Lycia

Written records began to be inscribed in stone in the Lycian language after Lycia's involuntary incorporation into the Achaemenid Empire in the Iron Age.

The next ridge to the east is Akdağlari, 'the White Mountains', about 150 km (93 mi) long, with a high point at Uyluktepe, "Uyluk Peak", of 3,024 m (9,921 ft).

The Aedesa once drained the plain through a chasm to the east, but now flows entirely through pipelines covering the same route, but emptying into the water supplies of Arycanda and Arif.

Within the park on the slopes of Mount Olympus is a U-shaped outcrop, Yanartaş, above Cirali, from which methane gas, naturally perpetually escaping from below through the rocks, feeds eternal flames.

Through the cul-de-sac between Baydağlari and Tahtalidağlari, the Alakir Çay ('Alakir River'), the ancient Limyra, flows to the south trickling from the broad valley under superhighway D400 near downtown Kumluca across a barrier beach into the Mediterranean.

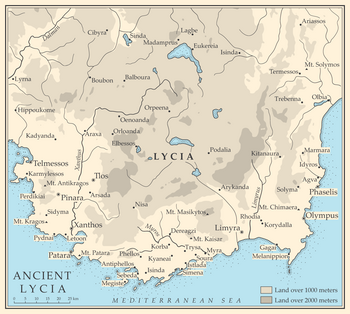

The principal cities of ancient Lycia were Xanthos, Patara, Myra, Pinara, Tlos and Olympos (each entitled to three votes in the Lycian League) and Phaselis.

Although the 2nd-century BC dialogue Erōtes found the cities of Lycia "interesting more for their history than for their monuments, since they have retained none of their former splendor," many relics of the Lycians remain visible today.

Letoon, an important center in Hellenic times of worship for the goddess Leto and her twin children, Apollo and Artemis, and nearby Xanthos, ancient capital of Lycia, constitute a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This coast features rocky or sandy beaches at the bases of cliffs and settlements in protected coves that cater to the yachting industry.

Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, resolved to complete the conquest of Anatolia as a prelude to operations further west, to be carried out by his successors.

He assigned the task to Harpagus, a Median general, who proceeded to subdue the various states of Anatolia, one by one, some by convincing them to submit, others through military action.

Arriving at the southern coast of Anatolia in 546 BC, the army of Harpagus encountered no problem with the Carians and their immediate Greek neighbors and alien populations, who submitted peacefully.

Then, after taking an oath not to surrender, they died to a man fighting the Persians, foreshadowing and perhaps setting an example for Spartan conduct at the Battle of Thermopylae a few generations later.

Herodotus also says or implies that 80 Xanthian families were away at the time, perhaps with the herd animals in alpine summer pastures (pure speculation), but helped repopulate the place.

[22] The main evidence against the Harpagid Theory (as Keen calls it) is the reconstruction of the name of the Xanthian Obelisk's deceased as Lycian Kheriga, Greek Gergis (Nereid Monument), a king reigning approximately 440–410 BC, over a century later than the conqueror of Lycia.

The reason for this tolerance after such a determined initial resistance is that the Iranians were utilizing another method of control: the placement of aristocratic Persian families in a region to exercise putative home rule.

[32] The first dynast is believed to be the person mentioned in the last line of the Greek epigram inscribed on the Xanthian Obelisk, which says "this monument has brought glory to the family (genos) of ka[]ika," which has a letter missing.

[33] Herodotus mentioned that the leader of the Lycian fleet under Xerxes in the Second Persian War of 480 BC was Kuberniskos Sika, previously interpreted as "Cyberniscus, the son of Sicas," two non-Lycian names.

Keen suggests that Darius I created the kingship on reorganizing the satrapies in 525, and that on the intestate death of Kubernis in battle, the Persians chose another relative named Kheziga, who was the father of Kuprlli.

[50] Although many of the first coins in Antiquity illustrated the images of various gods, the first portraiture of actual rulers appears with the coinage of Lycia in the late 5th century BC.

[52] The Achaemenids had been the first to illustrate the person of their king or a hero in a stereotypical undifferentiated manner, showing a bust or the full body, but never an actual portrait, on their Sigloi and Daric coinage from circa 500 BC.

Ptolemy II Philadelphos (ruled 285–246 BC), who supported the Limyrans of Lycia when they were threatened by the Galatians (a Celtic tribe that had invaded Asia Minor).

When Roman envoys went to the city he begged them not to ravage his lands as he was a friend of Rome and promised a paltry sum of money, fifteen talents.

Moagetes and his friends went to meet Manlius dressed in humble clothing, bewailing the weakness of his town and begging to accept the fifteen talents.

The Lycian League (Lykiakon systema in Strabo's Greek transliterated, a "standing together") is first known from two inscriptions of the early 2nd century BC in which it honors two citizens.

It was slavery, rather that just political oppression: "they, their wives and children were the victims of violence; their oppressors vented their rage on their persons and their backs, their good name was besmirched and dishonoured, their condition rendered detestable in order that their tyrants might openly assert a legal right over them and reduce them to the status of slaves bought with money.. the senate gave them a letter to and to the Rhodians that ...it was not the pleasure of the senate that either the Lycians or any other men born free should be handed over as slaves to the Rhodians or any one else.

[63] In 169 BC, during the Third Macedonian War, the relationship between Rome and Rhodes became strained and the Roman senate issued a decree which gave the Carians and the Lycians their freedom.

The first article stipulated "Friendship, alliance and peace both by land and sea in perpetuity "Let the Lycians observe the power and preeminence of the Romans as is proper in all circumstances."

"[75] In an inscription found at Perge which has been dated to late 46/early 45 BC the Lycians, who described themselves as 'faithful allies’, praised Claudius for freeing them from disturbances, lawlessness and brigandage and for the restoration of the ancestral laws.

Subsequently, Lycus of Athens (son of Pandion II), who was driven into exile by his brother, King Aegeus, settled in Milyas among the Termilae.