Fisherian runaway

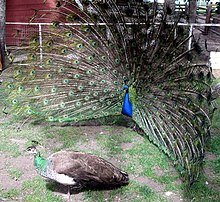

Extreme and (seemingly) maladaptive sexual dimorphism represented a paradox for evolutionary biologists from Charles Darwin's time up to the modern synthesis.

Darwin attempted to resolve the paradox by assuming heredity for both the preference and the ornament, and supposed an "aesthetic sense" in higher animals, leading to powerful selection of both characteristics in subsequent generations.

[3] When Wallace stated that animals show no sexual preference in his 1915 paper, The evolution of sexual preference, Fisher publicly disagreed:[7] The objection raised by Wallace ... that animals do not show any preference for their mates on account of their beauty, and in particular that female birds do not choose the males with the finest plumage, always seemed to the writer a weak one; partly from our necessary ignorance of the motives from which wild animals choose between a number of suitors; partly because there remains no satisfactory explanation either of the remarkable secondary sexual characters themselves, or of their careful display in love-dances, or of the evident interest aroused by these antics in the female; and partly also because this objection is apparently associated with the doctrine put forward by Sir Alfred Wallace in the same book, that the artistic faculties in man belong to his "spiritual nature", and therefore have come to him independently of his "animal nature" produced by natural selection.Fisher, in the foundational 1930 book, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection,[8] first outlined a model by which runaway inter-sexual selection could lead to sexually dimorphic male ornamentation based upon female choice and a preference for "attractive" but otherwise non-adaptive traits in male mates.

[7][8] Fisher outlined two fundamental conditions that must be fulfilled for the Fisherian runaway mechanism to lead to the evolution of extreme ornamentation: Fisher argued in his 1915 paper, "The evolution of sexual preference", that the type of female preference necessary for Fisherian runaway could be initiated without any understanding or appreciation for beauty.

[7] Fisher suggested that any visible features that indicate fitness, that are not themselves adaptive, that draw attention, and that vary in their appearance amongst the population of males so that the females can easily compare them, would be enough to initiate Fisherian runaway.

[7][1][2][10][11][12] Fisherian runaway assumes that sexual preference in females and ornamentation in males are both genetically variable (heritable).

Certain remarkable consequences do, however, follow ... in a species in which the preferences of ... the female, have a great influence on the number of offspring left by individual males.

— R. A. Fisher (1930)[8]Over time a positive feedback mechanism, one that involves a loop in which an increase in a quantity causes a further increase in the same quantity, will see more exaggerated sons and choosier daughters being produced with each successive generation; resulting in the runaway selection for the further exaggeration of both the ornament and the preference (until the costs for producing the ornament outweigh the reproductive benefit of possessing it).

Indicator hypotheses suggest that females choose desirably ornamented males because the cost of producing the desirable ornaments is indicative of good genes by way of the individual's vigour; for instance, the handicap principle proposes that females distinguish the best males by the measurable cost of certain visible features which have no other purpose, by analogy with a handicap race, in which the best horses carry the largest weights.