Ansel Adams

His mother's family came from Baltimore, where his maternal grandfather had a successful freight-hauling business but lost his wealth investing in failed mining and real estate ventures in Nevada.

Then four years old, Adams was uninjured in the initial shaking but was tossed face-first into a garden wall during an aftershock three hours later, breaking and scarring his nose.

He had little patience for games or sports; but he enjoyed the beauty of nature from an early age, collecting bugs and exploring Lobos Creek all the way to Baker Beach and the sea cliffs leading to Lands End,[7][8] "San Francisco's wildest and rockiest coast, a place strewn with shipwrecks and rife with landslides.

Some of the loss was due to his uncle Ansel Easton and Cedric Wright's father George secretly having sold their shares of the company, "knowingly providing the controlling interest" to the Hawaiian Sugar Trust for a large amount of money.

[15] His father raised him to follow the ideas of Ralph Waldo Emerson: to live a modest, moral life guided by a social responsibility to man and nature.

[42] By 1925 he had rejected pictorialism altogether for a more realistic approach that relied on sharp focus, heightened contrast, precise exposure, and darkroom craftsmanship.

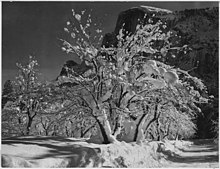

Bender helped Adams produce his first portfolio in his new style, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, which included his famous image Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, which was taken with his Korona view camera, using glass plates and a dark red filter (to heighten the tonal contrasts).

Adams was impressed by the simplicity and detail of Strand's negatives, which showed a style that ran counter to the soft-focus, impressionistic pictorialism still popular at the time.

He decided to broaden his subject matter to include still life and close-up photos and to achieve higher quality by "visualizing" each image before taking it.

He emphasized the use of small apertures and long exposures in natural light, which created sharp details with a wide range of distances in focus, as demonstrated in Rose and Driftwood (1933),[59] one of his finest still-life photographs.

He was inspired partly by the increasing incursion into Yosemite Valley of commercial development, including a pool hall, bowling alley, golf course, shops, and automobile traffic.

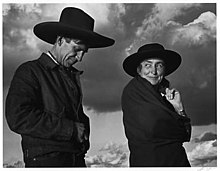

[69][70][note 1] In 1937, Adams, O'Keeffe, and friends organized a month-long camping trip in Arizona, with Orville Cox, the head wrangler at Ghost Ranch, as their guide.

[81] While in New Mexico for the project, Adams photographed a scene of the Moon rising above a modest village with snow-covered mountains in the background, under a dominating black sky.

Although they were legally the property of the U.S. Government, he knew that the National Archives did not take proper care of photographic material, and used various subterfuges to evade queries.

But the position of the Moon allowed the image to be eventually dated from astronomical calculations, and in 1991 Dennis di Cicco of Sky & Telescope determined that Moonrise was made on November 1, 1941.

[103] In 1943, Adams had a camera platform mounted on his station wagon, to afford him a better vantage point over the immediate foreground and a better angle for expansive backgrounds.

Adams invited Dorothea Lange, Imogen Cunningham, and Edward Weston to be guest lecturers, and Minor White to be the principal instructor.

[109] He continued with commercial assignments for another twenty years, and became a consultant, with a monthly retainer, for Polaroid Corporation, which was founded by good friend Edwin Land.

[112] Adams published his fourth portfolio, What Majestic Word, in 1963, and dedicated it to the memory of his Sierra Club friend Russell Varian,[113] who was a co-inventor of the klystron and who had died in 1959.

[132] Romantic landscape artists Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran portrayed the Grand Canyon and Yosemite during the 19th century, followed by photographers Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and George Fiske.

[18] In 1955, Edward Steichen selected Adams's Mount Williamson for the world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition The Family of Man,[136] which was seen by nine million visitors.

At 10 by 12 feet (3.0 by 3.7 m), his was the largest print in the exhibition, presented floor-to-ceiling in a prominent position as the backdrop to the section "Relationships",[137] as a reminder of the essential reliance of humanity on the soil.

[138] In 1932, Adams helped form the anti-pictorialist Group f/64, a loose and relatively short-lived association of like-minded "straight" or "pure" photographers on the West Coast whose members included Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham.

The modernist group favored sharp focus—f/64 being a very small aperture setting that gives great depth of field on large-format view cameras—contact printing, precisely exposed images of natural forms and found objects, and the use of the entire tonal range of a photograph.

The photographer can take light readings of key elements in a scene and use the Zone System to determine how the film must be exposed, developed, and printed to achieve the desired brightness or darkness in the final image.

[149] In 1940, with trustee David H. McAlpin and curator Beaumont Newhall, Adams helped establish the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

[155] The exhibition took aesthetic quality as a guiding principle,[153] a philosophy that ran counter to that of many writers and critics, who argued that the medium's more vernacular use as a means of communication should be more fully represented.

[156] Photographer Ralph Steiner, writing for PM, remarked "on the whole it [MoMA] seems to regard photography as soft music at high tea rather than as a jazz at a beefsteak supper.

[65] In 1980, President Jimmy Carter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, for "his efforts to preserve this country's wild and scenic areas, both on film and on earth.

[173] However, he preferred black-and-white photography, which he believed could be manipulated to produce a wide range of bold, expressive tones, and he felt constricted by the rigidity of the color process.