American juvenile justice system

The juvenile justice system intervenes in delinquent behavior through police, court, and correctional involvement, with the goal of rehabilitation.

[1] Early debates questioned whether there should be a separate legal system for punishing juveniles, or if juveniles should be sentenced in the same manner as adults[3] With the changing demographic, social, and economic context of the 19th century resulting largely from industrialization, "the social construction of childhood...as a period of dependency and exclusion from the adult world" was institutionalized.

Barry Krisberg and James F. Austin note that the first ever institution dedicated to juvenile delinquency was the New York House of Refuge in 1825.

[5] Other programs, described by Finley, included: "houses of refuge", which emphasized moral rehabilitation; "reform schools", which had widespread reputations for mistreatment of the children living there; and "child saving organizations", social charity agencies dedicated to reforming poor and delinquent children.

Prior to this ideological shift, the application of parens patriae was restricted to protecting the interests of children, deciding guardianship and commitment of the mentally ill.

In the 1839 Pennsylvania landmark case, Ex parte Crouse, the court allowed use of parens patriae to detain young people for non-criminal acts in the name of rehabilitation.

[6][7] Since these decisions were carried out "in the best interest of the child," the due process protections afforded adult criminals were not extended to juveniles.

In enforcing the truancy laws, Progressive Era judges and educators relied on teachers' report cards to monitor the behavior of probationers.

[13] The creation of the juvenile justice system in Chicago coincided with the migration of southern black families to the North.

In one case a 13 year old Kentuckian was accused of "habitual truancy" by the principal of his school, which would have been a violation of compulsory education laws, but the principal herself admitted that his attendance was perfect and that she had filed a petition for him to be sent to a Parental School because his parents were not giving him adequate care and "something should be done to keep him off the streets and away from bad company".

[3] While still recommending harsher punishments for serious crimes,[15] "community-based programs, diversion, and deinstitutionalization became the banners of juvenile justice policy in the 1970's".

[3] Schools and politicians adopted zero-tolerance policies with regard to crime and argued that rehabilitative approaches were less effective than strict punishment.

As Loyola law professor Sacha Coupet argues, "[o]ne way in which "get tough" advocates have supported a merger between the adult criminal and juvenile systems is by expanding the scope of transfer provisions or waivers that bring children under the jurisdiction of the adult criminal system".

The "three strikes laws" that began in 1993 fundamentally altered the criminal offenses that resulted in detention, imprisonment, and even a life sentence, for both youth and adults.

[22] Implementation of the Gun-Free School Act (GFSA) in 1994 is one example of a "tough on crime" policy that has contributed to increased numbers of young people being arrested and detained.

[25] The number of cases handled by the juvenile courts in the United States was 1,159,000 in 1985, and increased steadily until 1998, reaching a high point of 1,872,700.

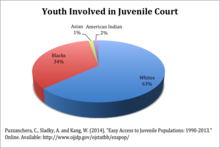

[28] The current debate on juvenile justice reform in the United States focuses on the root of racial and economic discrepancies in the incarcerated youth population.

The most common is the implementation of zero tolerance policies which have increased the numbers of young people being removed from classrooms, often for minor infractions.

[30] Collectively this creates the school-to-prison pipeline - a phenomenon that contributes to more students falling behind, dropping out and eventually being funneled into the juvenile justice system.

[3] Research on juvenile incarceration and prosecution indicates that criminal activity is influenced by positive and negative life transitions regarding the completion of education, entering the workforce, and marrying and beginning families.

[31] According to certain developmental theories, adolescents who are involved in the court system are more likely to experience disruption in their life transitions, leading them to engage in delinquent behavior as adults.

Finley argues for early intervention in juvenile delinquency, and advocates for the development of programs that are more centered on rehabilitation rather than punishment.

[3] James C. Howell et al. argue that zero tolerance policies overwhelm the juvenile justice system with low risk offenders and should be eliminated.

They argue that educational reentry programs should be developed and given high importance alongside policies of dropout prevention.

[5] Some popular suggested reforms to juvenile detention programs include changing policies regarding incarceration and funding.

One recommendation from the Annie E. Casey Foundation is restricting the offenses that are punishable by incarceration, so that only youth who present a threat to public safety are confined.

As Butts, Mayer and Ruther describe, "The concepts underlying PYD resemble those that led to the founding of the american juvenile justice system more than a century ago.

The underlying thesis of restorative practices is that ‘‘human beings are happier, more cooperative and productive, and more likely to make positive changes in their behavior when those in positions of authority do things with them, rather than to or for them.’’[46] Many advocates argue that the juvenile system should extend to include young adults 18 or older (the age that most systems use as a cut-off).

Research in neurobiology and developmental psychology show that young adults' brains do not finish developing until their mid-20s, well beyond the age of criminal responsibility in most states.

[47] Other non-criminal justice systems acknowledge these differences between adults and young people with laws about drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, etc.