in the two quarters following the collapse of Lehman.

"[103] In July 2010, the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) estimated that the stimulus had "saved or created between 2.5 and 3.6 million jobs as of the second quarter of 2010".

Using a straight mathematical calculation, critics reported that the ARRA cost taxpayers between $185,000 to $278,000 per job that was created, though this computation does not include the permanent infrastructure that resulted.

The two senators did concede that the stimulus has had a positive effect on the economy, though they criticized it for failing to give "the biggest bang for our buck" on the issue of job creation.

CNN noted that the two senators' stated objections were brief summaries presenting selective accounts that were unclear, and the journalists pointed out several instances where they created erroneous impressions.

[116] These results cast doubt on previously stated estimates of job creation numbers, which do not factor those companies that did not retain their workers or hire any at all.

In February 2014, the White House stated in a release that the stimulus measure saved or created an average of 1.6 million jobs a year between 2009 and 2012, thus averting having the recession descend into another Great Depression.

As well, the President named Inspector General of the United States Department of the Interior Earl Devaney and the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board (RATB) to monitor administration of the Act, and prevent low levels of fraud, waste and loss in fund allocation.

In late 2011, Devaney and his fellow inspectors general on RATB, and more who were not, were credited with avoiding any major scandals in the administration of the Act, in the eyes of one Washington observer.

Tax incentives – Includes $15 B for Infrastructure and Science, $61 B for Protecting the Vulnerable, $25 B for Education and Training and $22 B for Energy, so total funds are $126 B for Infrastructure and Science, $142 B for Protecting the Vulnerable, $78 B for Education and Training, and $65 B for Energy.

State and Local Fiscal Relief – Prevents state and local cuts to health and education programs and state and local tax increases.