Analogy of the divided line

It is written as a dialogue between Glaucon and Socrates, in which the latter further elaborates upon the immediately preceding analogy of the Sun at the former's request.

These affections are described in succession as corresponding to increasing levels of reality and truth from conjecture (εἰκασία) to belief (πίστις) to thought (διάνοια) and finally to understanding (νόησις).

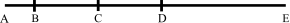

In The Republic (509d–510a), Socrates describes the divided line to Glaucon this way: Now take a line which has been cut into two unequal parts, and divide each of them again in the same proportion,[1] and suppose the two main divisions to answer, one to the visible and the other to the intelligible, and then compare the subdivisions in respect of their clearness and want of clearness, and you will find that the first section in the sphere of the visible consists of images.

These correspond to two kinds of knowledge, the illusion (eikasía) of our ordinary, everyday experience, and belief (πίστις pistis) about discrete physical objects which cast their shadows.

[5] Particularly, it is identified as the lower subsection of the visible segment and represents images, which Plato described as "first shadows, then reflections in water and in all compacted, smooth, and shiny materials".

Another variation posited by scholars such Yancey Dominick, explains that it is a way of understanding the originals that generate the objects that are considered as eikasia.

[8] According to some translations,[1] the segment CE, representing the intelligible world, is divided into the same ratio as AC, giving the subdivisions CD and DE (it can be readily verified that CD must have the same length as BC:[9] There are two subdivisions, in the lower of which the soul uses the figures given by the former division as images; the enquiry can only be hypothetical, and instead of going upwards to a principle descends to the other end; in the higher of the two, the soul passes out of hypotheses, and goes up to a principle which is above hypotheses, making no use of images as in the former case, but proceeding only in and through the ideas themselves (510b).

For example, he does not accept expertise about a subject, nor direct perception (see Theaetetus), nor true belief about the physical world (the Meno) as knowledge.

However, to ensure that the second level, the objective, physical world, is also unchanging, Plato, in the Republic, Book 4[18] introduces empirically derived[19][20][21] axiomatic restrictions that prohibit both motion and shifting perspectives.