Battle of Antietam

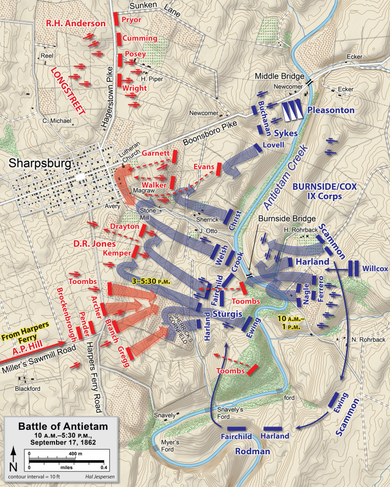

In the afternoon, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right.

At a crucial moment, Confederate Major General A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle.

Barton W. Mitchell and First Sergeant John M. Bloss[16][17] of the 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry) discovered a mislaid copy of Lee's detailed battle plans—Special Order 191—wrapped around three cigars.

The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically (to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland), thus making each subject to isolation and defeat if McClellan could move quickly enough.

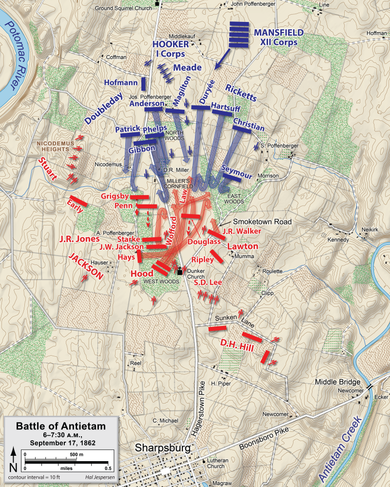

[71] "... every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the [Confederates] slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before."

[74] In an effort to turn the Confederate left flank and relieve the pressure on Mansfield's men, Sumner's II Corps was ordered at 7:20 a.m. to send two divisions into battle.

Sedgwick's division of 5,400 men was the first to ford the Antietam, and they entered the East Woods with the intention of turning left and forcing the Confederates south into the assault of Ambrose Burnside's IX Corps.

By this time, Sumner's aide (and son) located French, described the terrible fighting in the West Woods and relayed an order for him to divert Confederate attention by attacking their center.

But Hill's men were in a strong defensive position, atop a gradual ridge, in a sunken road worn down by years of wagon traffic, which formed a natural trench.

The first brigade to attack, mostly inexperienced troops commanded by Brigadier General Max Weber, was quickly cut down by heavy rifle fire; neither side deployed artillery at this point.

The second attack, more raw recruits under Colonel Dwight Morris, was also subjected to heavy fire but managed to beat back a counterattack by the Alabama Brigade of Robert Rodes.

[85] Reinforcements were arriving on both sides, and by 10:30 a.m. Robert E. Lee sent his final reserve division—some 3,400 men under Major General Richard H. Anderson—to bolster Hill's line and extend it to the right, preparing an attack that would envelop French's left flank.

As they advanced with emerald green flags snapping in the breeze, a regimental chaplain, Father William Corby, rode back and forth across the front of the formation shouting words of conditional absolution prescribed by the Roman Catholic Church for those who were about to die.

A counterattack with 200 men led by D.H. Hill got around the Federal left flank near the sunken road, and although they were driven back by a fierce charge of the 5th New Hampshire, this stemmed the collapse of the center.

The Rebels, under Manning, had made a second assault on the high ground to the left (held by Greene) overlooking the road that temporarily around noon,[96] but Smith's Division of VI Corps recaptured it.

The remaining 400 men—the 2nd and 20th Georgia regiments, under the command of Brigadier General Robert Toombs, with two artillery batteries—defended Rohrbach's Bridge, a three-span, 125-foot (38 m) stone structure that was the southernmost crossing of the Antietam.

After receiving punishing fire for 15 minutes, the Connecticut men withdrew with 139 casualties, one-third of their strength, including their commander, Colonel Henry W. Kingsbury, who was fatally wounded.

[109] Crook's main assault went awry when his unfamiliarity with the terrain caused his men to reach the creek a quarter mile (400 m) upstream from the bridge, where they exchanged volleys with Confederate skirmishers for the next few hours.

He increased the pressure by sending his inspector general, Colonel Delos B. Sackett, to confront Burnside, who reacted indignantly: "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders.

It was led by the 51st New York and the 51st Pennsylvania, who, with adequate artillery support and a promise that a recently canceled whiskey ration would be restored if they were successful, charged downhill and took up positions on the east bank.

Burnside's plan was to move around the weakened Confederate right flank, converge on Sharpsburg, and cut Lee's army off from Boteler's Ford, their only escape route across the Potomac.

[116] An initial assault led by the 79th New York "Cameron Highlanders" succeeded against Jones's outnumbered division, which was pushed back past Cemetery Hill and to within 200 yards (200 m) of Sharpsburg.

At 3:40 p.m., Brigadier General Maxcy Gregg's brigade of South Carolinians attacked the 16th Connecticut on Rodman's left flank in the cornfield of farmer John Otto.

The 4th Rhode Island came up on the right, but they had poor visibility amid the high stalks of corn, and they were disoriented because many of the Confederates were wearing Union uniforms captured at Harpers Ferry.

In fact, however, McClellan had two fresh corps in reserve, Porter's V and Franklin's VI, but he was too cautious, concerned he was greatly outnumbered and that a massive counterstrike by Lee was imminent.

Overall, both sides lost a combined total of 22,727 casualties in a single day, almost the same amount as the number of losses that had shocked the nation at the 2-day Battle of Shiloh five months earlier.

General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck wrote in his official report, "The long inactivity of so large an army in the face of a defeated foe, and during the most favorable season for rapid movements and a vigorous campaign, was a matter of great disappointment and regret.

In July 1863 the dual Union triumphs at Gettysburg and Vicksburg struck another blow that blunted a renewed Confederate offensive in the East and cut off the western third of the Confederacy from the rest.

[135]The results of Antietam also allowed President Lincoln to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, which gave Confederate states until January 1, 1863, to end their rebellion or else lose their slaves.

Although Lincoln had intended to do so earlier, Secretary of State William H. Seward, at a cabinet meeting, advised him to wait until the Union won a significant victory so as to avoid the perception that it was issued out of desperation.

Army of the Potomac (USA)

Army of Northern Virginia (CSA)

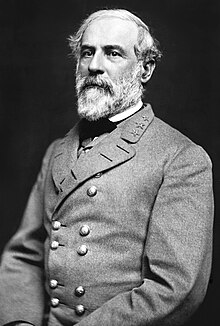

Photograph by Alexander Gardner

9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

by Edwin Forbes