Atlantis

[21] Plato introduced Atlantis in Timaeus, written in 360 BC: For it is related in our records how once upon a time your State stayed the course of a mighty host, which, starting from a distant point in the Atlantic ocean, was insolently advancing to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot.

For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent.

Poseidon carved the mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size.

But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.

Another passage from the commentary by Proclus on the Timaeus gives a description of the geography of Atlantis: That an island of such nature and size once existed is evident from what is said by certain authors who investigated the things around the outer sea.

[43]The theologian Joseph Barber Lightfoot (Apostolic Fathers, 1885, II, p. 84) noted on this passage: "Clement may possibly be referring to some known, but hardly accessible land, lying without the pillars of Hercules.

Francisco Lopez de Gomara was the first to state that Plato was referring to America, as did Francis Bacon and Alexander von Humboldt; Janus Joannes Bircherod said in 1663 orbe novo non-novo ("the New World is not new").

[21] Contemporary perceptions of Atlantis share roots with Mayanism, which can be traced to the beginning of the Modern Age, when European imaginations were fueled by their initial encounters with the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

In the middle and late nineteenth century, several renowned Mesoamerican scholars, starting with Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, and including Edward Herbert Thompson and Augustus Le Plongeon, formally proposed that Atlantis was somehow related to Mayan and Aztec culture.

The French scholar Brasseur de Bourbourg traveled extensively through Mesoamerica in the mid-1800s, and was renowned for his translations of Mayan texts, most notably the sacred book Popol Vuh, as well as a comprehensive history of the region.

Le Plongeon invented narratives, such as the kingdom of Mu saga, which romantically drew connections to him, his wife Alice, and Egyptian deities Osiris and Isis, as well as to Heinrich Schliemann, who had just discovered the ancient city of Troy from Homer's epic poetry (that had been described as merely mythical).

[60] He unintentionally promoted an alternative method of inquiry to history and science, and the idea that myths contain hidden information that opens them to "ingenious" interpretation by people who believe they have new or special insight.

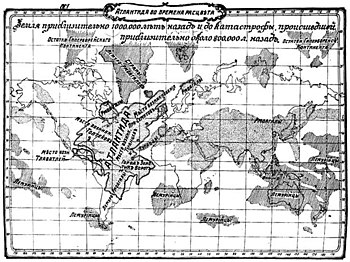

[54] In her book, Blavatsky reported that the civilization of Atlantis reached its peak between 1,000,000 and 900,000 years ago, but destroyed itself through internal warfare brought about by the dangerous use of psychic and supernatural powers of the inhabitants.

[62] Drawing on the ideas of Rudolf Steiner and Hanns Hörbiger, Egon Friedell started his book Kulturgeschichte des Altertums [de], and thus his historical analysis of antiquity, with the ancient culture of Atlantis.

In the dialogue, Critias says, referring to Socrates' hypothetical society: And when you were speaking yesterday about your city and citizens, the tale which I have just been repeating to you came into my mind, and I remarked with astonishment how, by some mysterious coincidence, you agreed in almost every particular with the narrative of Solon. ...

[84] The Thera eruption, dated to the seventeenth or sixteenth century BC, caused a large tsunami that some experts hypothesize devastated the Minoan civilization on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the story.

Others have noted that, before the sixth century BC, the mountains on either side of the Laconian Gulf were called the "Pillars of Hercules",[38][39] and they could be the geographical location being described in ancient reports upon which Plato was basing his story.

[102] In 2011, a team, working on a documentary for the National Geographic Channel,[103] led by Professor Richard Freund from the University of Hartford, claimed to have found possible evidence of Atlantis in southwestern Andalusia.

[104] The team identified its possible location within the marshlands of the Doñana National Park, in the area that once was the Lacus Ligustinus,[105] between the Huelva, Cádiz, and Seville provinces, and they speculated that Atlantis had been destroyed by a tsunami,[106] extrapolating results from a previous study by Spanish researchers, published four years earlier.

[108] A similar theory had previously been put forward by a German researcher, Rainer W. Kühne, that is based only on satellite imagery and places Atlantis in the Marismas de Hinojos, north of the city of Cádiz.

Silenus describes the Meropids, a race of men who grow to twice normal size, and inhabit two cities on the island of Meropis: Eusebes (Εὐσεβής, "Pious-town") and Machimos (Μάχιμος, "Fighting-town").

[125] It was followed in Russia by Velimir Khlebnikov's poem The Fall of Atlantis (Gibel' Atlantidy, 1912), which is set in a future rationalist dystopia that has discovered the secret of immortality and is so dedicated to progress that it has lost touch with the past.

Its three parts consist of a verse narrative of the life and training of an Atlantean wise one, followed by his Utopian moral teachings and then a psychic drama set in modern times in which a reincarnated child embodying the lost wisdom is reborn on earth.

[129] One response was the similarly entitled Argentinian Atlantida of Olegario Víctor Andrade (1881), which sees in "Enchanted Atlantis that Plato foresaw, a golden promise to the fruitful race" of Latins.

José Juan Tablada characterises its threat in his "De Atlántida" (1894) through the beguiling picture of the lost world populated by the underwater creatures of Classical myth, among whom is the Siren of its final stanza with her eye on the keel of the wandering vessel that in passing deflowers the sea's smooth mirror, launching into the night her amorous warbling and the dulcet lullaby of her treacherous voice!

[140] In the second, Mona, Queen of Lost Atlantis: An Idyllic Re-embodiment of Long Forgotten History (Los Angeles CA 1925) by James Logue Dryden (1840–1925), the story is told in a series of visions.

[143] A final example, Edward N. Beecher's The Lost Atlantis or The Great Deluge of All (Cleveland OH, 1898) is just a doggerel vehicle for its author's opinions: that the continent was the location of the Garden of Eden; that Darwin's theory of evolution is correct, as are Donnelly's views.

His 250-page The Fall of Atlantis (1938) records how a high priest, distressed by the prevailing degeneracy of the ruling classes, seeks to create an androgynous being from royal twins as a means to overcome this polarity.

[160] In the case of the Brussels fountain feature known as The Man of Atlantis (2003) by the Belgian sculptor Luk van Soom [nl], the 4-metre tall figure wearing a diving suit steps from a plinth into the spray.

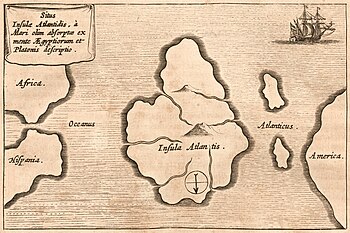

[164] On this he commented that he liked "landscapes that suggest prehistory", and this is borne out by the original conceptual drawing of the work that includes an inset map of the continent sited off the coast of Africa and at the straits into the Mediterranean.