Antisymmetry

Building upon X-bar theory, it proposes a universal, fundamental word order for phrases (branching) across languages: specifier-head-complement.

This means a phrase typically starts with an introductory element (specifier), followed by the core (head, often a verb or noun), and then additional information (complement).

[citation needed] This framework is important for syntacticians as it offers a restrictive theory of possible sentence structures, potentially explaining cross-linguistic variations in word order and constraining the range of grammatical analyses.

Informally, Kayne's theory states that if a nonterminal category A asymmetrically c-commands another nonterminal category B, all the terminal nodes dominated by A must precede all of the terminal nodes dominated by B (this statement is commonly referred to as the "Linear Correspondence Axiom" or LCA).

Perhaps the biggest challenge for antisymmetry is to explain the wide variety of different surface orders across languages.

From the mid-1980s onwards, the standard analysis of wh-movement involved the wh-phrase moving leftward to a position on the left edge of the clause called [Spec,CP].

would proceed roughly as follows: The Japanese equivalent of this sentence is as follows[6] (note the lack of wh-movement): John-waJohn-TOPnani-owhat-ACCkaimashitaboughtkaQJohn-wa nani-o kaimashita kaJohn-TOP what-ACC bought Q'What did John buy'Japanese has an overt "question particle" (ka), which appears at the end of the sentence in questions.

Kayne suggests that in Japanese, the whole of the clause (apart from the question particle in C) has moved to the [Spec,CP] position.

A possible alternative to the antisymmetric explanation could be based on the difficulty of parsing languages with rightward movement.

The unwanted structures are then rescued by movement: deleting the phonetic content of the moved element neutralizes the linearization problem.

[8] Dynamic Antisymmetry aims at unifying a movement and phrase structure, which otherwise are independent properties.

Kayne proposed recasting the antisymmetry of natural language as a condition of "Merge", the operation which combines two elements into one.

[9] Antisymmetry theory rejects the head-directionality parameter as such: it claims that at an underlying level, all languages are head-initial.

Examples of linguistic asymmetries which may be cited in support of the theory (although they do not concern head direction) are: In arguing for a universal underlying Head-Complement order, Kayne uses the concept of a probe-goal search (based on the Minimalist program).

This implies (according to the theory) an ordering whereby probe comes before the goal, i.e. head precedes complement.

He represents the relevant scheme as follows:[16] The specifier, at first internal to the complement, is moved to the unoccupied position to the left of the head.

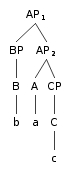

In terms of merged pairs, this structure can also be represented as: This process can be mapped onto X-bar syntactic trees as shown in the adjacent diagram.

It has been pointed out, though, that in predominantly head-final languages such as Japanese and Basque, this would involve complex and massive leftward movement, which violates the ideal of grammatical simplicity.

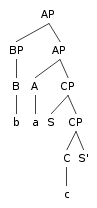

[17] An example of the type of movement scheme that would need to be envisaged is provided by Tokizaki:[18] Here, at each phrasal level in turn, the head of the phrase moves from left to right position relative to its complement.

The eventual result reflects the ordering of complex nested phrases found in languages such as Japanese.

An attempt to provide evidence for Kayne's scheme is made by Lin,[19] who considered Standard Chinese sentences with the sentence-final particle le.

Based on prior work by James Huang,[20] it is postulated that (a) adverbials of this type are subject to movement at logical form (LF) level (even though, in Chinese, they do not display wh-movement at surface level); and (b) movement is not possible from within a non-complement (Huang's Condition on Extraction Domain or CED[clarification needed]).

This would imply that zenmeyang could not appear in a verb phrase with sentence-final le, assuming the above analysis, since that verb phrase has moved into a non-complement (specifier) position, and thus further movement (such as that which zenmeyang is required to undergo at LF level) is not possible.

Lin cites this and other related findings as evidence that the above analysis is correct, supporting the view that Chinese aspect phrases are deeply head-initial.

[22] In this approach the relative positions of head and complement that are found at this surface level, which show variation both between and within languages (see above), must be treated as the "true" orderings.

Takita argues against the conclusion of Kayne's Antisymmetry Theory, which states that all languages are head-initial at an underlying level.

[23] [CP1 Taro-gaTaro-NOM[CP2[IP2 Hanako-gaHanako-NOM[VP2 hon-obook-ACCsute]-saediscard-evenshitadidto]Comotteiru]think[CP1 Taro-ga [CP2[IP2 Hanako-ga [VP2 hon-o sute]-sae shita to] omotteiru]{} Taro-NOM {} Hanako-NOM {} book-ACC discard-even did C think'Taro thinks [that Hanako [even discarded his books]]'(Takita 2009 57: (33a)[CP1[VP2 Hon-obook-ACCsute]-saeidiscard-evenTaro-gaTaro-NOM[CP2[IP2 Hanako-gaHanako-NOMshita]didto]Comotteiruthink[CP1[VP2 Hon-o sute]-saei Taro-ga [CP2[IP2 Hanako-ga shita] to] omotteiru{} book-ACC discard-even Taro-NOM {} Hanako-NOM did C think'[Even discarded his books], Taro thinks [that Hanako did ti]'(Takita 2009 57: (33b)In (b), the fronted VP precedes the matrix subject, confirming that the VP is located in the matrix clause.

[23] Thus Takita shows that surface head-final structures in Japanese do not block movement, as they do in Chinese.

He concludes that, because it does not block movement as shown in previous sections, Japanese is a genuinely head-final language, and not derived from an underlying, head-initial structure.

Takita briefly applies the same tests to Turkish, another seemingly head-final language, and reports similar results.