Ligand

The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's electron pairs, often through Lewis bases.

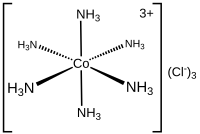

Ligands are classified in many ways, including: charge, size (bulk), the identity of the coordinating atom(s), and the number of electrons donated to the metal (denticity or hapticity).

The first to use the term "ligand" were Alfred Werner and Carl Somiesky, in relation to silicon chemistry.

He resolved the first coordination complex called hexol into optical isomers, overthrowing the theory that chirality was necessarily associated with carbon compounds.

Binding of the metal with the ligands results in a set of molecular orbitals, where the metal can be identified with a new HOMO and LUMO (the orbitals defining the properties and reactivity of the resulting complex) and a certain ordering of the 5 d-orbitals (which may be filled, or partially filled with electrons).

In an octahedral environment, the 5 otherwise degenerate d-orbitals split in sets of 3 and 2 orbitals (for a more in-depth explanation, see crystal field theory): The energy difference between these 2 sets of d-orbitals is called the splitting parameter, Δo.

For the purposes of ranking ligands, however, the properties of the octahedral complexes and the resulting Δo has been of primary interest.

The arrangement of the d-orbitals on the central atom (as determined by the 'strength' of the ligand), has a strong effect on virtually all the properties of the resulting complexes.

E.g., the energy differences in the d-orbitals has a strong effect in the optical absorption spectra of metal complexes.

It turns out that valence electrons occupying orbitals with significant 3 d-orbital character absorb in the 400–800 nm region of the spectrum (UV–visible range).

The absorption of light (what we perceive as the color) by these electrons (that is, excitation of electrons from one orbital to another orbital under influence of light) can be correlated to the ground state of the metal complex, which reflects the bonding properties of the ligands.

The metal–ligand bond can be further stabilised by a formal donation of electron density back to the ligand in a process known as back-bonding.

In this case a filled, central-atom-based orbital donates density into the LUMO of the (coordinated) ligand.

Chelating ligands are commonly formed by linking donor groups via organic linkers.

A classic bidentate ligand is ethylenediamine, which is derived by the linking of two ammonia groups with an ethylene (−CH2CH2−) linker.

A classic example of a polydentate ligand is the hexadentate chelating agent EDTA, which is able to bond through six sites, completely surrounding some metals.

Denticity (represented by κ) is nomenclature that described to the number of noncontiguous atoms of a ligand bonded to a metal.

Hapticity (represented by Greek letter η) refers to the number of contiguous atoms that comprise a donor site and attach to a metal center.

Butadiene forms both η2 and η4 complexes depending on the number of carbon atoms that are bonded to the metal.

Virtually all inorganic solids with simple formulas are coordination polymers, consisting of metal ion centres linked by bridging ligands.

This group of materials includes all anhydrous binary metal ion halides and pseudohalides.

Bridging ligands, capable of coordinating multiple metal ions, have been attracting considerable interest because of their potential use as building blocks for the fabrication of functional multimetallic assemblies.

Some ligands can bond to a metal center through the same atom but with a different number of lone pairs.

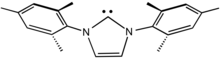

Often bulky ligands are employed to simulate the steric protection afforded by proteins to metal-containing active sites.

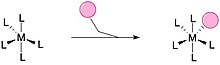

Hemilabile ligands contain at least two electronically different coordinating groups and form complexes where one of these is easily displaced from the metal center while the other remains firmly bound, a behaviour which has been found to increase the reactivity of catalysts when compared to the use of more traditional ligands.

Describing the bonding of non-innocent ligands often involves writing multiple resonance forms that have partial contributions to the overall state.

Beyond the classical Lewis bases and anions, all unsaturated molecules are also ligands, utilizing their pi electrons in forming the coordinate bond.

Also, metals can bind to the σ bonds in for example silanes, hydrocarbons, and dihydrogen (see also: Agostic interaction).