Chinese grammar

[1] Additionally, the present progressive aspect marker zhe (着) can be inserted between these two parts to form tiàozhewǔ (跳着舞; 'to be dancing').

[citation needed] Many monosyllabic words have alternative disyllabic forms with virtually the same meaning, such as dàsuàn (大蒜; 'big-garlic') for suàn (蒜; 'garlic').

今天jīntiānToday爬páclimb山shānmountain,明天míngtiāntomorrow露lùoutdoors营。yíngcamp[今天爬山,明天露營。] 今天 爬 山 明天 露 营。jīntiān pá shān míngtiān lù yíngToday climb mountain, tomorrow outdoors campToday hike up mountains, tomorrow camp outdoors.In the next example the subject is omitted and the object is topicalized by being moved into subject position, to form a passive-type sentence.

For example: 我wǒI打dǎhit破pòbroken了lePFV盘子。pánziplate[我打破了盤子。] 我 打 破 了 盘子。wǒ dǎ pò le pánziI hit broken PFV plateI broke a plate.我wǒI把bǎba盘子pánziplate打dǎhit破pòbroken了。lePFV[我把盤子打破了。] 我 把 盘子 打 破 了。wǒ bǎ pánzi dǎ pò leI ba plate hit broken PFVI make the plate brokenOther markers can be used in a similar way as bǎ, such as the formal jiāng (将; 將, literally "lead") : 将JiāngJiāng办理bàn-lǐhandle情形qíng-xíngstatus签qiānsign报bàoreport长官。zhǎng-guānsuperior[將辦理情形簽報長官。] 将 办理 情形 签 报 长官。Jiāng bàn-lǐ qíng-xíng qiān bào zhǎng-guānJiāng handle status sign report superiorSubmit the implementation status report to the superior, and ask for approval.and colloquial ná (拿, literally "get") 他Tāhe能néngcan拿náná我wǒme怎样?zěn-yàngwhat[他能拿我怎樣?]

Most classifiers originated as independent words in Classical Chinese, so they are generally associated with certain groups of nouns with common properties related to their own classical meaning, for example:[15] (Original meaning) (twigs are long and thin) liǎng-tiáo-shé (两条蛇; 兩條蛇, "two snakes") (a handle to hold) liǎng-bǎ-sǎn (两把伞; 兩把傘, "two umbrellas") ("extended" like a bow) liǎng zhāng máo-pí (两张毛皮; 兩張毛皮, "two furs") Therefore, collocation of classifiers and noun sometimes depends on how native speakers realize them.

For example, the noun zhuōzi (桌子, "table") is associated with the classifier zhāng (张; 張), due to the sheet-like table-top.

Plurals are formed by adding men (们; 們): wǒmen (我们; 我們, "we, us"), nǐmen (你们; 你們, "you"), tāmen (他们/她们/它们/它们; 他們/她們/牠們/它們, "they/them").

[16] The alternative "inclusive" word for "we/us"—zán (咱) or zá[n]men (咱们; 咱們), specifically including the listener[17] (like the difference between English let us and let's)—is used colloquially.

These include three words for "often", cháng (常), chángcháng (常常) and jīngcháng (经常; 經常); dōu (都, "all"); jiù (就, "then"); and yòu (又, "again").

The postpositions—which include shàng (上, "up, on"), xià (下, "down, under"), lǐ (里; 裡, "in, within"), nèi (内, "inside") and wài (外, "outside")—may also be called locative particles.

Some nouns which can be understood to refer to a specific place, like jiā (家, home) and xuéxiào (学校; 學校, "school"), may optionally omit the locative particle.

If there is no standard of comparison—i.e., a than phrase—then the adjective can be marked as comparative by a preceding adverb bǐjiào (比较; 比較), jiào (较; 較) or gèng (更), all meaning "more".

There are two aspect markers that are especially commonly used with past events: the perfective-aspect le (了) and the experiential guo (过; 過).

Some examples: 我们wǒmenWe被bèiby他tāhim骂màscolded了。lePFV[我們被他罵了。] 我们 被 他 骂 了。wǒmen bèi tā mà leWe by him scolded PFVWe were scolded by him.他tāHe被bèiby我wǒme打dǎbeaten了lePFV一yíone顿。dùnevent-CL[他被我打了一頓。] 他 被 我 打 了 一 顿。tā bèi wǒ dǎ le yí dùnHe by me beaten PFV one event-CLHe was beaten up by me once.The most commonly used negating element is bù (不), pronounced with second tone when followed by a fourth tone.

However, the verb yǒu (有)—which can mean either possession, or "there is/are" in existential clauses—is negated using méi (没; 沒) to produce méiyǒu (没有; 沒有; 'not have').

For negation of a verb intended to denote a completed event, méi or méiyǒu is used instead of bù (不), and the aspect marker le (了) is then omitted.

Other items used as negating elements in certain compound words include wú (无; 無),wù (勿), miǎn (免) and fēi (非).

A double negative makes a positive, as in sentences like wǒ bú shì bù xǐhuān tā (我不是不喜欢她; 我不是不喜歡她, "It's not that I don't like her" ).

Chinese auxiliaries include néng and nénggòu (能 and 能够; 能夠, "can"); huì (会; 會, "know how to"); kéyǐ (可以, "may"); gǎn (敢, "dare"); kěn (肯, "be willing to"); yīnggāi (应该; 應該, "should"); bìxū (必须; 必須, "must"); etc.

听tīnghear懂dǒngunderstand[聽懂] 听 懂tīng dǒnghear understandto understand something you hearSince they indicate an absolute result, such double verbs necessarily represent a completed action, and are thus negated using méi (没; 沒): 没méinot听tīnghear懂dǒngunderstand[沒聽懂] 没 听 懂méi tīng dǒngnot hear understandto have not understood something you hearThe morpheme de (得) is placed between the double verbs to indicate possibility or ability.

Some more examples of resultative complements, used in complete sentences: 他tāhe把bǎobject-CL盘子pánziplate打dǎhit破pòbreak了。lePRF[他把盤子打破了。] 他 把 盘子 打 破 了。tā bǎ pánzi dǎ pò lehe object-CL plate hit break PRFHe hit/dropped the plate, and it broke.Double-verb construction where the second verb, "break", is a suffix to the first, and indicates what happens to the object as a result of the action.

这zhè(i)this部bù 电影diànyǐngmovie我wǒI看kànwatch不bùimpossible/unable懂。dǒngunderstand[這部電影我看不懂。] 这 部 电影 我 看 不 懂。zhè(i) bù diànyǐng wǒ kàn bù dǒngthis {} movie I watch impossible/unable understandI can't understand this movie even though I watched it.Another double-verb where the second verb, "understand", suffixes the first and clarifies the possibility and success of the relevant action.

The simplest directional complements are qù (去, "to go") and lái (来; 來, "to come"), which may be added after a verb to indicate movement away from or towards the speaker, respectively.

我wǒI坐zuòsit飞机fēijīairplane从cóngfrom上海ShànghǎiShanghai到dàoarrive(to)北京BěijīngBeijing去。qù.go[我坐飛機從上海到北京去。] 我 坐 飞机 从 上海 到 北京 去。wǒ zuò fēijī cóng Shànghǎi dào Běijīng qù.I sit airplane from Shanghai arrive(to) Beijing goI'll go from Shanghai to Beijing by plane.Here there are three coverbs: zuò (坐 "by"), cóng (从; 從, "from"), and dào (到, "to").

The first verb may be something like gěi (给, "allow", or "give" in other contexts), ràng (让; 讓, "let"), jiào (叫, "order" or "call") or shǐ (使, "make, compel"), qǐng (请; 請, "invite"), or lìng (令, "command").

In the following example the construction is used twice: 他tāhe要yàowant我wǒme请qǐnginvite他tāhim喝hēdrink啤酒。píjiǔbeer[他要我請他喝啤酒。] 他 要 我 请 他 喝 啤酒。tā yào wǒ qǐng tā hē píjiǔhe want me invite him drink beerHe wants me to treat him [to] beer.Chinese has a number of sentence-final particles – these are weak syllables, spoken with neutral tone, and placed at the end of the sentence to which they refer.

They are often called modal particles or yǔqì zhùcí (语气助词; 語氣助詞), as they serve chiefly to express grammatical mood, or how the sentence relates to reality and/or intent.

[49] The demonstrative pronouns zhè (这; 這, "this"), and nà (那, "that") may be optionally pluralized by the addition of xiē (些,"few"), making zhèxiē (这些; 這些, "these") and nàxiē (那些, "those").

[53] Similarly, words like jìrán (既然, "since/in response to"), rúguǒ (如果) or jiǎrú (假如) "if", zhǐyào (只要 "provided that") correlate with an adverb jiù (就, "then") or yě (也, "also") in the main clause, to form conditional sentences.

There are also similar constructions for conditionals: rúguǒ /jiǎrú/zhǐyào ... dehuà (如果/假如/只要...的话, "if ... then"), where huà (话; 話) literally means "narrative, story".

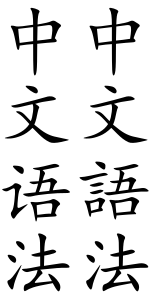

[ 中文 語法 ],

meaning "Chinese grammar", written vertically in simplified (left) and traditional (right) forms