Andrew Amos (lawyer)

[1] Amos was called to the bar by the Middle Temple and joined the Midland circuit, where he soon acquired a reputation for rare legal learning, and his personal character secured him a large arbitration practice.

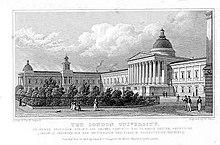

Within the next eight years Amos became auditor of Trinity College, Cambridge; recorder of Oxford, Nottingham, and Banbury; fellow of the new University of London; and criminal law commissioner.

In 1837 Amos was appointed "fourth member" of the council of the Governor-General of India, in succession to Lord Macaulay, and for the next five years he took an active part in rendering the code sketched out by his predecessor practically workable.

At the close of Amos's term in India, he was forced into an official controversy with Lord Ellenborough, the Governor-General, as to the right of the "fourth member" to sit at all meetings of the council in a political as well as a legislative capacity.

Amos reproduced and criticised the proceedings at some of these trials, and denounced the state of things as one "to which no British colony had hitherto afforded a parallel, private vengeance arrogating the functions of public law; murder justified in a British court of judicature, on the plea of exasperation commencing years before the sanguinary act; the spirit of monopoly raging in all the terrors of power, in all the force of organisation, in all the insolence of impunity".

In 1825 Amos edited for the syndics of the University of Cambridge John Fortescue's De Laudibus Legum Angliæ, appending the English translation of 1775, and original notes, or rather dissertations, by himself.

He had shared with Samuel March Phillipps the task of bringing out a treatise on the law of evidence, and had taken upon himself the whole charge of the preparation of the eighth edition, published in 1838; when, in 1837, he went to India, he had not quite finished the work.

He published various introductory lectures on diverse parts of the laws of England,[12] and pamphlets on various subjects, such as the constitution of the new county courts, the expediency of admitting the testimony of parties to suits,[13] and other measures of legal reform.

Amos's political and philosophical convictions were those of an advanced liberalism qualified by a profound knowledge of the constitutional development of the country and of the sole conditions under which the public improvements for which he longed and lived could alone be hopefully attempted.