Electron paramagnetic resonance

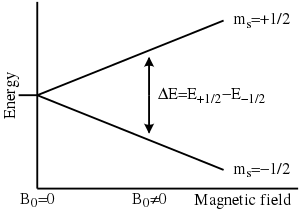

The basic concepts of EPR are analogous to those of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), but the spins excited are those of the electrons instead of the atomic nuclei.

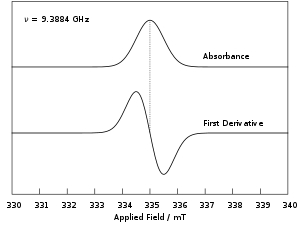

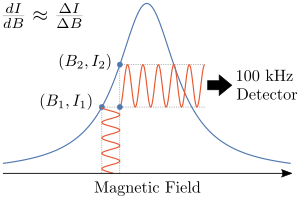

Furthermore, EPR spectra can be generated by either varying the photon frequency incident on a sample while holding the magnetic field constant or doing the reverse.

Note field modulation is unique to continuous wave EPR measurements and spectra resulting from pulsed experiments are presented as absorption profiles.

There are several important consequences of this: Knowledge of the g-factor can give information about a paramagnetic center's electronic structure.

, the implication is that the ratio of the unpaired electron's spin magnetic moment to its angular momentum differs from the free-electron value.

Because the mechanisms of spin–orbit coupling are well understood, the magnitude of the change gives information about the nature of the atomic or molecular orbital containing the unpaired electron.

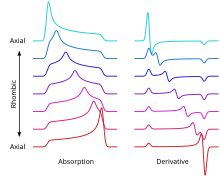

Choosing an appropriate coordinate system (say, x,y,z) allows one to "diagonalize" this tensor, thereby reducing the maximal number of its components from 9 to 3: gxx, gyy and gzz.

For a single spin experiencing only Zeeman interaction with an external magnetic field, the position of the EPR resonance is given by the expression gxxBx + gyyBy + gzzBz.

For a large ensemble of randomly oriented spins (as in a fluid solution), the EPR spectrum consists of three peaks of characteristic shape at frequencies gxxB0, gyyB0 and gzzB0.

The determination of the absolute value of the g factor is challenging due to the lack of a precise estimate of the local magnetic field at the sample location.

For the initial calibration of g factor standards, Herb et al. introduced a precise procedure by using double resonance techniques based on the Overhauser shift.

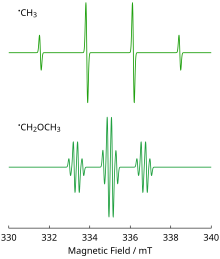

While it is easy to predict the number of lines, the reverse problem, unraveling a complex multi-line EPR spectrum and assigning the various spacings to specific nuclei, is more difficult.

EPR/ESR spectroscopy is used in various branches of science, such as biology, chemistry and physics, for the detection and identification of free radicals in the solid, liquid, or gaseous state,[9] and in paramagnetic centers such as F-centers.

Specially-designed nonreactive radical molecules can attach to specific sites in a biological cell, and EPR spectra then give information on the environment of the spin labels.

Spin-labeled fatty acids have been extensively used to study dynamic organisation of lipids in biological membranes,[11] lipid-protein interactions[12] and temperature of transition of gel to liquid crystalline phases.

This method is suitable for measuring gamma and X-rays, electrons, protons, and high-linear energy transfer (LET) radiation of doses in the 1 Gy to 100 kGy range.

Radiation damage over long periods of time creates free radicals in tooth enamel, which can then be examined by EPR and, after proper calibration, dated.

Similarly, material extracted from the teeth of people during dental procedures can be used to quantify their cumulative exposure to ionizing radiation.

People (and other mammals[21]) exposed to radiation from the atomic bombs,[22] from the Chernobyl disaster,[23][24] and from the Fukushima accident have been examined by this method.

The technique has a long history of being coupled to the field, starting with a report in 1958 using EPR to detect free radicals generated via electrochemistry.

In an experiment performed by Austen, Given, Ingram, and Peover, solutions of aromatics were electrolyzed and placed into an EPR instrument, resulting in a broad signal response.

[27] While this result could not be used for any specific identification, the presence of an EPR signal validated the theory that free radical species were involved in electron transfer reactions as an intermediate state.

Soon after, other groups discovered the possibility of coupling in situ electrolysis with EPR, producing the first resolved spectra of the nitrobenzene anion radical from a mercury electrode sealed within the instrument cavity.

[28] Since then, the impact of EPR on the field of electrochemistry has only expanded, serving as a way to monitor free radicals produced by other electrolysis reactions.

[31] In the field of quantum computing, pulsed EPR is used to control the state of electron spin qubits in materials such as diamond, silicon and gallium arsenide.

However, for many years the use of electromagnets to produce the needed fields above 1.5 T was impossible, due principally to limitations of traditional magnet materials.

EPR experiments often are conducted at X and, less commonly, Q bands, mainly due to the ready availability of the necessary microwave components (which originally were developed for radar applications).

> 40 GHz, in the millimeter wavelength region, offer the following advantages: This was demonstrated experimentally in the study of various biological, polymeric and model systems at D-band EPR.

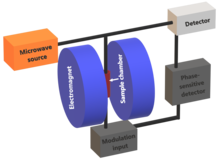

Resonance means the cavity stores microwave energy and its ability to do this is given by the quality factor Q, defined by the following equation:

When the magnetic field strength is such that an absorption event occurs, the value of Q will be reduced due to the extra energy loss.