Anarchism and violence

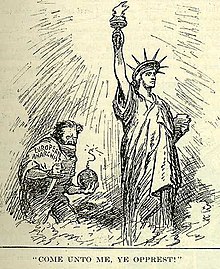

Leading late 19th century anarchists espoused propaganda by deed, or attentáts, and was associated with a number of incidents of political violence.

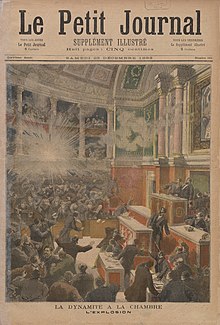

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by proponents of insurrectionary anarchism in the late 19th and early 20th century, including bombings and assassinations aimed at the State, the ruling class, and Church arsons targeting religious groups, even though propaganda of the deed also had non-violent applications.

[4] While revolutionary bombings and assassinations appeared as an indiscriminate call to violence to outsiders, anarchists saw "the idea of the propaganda by deed, or the attentat (attack), [as having] a very specific logic".

"The anarchist prophets of the 'propaganda by the deed' can argue all they want about the elevating and stimulating influence of terrorist acts on the masses," he wrote in 1911, "Theoretical considerations and political experience prove otherwise."

Vladimir Lenin largely agreed, viewing individual anarchist acts of terrorism as an ineffective substitute for coordinated action by disciplined cadres of the masses.

Berkman attempted propaganda by deed when he tried in 1892 to kill industrialist Henry Clay Frick following the deaths by shooting of several striking workers.

The dismemberment of the French socialist movement, into many groups and, following the suppression of the 1871 Paris Commune, the execution and exile of many communards to penal colonies, favored individualist political expression and acts.

[17] The anarchist Luigi Galleani, perhaps the most vocal proponent of propaganda by deed from the turn of the century through the end of the First World War, took undisguised pride in describing himself as a subversive, a revolutionary propagandist and advocate of the violent overthrow of established government and institutions through the use of 'direct action', i.e., bombings and assassinations.

[20] By all accounts, Galleani was an extremely effective speaker and advocate of his policy of violent action, attracting a number of devoted Italian-American anarchist followers who called themselves Galleanists.

Henry David Thoreau, though not a pacifist himself,[22] influenced both Leo Tolstoy and Mohandas Gandhi's advocacy of Nonviolent resistance through his work Civil Disobedience.

They were a predominantly peasant movement that set up hundreds of voluntary anarchist pacifist communes based on their interpretation of Christianity as requiring absolute pacifism and the rejection of all coercive authority.

"[24] "Gandhi's ideas were popularized in the West in books such as Richard Gregg's The Power of Nonviolence (1935), and Bart de Ligt's The Conquest of Violence (1937).

Not the bomb-in-the-pocket stuff, which is terrorism, whatever name it tries to dignify itself with, not the social-Darwinist economic 'libertarianism' of the far right; but anarchism, as prefigured in early Taoist thought, and expounded by Shelley and Kropotkin, Goldman and Goodman.

Anarchism's principal target is the authoritarian State (capitalist or socialist); its principle moral-practical theme is cooperation (solidarity, mutual aid).

Goldman herself didn't oppose tactics like assassination in her early career, but changed her views after she went to Russia, where she witnessed the violence of the Russian state and the Red Army.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued in favor of a non-violent revolution through a process of dual power in which libertarian socialist institutions would be established and form associations enabling the formation of an expanding network within the existing state-capitalist framework with the intention of eventually rendering both the state and the capitalist economy obsolete.

According to Gelderloos, pacifism as an ideology serves the interests of the state and is hopelessly caught up psychologically with the control schema of patriarchy and white supremacy.

Then Versailles seized the moment to attack and, in one horrifying week, executed roughly 20,000 Communards or suspected sympathizers, a number higher than those killed in the recent war or during Robespierre's 'Terror' of 1793–94.

Many of France's leading intellectuals and artists had participated in the Commune (Courbet was its quasi-minister of culture, Rimbaud and Pissarro were active propagandists) or were sympathetic to it.