United States corporate law

[11] It was possible to sell voteless shares in the economic boom of the 1920s, because more and more ordinary people were looking to the stock market to save the new money they were earning, but the law did not guarantee good information or fair terms.

Because many shareholders were physically distant from corporate headquarters where meetings would take place, new rights were made to allow people to cast votes via proxies, on the view that this and other measures would make directors more accountable.

The incorporators will also have to adopt "bylaws" which identify many more details such as the number of directors, the arrangement of the board, requirements for corporate meetings, duties of officer holders and so on.

[27] An intermediate viewpoint in the academic literature,[28] suggested that regulatory competition could in fact be either positive or negative, and could be used to the advantage of different groups, depending on which stakeholders would exercise most influence in the decision about which state to incorporate in.

At its center, corporations being "legal persons" mean they can make contracts and other obligations, hold property, sue to enforce their rights and be sued for breach of duty.

For example, in an 1869 case named Paul v Virginia, the US Supreme Court held that the word "citizen" in the privileges and immunities clause of the US Constitution (article IV, section 2) did not include corporations.

[33] By contrast, in Santa Clara County v Southern Pacific Railroad Co,[34] a majority of the Supreme Court hinted that a corporation might be regarded as a "person" under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Southern Pacific Railroad Company had claimed it should not be subject to differential tax treatment, compared to natural persons, set by the State Board of Equalization acting under the Constitution of California.

Initially, in Buckley v Valeo[36] a slight majority of the US Supreme Court had held that natural persons were entitled to spend unlimited amounts of their own money on their political campaigns.

[37] A differently constituted US Supreme Court held, with three dissents, that the Michigan Campaign Finance Act could, compatibly with the First Amendment, prohibit political spending by corporations.

In a five to four decision, Citizens United v Federal Election Commission[35] held that corporations were persons that should be protected in the same was as natural people under the First Amendment, and so they were entitled to spend unlimited amounts of money in donations to political campaigns.

Subsequently, the same Supreme Court majority decided in 2014, in Burwell v Hobby Lobby Stores Inc[38] that corporations were also persons for the protection of religion under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

The dissenting four judges emphasized their view that previous cases provided "no support for the notion that free exercise [of religious] rights pertain to for-profit corporations.

Toward the outside world, the acts of directors, officers and other employees will be binding on the corporation depending on the law of agency and principles of vicarious liability (or respondeat superior).

Shareholders also often have rights to amend the corporate constitution, call meetings, make business proposals, and have a voice on major decisions, although these can be significantly constrained by the board.

Most state laws, and the federal government, give a broad freedom to corporations to design the relative rights of directors, shareholders, employees and other stakeholders in the articles of incorporation and the by-laws.

While the board of directors is generally conferred the power to manage the day-to-day affairs of a corporation, either by the statute, or by the articles of incorporation, this is always subject to limits, including the rights that shareholders have.

The DGCL §141(k) gives an option to corporations to have a unitary board that can be removed by a majority of members "without cause" (i.e. a reason determined by the general meeting and not by a court), which reflects the old default common law position.

[93] On a number of issues that are seen as very significant, or where directors have incurable conflicts of interest, many states and federal legislation give shareholders specific rights to veto or approve business decisions.

By contrast, larger and collective pension funds, many still defined benefit schemes such as CalPERS or TIAA, organize to take voting in house, or to instruct their investment managers.

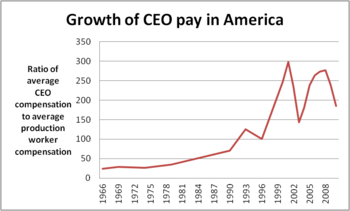

[112] The United States is in a minority of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries that, as yet, has no law requiring employee voting rights in corporations, either in the general meeting or for representatives on the board of directors.

Corporations are chartered under state law, the larger mostly in Delaware, but leave investors free to organize voting rights and board representation as they choose.

[123] This position was eventually reversed expressly by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 §971, which subject to rules by the Securities and Exchange Commission entitles shareholders to put forward nominations for the board.

"[142] The standards applicable to directors, however, began to depart significantly from traditional principles of equity that required "no possibility" of conflict regarding corporate opportunities, and "no inquiry" into the actual terms of transactions if tainted by self-dealing.

[155] The directors of TransUnion, including Jerome W. Van Gorkom, were sued by the shareholders for failing to adequately research the corporation's value, before approving a sale price of $55 per share to the Marmon Group.

The Court held that to be a protected business judgment, "the directors of a corporation [must have] acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the company."

[153] Chancellor Chandler, confirming his previous opinions in Re Walt Disney and the dicta of Re Caremark, held that the directors of Citigroup could not be liable for failing to have a warning system in place to guard against potential losses from sub-prime mortgage debt.

Although there had been several indications of the significant risks, and Citigroup's practices along with its competitors were argued to have contributed to crashing the international economy, Chancellor Chandler held that "plaintiffs would ultimately have to prove bad faith conduct by the director defendants".

There was "a presumption that in making a business decision, the directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis in good faith and in the honest belief that the action was taken in the best interests of the company", even if they owed their jobs to the person being sued.

The tendency in Delaware, however, has remained to allow the board to play a role in restricting litigation, and therefore minimize the chances that it could be held accountable for basic breaches of duty.