Aniconism in Christianity

Those in the faith have generally had an active tradition of making artwork and Christian media; depicting God, Jesus, The Holy Spirit, religious figures including saints and prophets, and other aspects of theology like The Trinity and Manus Dei.

While some Anglicans (typically of the Low-Church variety) maintain the aniconism of the English Reformation, articulated in the religious injunctions of Edward VI[8] and Elizabeth I,[9] as well as the Homily against the Peril of Idolatry and the Superfluous Decking of Churches,[10] other Anglicans, influenced by the Oxford Movement and later Anglo-Catholicism, have introduced the devotional use of images back into their churches.

Several voices in early Christianity expressed "grave reservations about the dangers of images",[11] though contextualizing these remarks has often been the source of fierce controversy, as the same texts were brought out at intervals in succeeding centuries.

No literary statement from the period prior to the year 300 would make one suspect the existence of any Christian images other than the most laconic and hieroglyphic of symbols.

The Catacombs of Rome contain the earliest images, mostly painted, but also including reliefs carved on sarcophagi, dating from the end of the 2nd century onwards.

[15] The traditional Protestant position on the history of images in places of worship however is expressed by Philip Schaff, who claimed that: Yet previous to the time of Constantine we find no trace of an image of Christ properly speaking except among the Gnostic Carpocratians and in the case of the heathen emperor Alexander Severus who adorned his domestic chapel as a sort of pantheistic Pantheon with representatives of all religions.

The above mentioned idea of the uncomely personal appearance of Jesus the entire silence of the Gospels about it and the Old Testament prohibition of images restrained the church from making either pictures or statues of Christ until the Nicene age when a great reaction in this respect took place though not without energetic and long continued opposition.

[20] Jocelyn Toynbee agrees: "In two-dimensional, applied art of this kind there was never any danger of idolatry in the sense of actual worship of cult-images and votive pictures".

At the Spanish non-ecumenical Synod of Elvira (c. 305) bishops concluded, "Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and adoration", if understood this way, it's the earliest such prohibition known.

[23] Eusebius (died 339) wrote a letter to Constantia (Emperor Constantine's sister) saying "To depict purely the human form of Christ before its transformation, on the other hand, is to break the commandment of God and to fall into pagan error";[24] though this did not stop her decorating her mausoleum with such images.

By the end of the century Bishop Epiphanius of Salamis (died 403) "seems to have been the first cleric to have taken up the matter of Christian religious images as a major issue".

Irenaeus, (c. 130–202) in his Against Heresies (1:25–26) says scornfully of the Gnostic Carpocratians, "They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them.

[36] The period after the reign of Justinian (527–565) evidently saw a huge increase in the use of images, both in volume and quality, and a gathering aniconic reaction.

[40] It is this period that the attribution to individual images of the potential to achieve, channel or display various forms of spiritual grace or divine power becomes a regular motif in literature.

[44] In the 6th century Julian of Atramytion objected to sculpture, but not paintings, which is effectively the Orthodox position to the present day, except for small works.

There has been much scholarly discussion over the possible influence on the Iconoclasts of the aniconism in Islam, the century-old religion which had inflicted devastating defeats on Byzantium in the decades preceding.

[48] Indeed, the final cessation of the iconoclast controversy and the permanent use of images in the Orthodox Church is celebrated annually during Great Lent during the Feast of Orthodoxy.

[49] In his travels through the Auvergne between 1007 and 1020 the cleric Bernard of Angers was initially disapproving of the large crucifixes with a sculpted three-dimensional corpus, and other religious statues that he saw, but he came to accept them.

[50] The depiction of God the Father in art long remained unacceptable; he was typically only shown with the features of Jesus, which had become fairly standardized by the 6th century, in scenes such as the Garden of Eden.

On the other hand, icons have a slightly different theological position in Orthodoxy and play a more significant part in religious life than in Roman Catholicism, let alone the Protestant churches.

[62] The altarpiece in St. Peter und Paul in Weimar exemplified the doctrine of the communion of saints by showing Luther and Cranach "alongside John the Baptist at the foot of the cross".

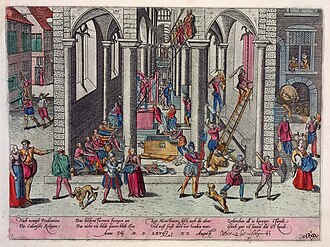

On the other hand, at the time of the Reformation, Calvinists preached in violent terms the rejection of what they perceived as idolatrous Catholic practices such as religious pictures, statues, or relics of saints, as well as against the Lutheran retention of sacred art.

During this time, early Anglicanism, falling with the broader Reformed tradition, also removed most religious images and symbols from churches and discouraged their private use.

Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558–1603), the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, was one of many Anglicans to exhibit somewhat contradictory attitudes, both ordering a crucifix for her chapel when they were against a law she had approved, and objecting forcefully when the Dean of St Paul's put in the royal pew a service book with "cuts resembling angels and saints, nay, grosser absurdities, pictures resembling the Holy Trinity".

Lutheran churches continue to be ornate, with respect to sacred art:[72] Lutheran places of worship contain images and sculptures not only of Christ but also of biblical and occasionally of other saints as well as prominent decorated pulpits due to the importance of preaching, stained glass, ornate furniture, magnificent examples of traditional and modern architecture, carved or otherwise embellished altar pieces, and liberal use of candles on the altar and elsewhere.

[72]Calvinist aniconism, especially in printed material, and stained glass, can generally be said to have weakened in force, although the range and context of images used are much more restricted than in Catholicism, Lutheranism, or parts of Anglicanism, the latter of which also incorporated many high church practices after the Oxford Movement.

[74][75] Bob Jones University, a standard bearer for Protestant Fundamentalism, has a major collection of Baroque old master Catholic altarpieces proclaiming the Counter-Reformation message, though these are in a gallery, rather than in a church.

[76] The Amish and some other Mennonite groups continue to avoid photographs or any depictions of people; their children's dolls usually have blank faces.

[80] In his 29 October 1997 general audience, Pope John Paul II reiterated the statement of Lumen gentium, 67 that: "the veneration of images of Christ, the Blessed Virgin and the saints, be religiously observed".

[5] In his 6 May 2009 general audience Pope Benedict XVI referred to the reasoning used by John of Damascus who wrote: "In other ages God had not been represented in images, being incorporate and faceless.