Varieties of Arabic

[3] In terms of sociolinguistics, a major distinction exists between the formal standardized language, found mostly in writing or in prepared speech, and the widely diverging vernaculars, used for everyday speaking situations.

In other words, Arabic in its natural environment usually occurs in a situation of diglossia, which means that its native speakers often learn and use two linguistic forms substantially different from each other, the Modern Standard Arabic (often called MSA in English) as the official language and a local colloquial variety (called العامية, al-ʿāmmiyya in many Arab countries,[a] meaning "slang" or "colloquial"; or called الدارجة, ad-dārija, meaning "common or everyday language" in the Maghreb[7]), in different aspects of their lives.

While vernacular varieties differ substantially, fuṣḥa (فصحى), the formal register, is standardized and universally understood by those literate in Arabic.

Often, Arabic speakers can adjust their speech in a variety of ways according to the context and to their intentions—for example, to speak with people from different regions, to demonstrate their level of education or to draw on the authority of the spoken language.

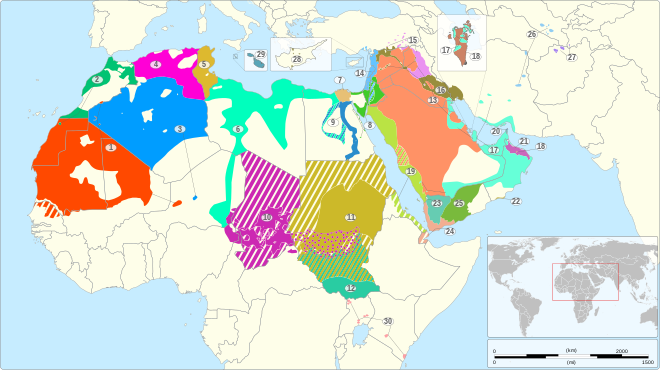

[citation needed] Arab dialectologists have now adopted a more detailed classification for modern variants of the language, which is divided into five major groups: Peninsular, Mesopotamian, Levantine, Egypto-Sudanic or Nile Valley (including Egyptian and Sudanese), and Maghrebi.

There can be a number of motives for changing one's speech: the formality of a situation, the need to communicate with people with different dialects, to get social approval, to differentiate oneself from the listener, when citing a written text to differentiate between personal and professional or general matters, to clarify a point, and to shift to a new topic.

For Jordanian women from Bedouin or rural background, it may be the urban dialects of the big cities, especially including the capital Amman.

For example, a woman on a TV program could appeal to the authority of the formal language by using elements of it in her speech in order to prevent other speakers from cutting her off.

[18] The change can be temporary, as when a group of speakers with substantially different Arabics communicate, or it can be permanent, as often happens when people from the countryside move to the city and adopt the more prestigious urban dialect, possibly over a couple of generations.

[20] Iraqi/Kuwaiti aku, Levantine fīh and North African kayn all evolve from Classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound different.

A basic distinction that cuts across the entire geography of the Arabic-speaking world is between sedentary and nomadic varieties (often misleadingly called Bedouin).

As regions were conquered, army camps were set up that eventually grew into cities, and settlement of the rural areas by nomadic Arabs gradually followed thereafter.

[specify] This has led to the suggestion, first articulated by Charles Ferguson, that a simplified koiné language developed in the army staging camps in Iraq, whence the remaining parts of the modern Arab world were conquered.

[citation needed] A number of cities in the Arabic world speak a "Bedouin" variety, which acquires prestige in that context.

[citation needed] The following example illustrates similarities and differences between the literary, standardized varieties, and major urban dialects of Arabic.

In the eleventh century, the medieval geographer al-Bakri records a text in an Arabic-based pidgin, probably one that was spoken in the region corresponding to modern Mauritania.

Immigrant speakers of Arabic often incorporate a significant amount of vocabulary from the host-country language in their speech, in a situation analogous to Spanglish in the United States.

There are two formal varieties, or اللغة الفصحى al-lugha(t) al-fuṣḥá, One of these, known in English as Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is used in contexts such as writing, broadcasting, interviewing, and speechmaking.

In Algeria, colloquial Maghrebi Arabic was taught as a separate subject under French colonization, and some textbooks exist.

Three scientific papers concluded, using various natural language processing techniques, that Levantine dialects (and especially Palestinian) were the closest colloquial varieties, in terms of lexical similarity, to Modern Standard Arabic: Harrat et al. (2015, comparing MSA to two Algerian dialects, Tunisian, Palestinian, and Syrian),[32] El-Haj et al. (2018, comparing MSA to Egyptian, Levantine, Gulf, and North African Arabic),[33] and Abu Kwaik et al. (2018, comparing MSA to Algerian, Tunisian, Palestinian, Syrian, Jordanian, and Egyptian).

[34] Sociolinguistics is the study of how language usage is affected by societal factors, e.g., cultural norms and contexts (see also pragmatics).

In the Arab world, religion transcends the boundaries of personal belief, functioning as a pervasive and influential force in every facet of life.

From birth, individuals are not only given a name but are also ascribed a place within a specific religious order: whether as Muslims, divided into Sunni or Shia, or as Christians, Druze, or Jews.

Even language itself is moulded by this religious framework, reflecting the collective identity and adjusting to the intricate balance of belief systems.

It speaks for the individual, often before they can express themselves, and thus, the interplay between faith and politics must be fully understood to grasp the complexities of the language and culture of the Arab world.

This dominance is reflected in the public sphere, where the colloquial language presented on television and in media is almost exclusively that of the Sunni community.

This socio-political dynamic exerts a profound influence on the evolution of language in Bahrain, steering its development in line with the interests and cultural practices of the Sunni minority.

This observation is drawn from a study conducted prior to the Iraq War and the mass emigration of Iraqi Christians in the early 21st century.

The Christian community in Baghdad is longstanding, and their dialect traces its roots to the sedentary vernacular of urban medieval Iraq.

By contrast, the typical Muslim dialect of the city is a more recent development, originating from Bedouin speech patterns.

-

1: Hassaniyya

-

9: Saidi Arabic

-

10: Chadian Arabic

-

11: Sudanese Arabic

-

12: Juba Arabic

-

13: Najdi Arabic

-

14: Levantine Arabic

-

17: Gulf Arabic

-

18: Baharna Arabic

-

19: Hijazi Arabic

-

20: Shihhi Arabic

-

21: Omani Arabic

-

22: Dhofari Arabic

-

23: Sanaani Arabic

-

25: Hadrami Arabic

-

26: Uzbeki Arabic

-

27: Bactrian Arabic

-

28: Cypriot Arabic

-

29: Maltese

-

30: Nubi

-

Sparsely populated area or no indigenous Arabic speakers

- Solid area fill: variety natively spoken by at least 25% of the population of that area or variety indigenous to that area only

- Hatched area fill: minority scattered over the area

- Dotted area fill: speakers of this variety are mixed with speakers of other Arabic varieties in the area

a-b : fuṣḥā end

c-d : colloquial ( ‘āmmiyya ) end

a-g-e and e-h-b : pure fuṣḥā

c-g-f and f-h-d : pure colloquial

e-g-f-h : overlap of fuṣḥā and colloquial

a-g-c and b-h-d : foreign ( dakhīl ) influence