Coriolis force

The centrifugal force acts outwards in the radial direction and is proportional to the distance of the body from the axis of the rotating frame.

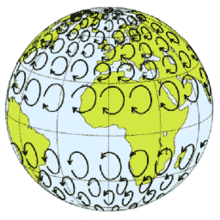

In popular (non-technical) usage of the term "Coriolis effect", the rotating reference frame implied is almost always the Earth.

Because the Earth spins, Earth-bound observers need to account for the Coriolis force to correctly analyze the motion of objects.

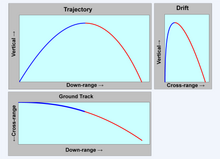

The Earth completes one rotation for each sidereal day, so for motions of everyday objects the Coriolis force is imperceptible; its effects become noticeable only for motions occurring over large distances and long periods of time, such as large-scale movement of air in the atmosphere or water in the ocean, or where high precision is important, such as artillery or missile trajectories.

Italian scientist Giovanni Battista Riccioli and his assistant Francesco Maria Grimaldi described the effect in connection with artillery in the 1651 Almagestum Novum, writing that rotation of the Earth should cause a cannonball fired to the north to deflect to the east.

[2] In 1674, Claude François Milliet Dechales described in his Cursus seu Mundus Mathematicus how the rotation of the Earth should cause a deflection in the trajectories of both falling bodies and projectiles aimed toward one of the planet's poles.

[6] Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis published a paper in 1835 on the energy yield of machines with rotating parts, such as waterwheels.

[12] In 1856, William Ferrel proposed the existence of a circulation cell in the mid-latitudes with air being deflected by the Coriolis force to create the prevailing westerly winds.

Viewed from outer space, the object does not appear to go due north, but has an eastward motion (it rotates around toward the right along with the surface of the Earth).

[23][24] Though not obvious from this example, which considers northward motion, the horizontal deflection occurs equally for objects moving eastward or westward (or in any other direction).

[29] An atmospheric system moving at U = 10 m/s (22 mph) occupying a spatial distance of L = 1,000 km (621 mi), has a Rossby number of approximately 0.1.

However, an unguided missile obeys exactly the same physics as a baseball, but can travel far enough and be in the air long enough to experience the effect of Coriolis force.

Straight-line paths are followed because the ball is in free flight, so this observer requires that no net force is applied.

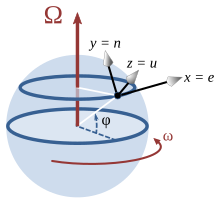

The rotation vector, velocity of movement and Coriolis acceleration expressed in this local coordinate system [listing components in the order east (e), north (n) and upward (u)] are:[34] When considering atmospheric or oceanic dynamics, the vertical velocity is small, and the vertical component of the Coriolis acceleration (

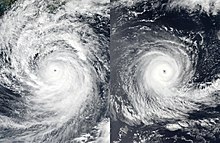

Though the circulation is not as significant as that in the air, the deflection caused by the Coriolis effect is what creates the spiralling pattern in these gyres.

The stronger the force from the Coriolis effect, the faster the wind spins and picks up additional energy, increasing the strength of the hurricane.

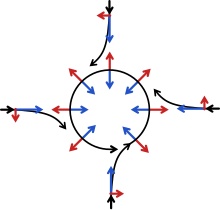

[38][better source needed] If a low-pressure area forms in the atmosphere, air tends to flow in towards it, but is deflected perpendicular to its velocity by the Coriolis force.

[43] The Coriolis effect strongly affects the large-scale oceanic and atmospheric circulation, leading to the formation of robust features like jet streams and western boundary currents.

Since vertical movement is usually of limited extent and duration, the size of the effect is smaller and requires precise instruments to detect.

For example, idealized numerical modeling studies suggest that this effect can directly affect tropical large-scale wind field by roughly 10% given long-duration (2 weeks or more) heating or cooling in the atmosphere.

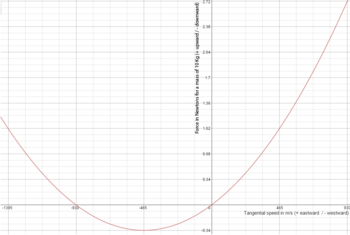

[49] The above example can be used to explain why the Eötvös effect starts diminishing when an object is traveling westward as its tangential speed increases above Earth's rotation (465 m/s).

Contrary to popular misconception, bathtubs, toilets, and other water receptacles do not drain in opposite directions in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Without such careful preparation, the Coriolis effect will be much smaller than various other influences on drain direction[53] such as any residual rotation of the water[54] and the geometry of the container.

For the everyday observations of the kitchen sink and bath-tub variety, the direction of the vortex seems to vary in an unpredictable manner with the date, the time of day, and the particular household of the experimenter.

In a properly designed experiment, the vortex is produced by Coriolis forces, which are counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere.Lloyd Trefethen reported clockwise rotation in the Southern Hemisphere at the University of Sydney in five tests with settling times of 18 h or more.

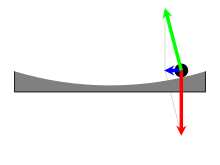

However, if the turntable surface has the correct paraboloid (parabolic bowl) shape (see the figure) and rotates at the corresponding rate, the force components shown in the figure make the component of gravity tangential to the bowl surface exactly equal to the centripetal force necessary to keep the object rotating at its velocity and radius of curvature (assuming no friction).

[62][63] Discs cut from cylinders of dry ice can be used as pucks, moving around almost frictionlessly over the surface of the parabolic turntable, allowing effects of Coriolis on dynamic phenomena to show themselves.

This leads to a mixing in molecular spectra between the rotational and vibrational levels, from which Coriolis coupling constants can be determined.

Flies (Diptera) and some moths (Lepidoptera) exploit the Coriolis effect in flight with specialized appendages and organs that relay information about the angular velocity of their bodies.

Coriolis forces resulting from linear motion of these appendages are detected within the rotating frame of reference of the insects' bodies.

Left : The inertial point of view.

Right : The co-rotating point of view.

Red : gravity

Green : the normal force

Blue : the net resultant centripetal force .