Antithrombin

α-Antithrombin is the dominant form of antithrombin found in blood plasma and has an oligosaccharide occupying each of its four glycosylation sites.

Cow, sheep, rabbit, mouse, and human antithrombins share between 84 and 89% amino acid sequence identity.

For this reason many of the antithrombin structures stored in the protein data bank and presented in this article show variable glycosylation patterns.

[12] The formation of an antithrombin-protease complex involves an interaction between the protease and a specific reactive peptide bond within antithrombin.

[12] It is thought that protease enzymes become trapped in inactive antithrombin-protease complexes as a consequence of their attack on the reactive bond.

Although attacking a similar bond within the normal protease substrate results in rapid proteolytic cleavage of the substrate, initiating an attack on the antithrombin reactive bond causes antithrombin to become activated and trap the enzyme at an intermediate stage of the proteolytic process.

[22] However, bonds P3-P4 and P1'-P2' can be rapidly cleaved by neutrophil elastase and the bacterial enzyme thermolysin, respectively, resulting in inactive antithrombins no longer able to inhibit thrombin activity.

[23] The rate of antithrombin's inhibition of protease activity is greatly enhanced by its additional binding to heparin, as is its inactivation by neutrophil elastase.

[29] In one mechanism heparin stimulation of Factor IXa and Xa inhibition depends on a conformational change within antithrombin involving the reactive site loop and is thus allosteric.

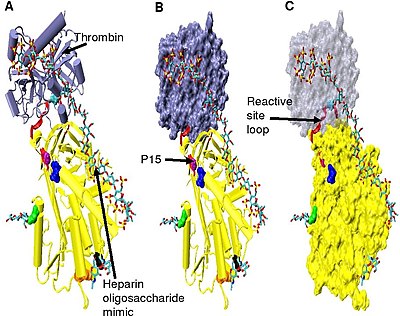

[18][31][32] In the absence of heparin, amino acids P14 and P15 (see Figure 3) from the reactive site loop are embedded within the main body of the protein (specifically the top of beta sheet A).

The conformational change most relevant for Factor IXa and Xa inhibition involves the P14 and P15 amino acids within the N-terminal region of the reactive site loop (circled in Figure 4 model B).

[30] Increased thrombin inhibition requires the minimal heparin pentasaccharide plus at least an additional 13 monomeric units.

[34] The hinge region of antithrombin in the Figure 5 complex could not be modelled due to its conformational flexibility, and amino acids P9-P14 are not seen in this structure.

[35] The difference in dissociation constant between the two is threefold for the pentasaccharide shown in Figure 3 and greater than tenfold for full length heparin, with β-antithrombin having a higher affinity.

[36] The higher affinity of β-antithrombin is thought to be due to the increased rate at which subsequent conformational changes occur within the protein upon initial heparin binding.

For α-antithrombin, the additional glycosylation at Asn-135 is not thought to interfere with initial heparin binding, but rather to inhibit any resulting conformational changes.

[38] Antithrombin deficiency generally comes to light when a patient suffers recurrent venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Type I deficiency was originally further divided into two subgroups, Ia and Ib, based upon heparin affinity.

[46] Most cases of type I deficiency are due to point mutations, deletions or minor insertions within the antithrombin gene.

It was originally proposed that type II deficiency be further divided into three subgroups (IIa, IIb, and IIc) depending on which antithrombin functional activity is reduced or retained.

It is approved by the FDA as an anticoagulant for the prevention of clots before, during, or after surgery or birthing in patients with hereditary antithrombin deficiency.

This movement of the reactive site loop can also be induced without cleavage, with the resulting crystallographic structure being identical to that of the physiologically latent conformation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).

[61] The cleaved and latent form of antithrombin potently inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth in animal models.

[62] The prelatent form of antithrombin has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis in-vitro but to date has not been tested in experimental animal models.