Aberration (astronomy)

It was first observed in the late 1600s by astronomers searching for stellar parallax in order to confirm the heliocentric model of the Solar System.

The aberration of light, together with Lorentz's elaboration of Maxwell's electrodynamics, the moving magnet and conductor problem, the negative aether drift experiments, as well as the Fizeau experiment, led Albert Einstein to develop the theory of special relativity in 1905, which presents a general form of the equation for aberration in terms of such theory.

At the time of the March equinox, Earth's orbit carries the observer in a southwards direction, and the star's apparent declination is therefore displaced to the south by an angle of

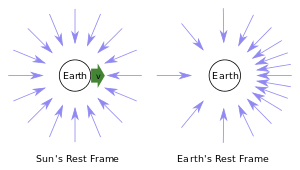

[13] In about 200 million years, the Sun circles the galactic center, whose measured location is near right ascension (α = 266.4°) and declination (δ = −29.0°).

[16]: 1 [12]: 1 Recently, highly precise astrometry of extragalactic objects using both Very Long Baseline Interferometry and the Gaia space observatory have successfully measured this small effect.

[16] The first VLBI measurement of the apparent motion, over a period of 20 years, of 555 extragalactic objects towards the center of our galaxy at equatorial coordinates of α = 263° and δ = −20° indicated a secular aberration drift 6.4 ±1.5 μas/yr.

[11]: 7 Optical observations using only 33 months of Gaia satellite data of 1.6 million extragalactic sources indicated an acceleration of the solar system of 2.32 ± 0.16 × 10−10 m/s2 and a corresponding secular aberration drift of 5.05 ± 0.35 μas/yr in the direction of α = 269.1° ± 5.4°, δ = −31.6° ± 4.1°.

The Copernican heliocentric theory of the Solar System had received confirmation by the observations of Galileo and Tycho Brahe and the mathematical investigations of Kepler and Newton.

[19] As early as 1573, Thomas Digges had suggested that parallactic shifting of the stars should occur according to the heliocentric model, and consequently if stellar parallax could be observed it would help confirm this theory.

However, in 1680 Jean Picard, in his Voyage d'Uranibourg, stated, as a result of ten years' observations, that Polaris, the Pole Star, exhibited variations in its position amounting to 40″ annually.

John Flamsteed, from measurements made in 1689 and succeeding years with his mural quadrant, similarly concluded that the declination of Polaris was 40″ less in July than in September.

Since the apparent motion was evidently caused neither by parallax nor observational errors, Bradley first hypothesized that it could be due to oscillations in the orientation of the Earth's axis relative to the celestial sphere – a phenomenon known as nutation.

[22] He also investigated the possibility that the motion was due to an irregular distribution of the Earth's atmosphere, thus involving abnormal variations in the refractive index, but again obtained negative results.

This instrument had the advantage of a larger field of view and he was able to obtain precise positions of a large number of stars over the course of about twenty years.

During his first two years at Wanstead, he established the existence of the phenomenon of aberration beyond all doubt, and this also enabled him to formulate a set of rules that would allow the calculation of the effect on any given star at a specified date.

Bradley eventually developed his explanation of aberration in about September 1728 and this theory was presented to the Royal Society in mid January the following year.

The following table shows the magnitude of deviation from true declination for γ Draconis and the direction, on the planes of the solstitial colure and ecliptic prime meridian, of the tangent of the velocity of the Earth in its orbit for each of the four months where the extremes are found, as well as expected deviation from true ecliptic longitude if Bradley had measured its deviation from right ascension: Bradley proposed that the aberration of light not only affected declination, but right ascension as well, so that a star in the pole of the ecliptic would describe a little ellipse with a diameter of about 40", but for simplicity, he assumed it to be a circle.

In the prior century, René Descartes argued that if light were not instantaneous, then shadows of moving objects would lag; and if propagation times over terrestrial distances were appreciable, then during a lunar eclipse the Sun, Earth, and Moon would be out of alignment by hours' motion, contrary to observation.

Huygens commented that, on Rømer's lightspeed data (yielding an earth-moon round-trip time of only seconds), the lag angle would be imperceptible.

What they both overlooked[25] is that aberration (as understood only later) would exactly counteract the lag even if large, leaving this eclipse method completely insensitive to light speed.

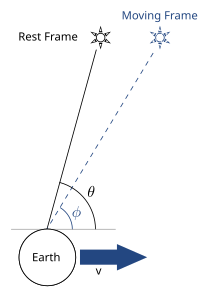

The first classical explanation was provided in 1729, by James Bradley as described above, who attributed it to the finite speed of light and the motion of Earth in its orbit around the Sun.

[3][4] However, this explanation proved inaccurate once the wave nature of light was better understood, and correcting it became a major goal of the 19th century theories of luminiferous aether.

George Stokes proposed a similar theory, explaining that aberration occurs due to the flow of aether induced by the motion of the Earth.

While this is different from the more accurate relativistic result described above, in the limit of small angle and low velocity they are approximately the same, within the error of the measurements of Bradley's day.

In 1810 François Arago performed a similar experiment and found that the aberration was unaffected by the medium in the telescope, providing solid evidence against Young's theory.

[a] With this modification Fresnel obtained Bradley's vacuum result even for non-vacuum telescopes, and was also able to predict many other phenomena related to the propagation of light in moving bodies.

However, the question of aberration was put aside during much of the second half of the 19th century as focus of inquiry turned to the electromagnetic properties of aether.

After working on this problem for a decade, the issues with Stokes' theory caused him to abandon it and to follow Fresnel's suggestion of a (mostly) stationary aether (1892, 1895).

[27][29] Lorentz' theory matched experiment well, but it was complicated and made many unsubstantiated physical assumptions about the microscopic nature of electromagnetic media.

I learned of it through Lorentz' path breaking investigation on the electrodynamics of moving bodies (1895), of which I knew before the establishment of the special theory of relativity.