Antisymmetric exchange

Quantitatively, it is a term in the Hamiltonian which can be written as In magnetically ordered systems, it favors a spin canting of otherwise parallel or antiparallel aligned magnetic moments and thus, is a source of weak ferromagnetic behavior in an antiferromagnet.

The interaction is fundamental to the production of magnetic skyrmions and explains the magnetoelectric effects in a class of materials termed multiferroics.

The discovery of antisymmetric exchange originated in the early 20th century from the controversial observation of weak ferromagnetism in typically antiferromagnetic α-Fe2O3 crystals.

[1] In 1958, Igor Dzyaloshinskii provided evidence that the interaction was due to the relativistic spin lattice and magnetic dipole interactions based on Lev Landau's theory of phase transitions of the second kind.

[2] In 1960, Toru Moriya identified the spin-orbit coupling as the microscopic mechanism of the antisymmetric exchange interaction.

[1] Moriya referred to this phenomenon specifically as the "antisymmetric part of the anisotropic superexchange interaction."

The simplified naming of this phenomenon occurred in 1962, when D. Treves and S. Alexander of Bell Telephone Laboratories simply referred to the interaction as antisymmetric exchange.

Because of their seminal contributions to the field, antisymmetric exchange is sometimes referred to as the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction.

[3] The functional form of the DMI can be obtained through a second-order perturbative analysis of the spin-orbit coupling interaction,

out as In an actual crystal, symmetries of neighboring ions dictate the magnitude and direction of the vector

A recent advancement in broadband electron spin resonance coupled with optical detection (OD-ESR) allows for characterization of the DMI vector for rare-earth ion materials with no assumptions and across a large spectrum of magnetic field strength.

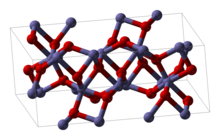

The structure also contains the same unit cell as α-Fe2O3 and α-Cr2O3 which possess D63d space group symmetry.

The upper half unit cell displayed shows four M3+ ions along the space diagonal of the rhombohedron.

In the Fe2O3 structure, the spins of the first and last metal ion are positive while the center two are negative.

In the α-Cr2O3 structure, the spins of the first and third metal ion are positive while the second and fourth are negative.

Both compounds are antiferromagnetic at cold temperatures (<250K), however α-Fe2O3 above this temperature undergoes a structural change where its total spin vector no longer points along the crystal axis but at a slight angle along the basal (111) plane.

It is thus the combination of the distribution of ion spins, the misalignment of the total spin vector, and the resulting antisymmetry of the unit cell that gives rise to the antisymmetric exchange phenomenon seen in these crystal structures.

They exist in spiral or hedgehog configurations that are stabilized by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction.

Skyrmions are topological in nature, making them promising candidates for future spintronic devices.

Antisymmetric exchange is of importance for the understanding of magnetism induced electric polarization in a recently discovered class of multiferroics.

In certain magnetic structures, all ligand ions are shifted into the same direction, leading to a net electric polarization.

Such applications include tunnel magnetoresistance (TMR) sensors, spin valves with electric field tunable functions, high-sensitivity alternating magnetic field sensors, and electrically tunable microwave devices.

[7][8] Most multiferroic materials are transition metal oxides due to the magnetization potential of the 3d electrons.