Vandalic War

After Geiseric's death in 477, relations with the Eastern Roman Empire were normalized, although tensions flared up occasionally due to the Vandals' adherence to Arianism and their persecution of the Nicene native population.

Imperial control scarcely reached beyond the old Vandal kingdom, however, and the Mauri tribes of the interior, unwilling to accept Roman rule, soon rose up in rebellion.

In the course of the gradual decline and dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in the early 5th century, the Germanic tribe of the Vandals, allied with the Alans, had established themselves in the Iberian Peninsula.

[4][5] Although the Vandals now gained control of the lucrative African grain trade with Italy, they also launched raids on the coasts of the Mediterranean that ranged as far as the Aegean Sea and culminated in their sack of Rome itself in 455, which allegedly lasted for two weeks.

Taking advantage of the chaos that followed Valentinian's death in 455, Geiseric then regained control—albeit rather tenuous—of the Mauretanian provinces, and with his fleet took over Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic Islands.

[8][9] In the aftermath of this disaster, and following further Vandal raids against the shores of Greece, the eastern emperor Zeno (r. 474–491) concluded a "perpetual peace" with Geiseric (474/476).

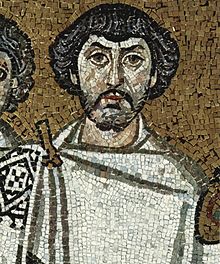

Himself a descendant of Valentinian III, Hilderic re-aligned his kingdom and brought it closer to the Roman Empire: according to the account of Procopius (The Vandalic War, I.9) he was an unwarlike, amiable person, who ceased the persecution of the Chalcedonians, exchanged gifts and embassies with Justinian I (r. 527–565) even before the latter's rise to the throne, and even replaced his image in his coins with that of the emperor.

[11][15] However, Hilderic's pro-Roman policies, coupled with a defeat suffered against the Mauri in Byzacena, led to opposition among the Vandal nobility, which resulted in his overthrow and imprisonment in 530 by his cousin, Gelimer (r. 530–534).

[20][21] Soon after his seizure of power, Gelimer's domestic position began to deteriorate, as he persecuted his political enemies among the Vandal nobility, confiscating their property and executing many of them.

[22][23] Although Procopius' narrative makes both uprisings seem coincidental, Ian Hughes points out the fact that both rebellions broke out shortly before the commencement of the Roman expedition against the Vandals, and that both Godas and Pudentius immediately asked for assistance from Justinian, as evidence of an active diplomatic involvement by the Emperor in their preparation.

Gelimer also chose to ignore the revolt in Tripolitania for the moment, as it was both a lesser threat and more remote, while his lack of manpower constrained him to await Tzazon's return from Sardinia before undertaking further campaigns.

[28][29][30] Justinian selected one of his most trusted and talented generals, Belisarius, who had recently distinguished himself against the Persians[citation needed] and in the suppression of the Nika riots, to lead the expedition.

As Ian Hughes points out, Belisarius was also eminently suited for this appointment for two other reasons: he was a native Latin-speaker, and was solicitous of the welfare of the local population, keeping a tight leash on his troops.

The eunuch Solomon was chosen as Belisarius' chief of staff (domesticus) and the former praetorian prefect Archelaus was placed in charge of the army's provisioning, while Rufinus the Thracian and Aïgan the Hun led the cavalry.

The latter informed Procopius that not only were the Vandals unaware of Belisarius' sailing, but that Gelimer, who had just dispatched Tzazon's expedition to Sardinia, was away from Carthage at the small inland town of Hermione.

Thus on the next day of the landing, when some of his men stole some fruit from a local orchard, he severely punished them, and assembled the army and exhorted them to maintain discipline and restraint towards the native population, lest they abandon their Roman sympathies and go over to the Vandals.

[27][49] Deprived of his best troops, which were with Tzazon, Gelimer contented himself with shadowing the northward march of the Roman army, all the while preparing a decisive engagement before Carthage, at a place called Ad Decimum ("at the tenth [milepost]") where he had ordered Ammatas to bring his forces.

While Belisarius himself took possession of the royal palace, seated himself on the king's throne, and consumed the dinner which Gelimer had confidently ordered to be ready for his own victorious return, the fleet entered the Lake of Tunis and the army was billeted throughout the city.

Belisarius dispatched Solomon to Constantinople to bear the emperor news of the victory, but expecting an imminent re-appearance of Gelimer with his army, he lost no time in repairing the largely ruined walls of the city and rendering it capable of sustaining a siege.

By distributing money he had managed to cement the loyalty of the locals to his cause, and sent messages recalling Tzazon and his men from Sardinia, where they had been successful in re-establishing Vandal authority and killing Godas.

[54][57] During this period, messengers from Tzazon, sent to announce his recovery of Sardinia, sailed into Carthage unaware that the city had fallen and were taken captive, followed shortly after by Gelimer's envoys to Theudis, who had reached Spain after the news of the Roman successes had arrived there and hence failed to secure an alliance.

Indeed, Vandal agents had already made contact with them, but Belisarius managed to maintain their allegiance—at least for the moment—by making a solemn promise that after the final victory they would be richly rewarded and allowed to return to their homes.

Gelimer, seeing that all was lost, fled with a few attendants into the wilds of Numidia, whereupon the remaining Vandals gave up all thoughts of resistance and abandoned their camp to be plundered by the Romans.

[63] As Bury comments, the expedition's fate might have been quite different "if Belisarius had been opposed to a commander of some ability and experience in warfare", and points out that Procopius himself "expresses amazement at the issue of the war, and does not hesitate to regard it not as a feat of superior strategy but as a paradox of fortune".

The Romans halted to mourn their leader, allowing Gelimer to escape, first to Hippo Regius and from there to the city of Medeus on Mount Papua, on whose Mauri inhabitants he could rely.

[65] Belisarius was also named consul ordinarius for the year 535, allowing him to celebrate a second triumphal procession, being carried through the streets seated on his consular curule chair, held aloft by Vandal warriors, distributing largesse to the populace from his share of the war booty.

[78] Almost from the start, an extensive fortification programme was also initiated, including the construction of city walls as well as smaller forts to protect the countryside, whose remnants are still among the most prominent archaeological remains in the region.

The first imperial governor, Belisarius' former domesticus Solomon, who combined the offices of both magister militum and praetorian prefect, was able to score successes against them and strengthen Roman rule in Africa, but his work was interrupted by a widespread military mutiny in 536.

In his later work, the Secret History, composed several years after the events of the Vandal War, Procopius provides a critical and unvarnished assessment of Emperor Justinian's administration of the newly acquired province.

This controversial and rather scathing account of Justinian's reign reveals not only the military triumphs but also the complexities of governing the territory, including the contentious issues, corruption, and discontent that accompanied the post-war period.