Antenna (zoology)

Functions may variously include sensing touch, air motion, heat, vibration (sound), and especially smell or taste.

The subdivisions of crustacean antennae have many names, including flagellomeres (a shared term with insects), annuli, articles, and segments.

[2] The second antennae in the burrowing Hippoidea and Corystidae have setae that interlock to form a tube or "snorkel" which funnels filtered water over the gills.

Antennae are the primary olfactory sensors of insects[7] and are accordingly well-equipped with a wide variety of sensilla (singular: sensillum).

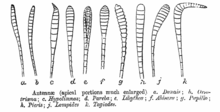

[citation needed] The three basic segments of the typical insect antenna are the scape or scapus (base), the pedicel or pedicellus (stem), and finally the flagellum, which often comprises many units known as flagellomeres.

[11] The scape is mounted in a socket in a more or less ring-shaped sclerotised region called the torulus, often a raised portion of the insect's head capsule.

In many true insects, especially the more primitive groups such as Thysanura and Blattodea, the flagellum partly or entirely consists of a flexibly connected string of small ring-shaped annuli.

For example, the Scarabaeidae have lamellate antennae that can be folded tightly for safety or spread openly for detecting odours or pheromones.

The insect manages such actions by changes in blood pressure, by which it exploits elasticity in walls and membranes in the funicles, which are in effect erectile.

[13] Olfactory receptors on the antennae bind to free-floating molecules, such as water vapour, and odours including pheromones.

The neurons that possess these receptors signal this binding by sending action potentials down their axons to the antennal lobe in the brain.

Antennal clocks exist in monarchs, and they are likely to provide the primary timing mechanism for sun compass orientation.

[17] Giant swallowtail butterflies also rely on antenna sensitivity to volatile compounds to identify host plants.

Similar to halteres in Dipteran insects, the antennae transmit coriolis forces through the Johnston's organ that can then be used for corrective behavior.

[19] To determine whether there may be other antennal sensory inputs, a second group of moths had their antennae amputated and then re-attached, before being tested in the same stability study.

Re-amputation of the antennae caused a drastic decrease in flight stability to match that of the first amputated group.