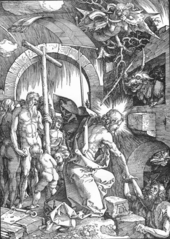

Harrowing of Hell

[2] The Catechism of the Catholic Church notes Ephesians 4:9, which states that "[Christ] descended into the lower parts of the earth", as also supporting this interpretation.

[1] As a subject in Christian art, it is also known as the Anastasis (Greek for "resurrection"), considered a creation of Byzantine culture and first appearing in the West in the early 8th century.

[10] The Greek wording in the Apostles' Creed is κατελθόντα εἰς τὰ κατώτατα (katelthonta eis ta katōtata), and in Latin is descendit ad inferos.

The Greek τὰ κατώτατα (ta katōtata, "the lowest") and the Latin inferos ("those below") may also be translated as "underworld", "netherworld", or "abode of the dead".

[14] The Harrowing of Hell was taught by theologians of the early church: St Melito of Sardis (died c. 180) in his Homily on the Passover and more explicitly in his Homily for Holy Saturday, Tertullian (A Treatise on the Soul, 55, though he himself disagrees with the idea), Hippolytus (Treatise on Christ and Anti-Christ), Origen (Against Celsus, 2:43), and, later, Ambrose (died 397) all wrote of the Harrowing of Hell.

The 6th-century sect called the Christolytes, as recorded by John of Damascus, believed that Jesus left his soul and body in Hell, and only rose with his divinity to Heaven.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Harrowing of Hades is celebrated annually on Holy and Great Saturday during the Vesperal Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil, as is normative for the Byzantine Rite.

Then, just before the Gospel reading, the liturgical colors are changed to white and the deacon performs a censing, and the priest strews laurel leaves around the church, symbolizing the broken gates of Hell; this is done in celebration of the harrowing of Hades then taking place, and in anticipation of Christ's imminent resurrection.

Traditionally, he is not shown holding them by the hands but by their wrists, to illustrate the theological teaching that mankind could not pull himself out of his Original sin, but that it could come about only by the work (energia) of God.

"[17] As the Catechism says, the word "Hell"—from the Norse, Hel; in Latin, infernus, infernum, inferni; in Greek, ᾍδης (Hades); in Hebrew, שאול (Sheol)—is used in Scripture and the Apostles' Creed to refer to the abode of all the dead, whether righteous or evil, unless or until they are admitted to Heaven (CCC 633).

For instance, Thomas Aquinas taught that Christ did not descend into the "Hell of the lost" in his essence, but only by the effect of his death, through which "he put them to shame for their unbelief and wickedness: but to them who were detained in Purgatory he gave hope of attaining to glory: while upon the holy Fathers detained in Hell solely on account of original sin, he shed the light of glory everlasting.

Many attempts were made following Luther's death to systematize his theology of the descensus, whether Christ descended in victory or humiliation.

Luther himself, when pressed to elaborate on the question of whether Christ descended to Hell in humiliation or victory responded, "It is enough to preach the article to the laypeople as they have learned to know it in the past from the stained glass and other sources.

"[21] "Anglican orthodoxy, without protest, has allowed high authorities to teach that there is an intermediate state, Hades, including both Gehenna and Paradise, but with an impassable gulf between the two.

Calvin's conclusion is that "If any persons have scruples about admitting this article into the Creed, it will soon be made plain how important it is to the sum of our redemption: if it is left out, much of the benefit of Christ’s death will be lost.

Joseph F. Smith, the sixth president of the Church, explained in what is now a canonized revelation, that when Christ died, "there were gathered together in one place an innumerable company of the spirits of the just, ... rejoicing together because the day of their deliverance was at hand.

[25] In the Latter-day Saint view, while Christ announced freedom from physical death to the just, he had another purpose in descending to Hell regarding the wicked.

[27] This concept goes hand-in-hand with the doctrine of baptism for the dead, which is based on the Latter-day Saint belief that those who choose to accept the gospel in the spirit world must still receive the saving ordinances in order to dwell in the kingdom of God.

This he declares is clear, beyond all doubt, that Jesus Christ descended in soul after his death into the regions below, and concludes with these words: Quis ergo nisi infidelis negaverit fuisse apud inferos Christum?

[34] The Harrowing of Hell was a major scene in traditional depictions of Christ's life avoided by John Milton due to his mortalist views.

[39] The richest, most circumstantial accounts of the Harrowing of Hell are found in medieval dramatic literature, such as the four great cycles of English Mystery plays which each devote a separate scene to depict it.

[43] The Catholic philologist and fantasy author J. R. R. Tolkien echoes the Harrowing of Hell theme in multiple places in The Silmarillion (1977) and The Lord of the Rings (1954–55).

[44] In Stephen Lawhead's novel Byzantium (1997), a young Irish monk is asked to explain Jesus Christ's life to a group of Vikings, who were particularly impressed with his "descent to the underworld" (Helreið).

[citation needed] Parallels in Jewish literature refer to legends of Enoch and Abraham's harrowings of the Underworld, unrelated to Christian themes.

These have been updated in Isaac Leib Peretz's short story "Neilah in Gehenna", in which a Jewish hazzan descends to Hell and uses his unique voice to bring about the repentance and liberation of the souls imprisoned there.