Anna Chertkova

[4] Anna Diterikhs was born into a family of professional military officers, married Vladimir Chertkov, an important publisher and public figure in the Russian government's opposition, was a close friend of Leo Tolstoy, and was known to her contemporaries as an active propagandist of Tolstoyan movement and vegetarianism.

She worked actively in the publishing company "Posrednik" and in the popular magazines of her time "Svobodnoye slovo" and "Listki svobodnogo slova".

In the early 1860s, Anna's family lived on the Volga River in a two-story wooden house with a mezzanine and a front garden in the town of Dubovka.

In the family, the girl was called Galya, not Anna, according to the order introduced by her maternal grandfather, General Osip Musnitsky, according to her memoirs, half-Polish, half-Lithuanian.

[6] Her mother was a deeply religious person, a firm supporter of Orthodoxy, while her father, who lived for a long time in the Caucasus, was interested in Islam as well as Christian sects: the studies of the Molokans and Dukhobors.

[3] It is reported by the Russian religious philosopher Nikolai Lossky that Anna Dieterichs used to work for some time as a teacher in a private female secondary educational institution in St. Petersburg, the Gymnasium of M. N. Stoyunina, where her younger sisters Olga and Maria were studying.

[10] Since 1885 Diterikhs began to participate in the work of the publishing house "Posrednik", where she was introduced by the public figure and publicist Pavel Biryukov.

[1] "Very painful and fragile, acutely experiencing every new impression, demanding and serious, A. K. Diterikhs was attracted to people and soon became a necessary worker in the new publishing house", - wrote about her Mikhail Muratov.

There were 30-40 people living in the house at the same time: Russians, Latvians, Estonians, Englishmen, who had different beliefs: there were Tolstoyans, social democrats, socialist-revolutionaries: "They were all doing something, working, and life was full and interesting.

[17] Anna Chertkova was seriously ill. Tolstoy admired her resilience and considered her one of those women for whom "the highest and living ideal is the coming of the Kingdom of God".

Yaroshenko's biographer, the chief researcher of his Memorial Museum Irina Polenova wrote that Chertkova also became a comic figure in the artist's graphics.

In the preface, Chertkova noted that some of the published texts actually belonged to free Christians, while others were "intended to satisfy their needs" for "spiritual songs" that corresponded to their "understanding of life"; thus, many of the texts were actually written by Russian poets such as Alexey Tolstoy, Alexander Pushkin and Alexey Khomyakov, and the melodies were taken from Russian folklore or works by well-known Western composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Frederic Chopin; the songs were published in a two-handed version for voice and clavichord).

[3][33][Note 6] Leo Tolstoy's secretary, Valentin Bulgakov, described the songs in the collections as "monotonous and dull," in which "even the calls for brotherhood and freedom sounded in a mournful minor key.

"Her "crowning" works were an aria from Christoph Willibald Gluck's "Iphigenia" and a song to words by Alfred Tennyson, translated by Aleksey Pleshcheyev, "Pale Arms Crossed on the Chest",[34] which she herself set to Beethoven.

According to his letters and personal memories of him" (1913, in this article Chertkova refuts the widespread opinion that Leo Tolstoy was prejudiced against Orthodoxy and therefore made no attempt to seriously familiarize himself with the writings of the Church Fathers)[36] and "Reflection of the thinking process in the 'Diary of Youth'" (1917).

[42] In the original text of her husband's biography, which Anna wrote together with Alexei Sergeenko, it is said:After becoming Chertkov's wife, Anna Konstantinovna, in spite of her fragile health, which often developed into acute illnesses, always participated with her heart and soul in all his activities and projects, supported her husband in his sometimes very difficult circumstances, and usually served as a center of inspiration and energy for the circle of collaborators and assistants that formed around them.

[7] The Russian State Archive of Literature and Art has Leo Tolstoy's signed review: "Anna Konstantinovna and Vladimir Grigorievich Chertkovy are my closest friends, and I not only always approve of all their activities concerning me and my works, but they also arouse in me the most sincere and deepest gratitude.

[54] He believed that Anna was the opposite of her husband: "Softness and even almost weakness of character, hardness of will, cordiality, modesty, sensitivity, attentive sympathy for the interests, sorrows and needs of neighbors, warm hospitality, a lively feminine curiosity about everything leading beyond the limits of the 'Tolstoyan' horizon".

Bulgakov noted that if the surrounding people were afraid of Vladimir Chertkov, his wife was loved by everyone, with whom she established "simple, trusting, friendly relations".

Bulgakov described its significance as the ability to "introduce the uncertain, weighty scope of his [Vladimir Chertkov's] heavy character into a more or less acceptable, disciplining framework, and also to facilitate access to him for other people - both those who lived with him under the same roof and those who appeared in his house for the first time".

I sit bent over on a wooden chair, she looks at me coldly... Later I heard about Anna Konstantinovna Chertkova from people who knew her better than I did, as a dry, calculating, even somewhat exploitative person with those around her... she was a musician, but could not write notes....

[71] The cultural historian Vladimir Porudominsky saw the reflection of several real women in the figure depicted in the painting: Maria Nevrotina - the artist's wife, a student of the first Bestuzhev courses; Nadezhda Stasova, a friend of the artist, a public figure, the sister of the music and art critic Vladimir Stasov, the wife of Yaroshenko's brother Vasily; Elisabeth Schlitter, a lawyer by training, a graduate of the University of Bern; and, above all, Anna Dieterichs, whom he considered the prototype of the heroine of the painting.

In Porudominsky's opinion, the artist, while working on the painting, gradually eliminated the likeness of his heroine to Dieterichs, thus achieving the transformation of the prototype into a type.

Soviet art historian Vladimir Porudominsky wrote that the painting's heroine "turned out to be a beautiful lady with exquisitely correct features (expressing less her or the artist's suffering than the desire to make them 'touching'), with thin, graceful hands that she deliberately shows...".

[77] [75] Contemporaries who knew Anna Chertkova perceived the painting "In a Warm Land" as a traditional portrait (although, according to Porudominsky, it contains a more complex plot).

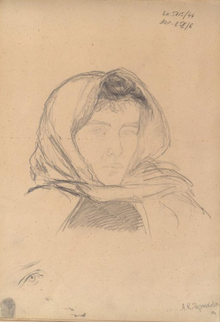

31 × 19 cm, Leo Tolstoy State Museum, Moscow, inventory АИЖ-396) and "Portrait of Anna Konstantinovna Chertkova" (1890, canvas, oil.

Art historian Irina Nikonova, in her monograph on the work of Mikhail Nesterov, insisted that these portraits were not an expression of his worldview, but a consequence of the artist's desire to capture close and beloved people.

The canvas gives a panorama of the Russian people, there are representatives of all estates of the realm and social classes, from the tsar to a fool and a blind soldier, in this crowd were depicted Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Solovyov.

[3] Nadezhda Zaitseva emphasized that in this painting Nesterov portrayed Anna Chertkova as a full-fledged character, a person searching for her God and ideals.

[84] On another page of the same album by Vladimir Chertkov are "Two Sketches of a Portrait of A. K. Chertkova" (date unknown, paper, pencil, 23 × 33 cm, inventory АИГ-858/8).