Anchiceratops

Sternberg, 1929 Anchiceratops (/ˌæŋkiˈsɛrətɒps/ ANG-kee-SERR-ə-tops) is an extinct genus of chasmosaurine ceratopsid dinosaur that lived approximately 72 to 71 million years ago during the latter part of the Cretaceous Period in what is now Alberta, Canada.

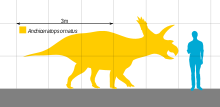

Anchiceratops was a medium-sized, heavily built, ground-dwelling, quadrupedal herbivore that could grow up to an estimated 4.3 metres (14 ft) long.

The first remains of Anchiceratops were discovered along the Red Deer River in the Canadian province of Alberta in 1912 by an expedition led by Barnum Brown.

The skulls are different with respect to their proportions (e.g. size of the supraorbital horn cores, the dimensions of the frill) which had led researchers to conclude that the disparity is ontogenetic.

[7] Frill fragments found in the early Maastrichtian Almond Formation of Wyoming in the United States resemble Anchiceratops.

[10] Anchiceratops remains were also recovered in terrestrial sediments from the St. Mary River Formation at the Scabby Butte locality in southwestern Alberta, however, the fossils cannot be referred to a specific species.

Like other ceratopsids, A. ornatus was a quadrupedal herbivore with three horns on its face, a parrot-like beak, and a long frill extending from the back of its head.

[1] In 2010 Gregory S. Paul, on the assumption that specimen NMC 8547 represented Anchiceratops, estimated its length at 4.3 metres, its weight at 1.2 tonnes.

[15] In the same year Lawrence Lambe assigned this genus to a new taxon that he erected, "eoceratopsinae", which included "Eoceratops" (now Chasmosaurus), "Diceratops" (now Nedoceratops) and Triceratops.

[14] Mallon's study of 2012 concluded however, that Anchiceratops was more closely related to Chasmosaurus than to Triceratops, suggesting that this genus was less derived than previously thought.

Sternberg had originally designated a smaller skull as the type specimen for a new species Anchiceratops longirostris, because of its size and its horns which are significantly more slender and point forward instead of upward.

[13] Anchiceratops is rare compared to other ceratopsians in the area, and usually found near marine sediments, in both the Horseshoe Canyon and Dinosaur Park Formations.

Flowering plants were increasingly common but still rare compared to the conifers, cycads and ferns which probably made up the majority of ceratopsian diets.

The long snout would have allowed the animal to cross deeper swamps walking, catching breath on the water's surface and the heavy frill would have acted as a counterbalance to help point the beak upwards.

[10] Later paleontologists tended to reject this notion, emphasizing that dinosaurs in general were land animals, but in 2012 Mallon again suggested a semi-aquatic lifestyle, like a modern hippopotamus, at least for specimen NMC 8547.

Several possible explanations were given: a decreased competition by related species; less habitat fragmentation by the recession of the Western Interior Seaway; and a more generalist lifestyle.

[27][28] Anchiceratops shared its paleoenvironment with other dinosaurs, such as maniraptorans (Epichirostenotes curriei), ornithomimids (Ornithomimus edmontonicus), pachycephalosaurids (Sphaerotholus edmontonensis), hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus regalis), ceratopsians (Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis), and tyrannosaurids (Albertosaurus sarcophagus), which were apex predators.

Reptiles such as turtles and crocodilians are rare in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, and this was thought to reflect the relatively cool climate which prevailed at the time.

A study by Quinney et al. (2013) however, showed that the decline in turtle diversity, which was previously attributed to climate, coincided instead with changes in soil drainage conditions, and was limited by aridity, landscape instability, and migratory barriers.

[30] Vertebrate trace fossils from this region included the tracks of theropods, ceratopsians and ornithopods, which provide evidence that these animals were also present.