Apollo 13

The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the landing was aborted after an oxygen tank in the service module (SM) exploded two days into the mission, disabling its electrical and life-support system.

There was a critical need to adapt the CM's cartridges for the carbon dioxide scrubber system to work in the LM; the crew and mission controllers were successful in improvising a solution.

[note 2][15] Even before the first U.S. astronaut entered space in 1961, planning for a centralized facility to communicate with the spacecraft and monitor its performance had begun, for the most part the brainchild of Christopher C. Kraft Jr., who became NASA's first flight director.

[33] Usually low in seniority, they assembled the mission's rules, flight plan, and checklists, and kept them updated;[34][35] for Apollo 13, they were Vance D. Brand, Jack Lousma and either William Pogue or Joseph Kerwin.

[72] Despite the crashes of one LLTV and one similar Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) prior to Apollo 13, mission commanders considered flying them invaluable experience and so prevailed on reluctant NASA management to retain them.

[93] The four outboard engines and the S-IVB third stage burned longer to compensate, and the vehicle achieved very close to the planned circular 190 kilometers (120 mi; 100 nmi) parking orbit, followed by a translunar injection (TLI) about two hours later, setting the mission on course for the Moon.

[102] Communications were enlivened when Swigert realized that in the last-minute rush, he had omitted to file his federal income tax return (due April 15), and amid laughter from mission controllers, asked how he could get an extension.

[107] The Flight Director, Kranz, had Liebergot wait a few minutes for the crew to settle down after the telecast,[109] then Lousma relayed the request to Swigert, who activated the switches controlling the fans,[107] and after a few seconds turned them off again.

[108] Ninety-five seconds after Swigert activated those switches,[109] the astronauts heard a "pretty large bang", accompanied by fluctuations in electrical power and the firing of the attitude control thrusters.

[117] Had Apollo 13's accident occurred on the return voyage, with the LM already jettisoned, the astronauts would have died,[119] as they would have following an explosion in lunar orbit, including one while Lovell and Haise walked on the Moon.

However, the accident could have damaged the SPS, and the fuel cells would have to last at least another hour to meet its power requirements, so Kranz instead decided on a longer route: the spacecraft would swing around the Moon before heading back to Earth.

Jerry Bostick and other Flight Dynamics Officers (FIDOs) were anxious both to shorten the travel time and to move splashdown to the Pacific Ocean, where the main recovery forces were located.

After a meeting involving NASA officials and engineers, the senior individual present, Manned Spaceflight Center director Robert R. Gilruth, decided on a burn using the DPS, that would save 12 hours and land Apollo 13 in the Pacific.

[128] Normally, the accuracy of such a burn could be assured by checking the alignment Lovell had transferred to the LM's computer against the position of one of the stars astronauts used for navigation, but the light glinting off the many pieces of debris accompanying the spacecraft made that impractical.

[133] The procedure for building the device was read to the crew by CAPCOM Joseph Kerwin over the course of an hour, and was built by Swigert and Haise; carbon dioxide levels began dropping immediately.

[136] The crew's ration was 0.2 liters (6.8 fl oz) of water per person per day; the three astronauts lost a total of 14 kilograms (31 lb) among them, and Haise developed a urinary tract infection.

As the LM's guidance system had been shut down following the PC+2 burn, the crew was told to use the line between night and day on the Earth to guide them, a technique used on NASA's Earth-orbit missions but never on the way back from the Moon.

They reported that an entire panel was missing from the SM's exterior, the fuel cells above the oxygen tank shelf were tilted, that the high-gain antenna was damaged, and there was a considerable amount of debris elsewhere.

Grumman, manufacturer of the LM, assigned a team of University of Toronto engineers, led by senior scientist Bernard Etkin, to solve the problem of how much air pressure to use to push the modules apart.

[119][149] Apollo 13's final midcourse correction had addressed the concerns of the Atomic Energy Commission, which wanted the cask containing the plutonium oxide intended for the SNAP-27 RTG to land in a safe place.

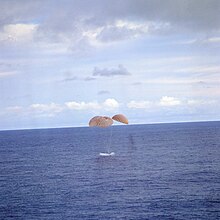

[150] Odyssey regained radio contact and splashed down safely in the South Pacific Ocean, 21°38′24″S 165°21′42″W / 21.64000°S 165.36167°W / -21.64000; -165.36167 (Apollo 13 splashdown),[151] southeast of American Samoa and 6.5 km (4.0 mi; 3.5 nmi) from the recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima.

[158] President Nixon canceled appointments, phoned the astronauts' families, and drove to NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, where Apollo's tracking and communications were coordinated.

Pope Paul VI led a congregation of 10,000 people in praying for the astronauts' safe return; ten times that number offered prayers at a religious festival in India.

Jack Gould of The New York Times stated that Apollo 13, "which came so close to tragic disaster, in all probability united the world in mutual concern more fully than another successful landing on the Moon would have".

[170] The board praised the response to the emergency: "The imperfection in Apollo 13 constituted a near disaster, averted only by outstanding performance on the part of the crew and the ground control team which supported them.

"[171] Oxygen Tank 2 was manufactured by the Beech Aircraft Company of Boulder, Colorado, as subcontractor to North American Rockwell (NAR) of Downey, California, prime contractor for the CSM.

[100] An experiment to measure the amount of atmospheric electrical phenomena during the ascent to orbit – added after Apollo 12 was struck by lightning – returned data indicating a heightened risk during marginal weather.

[204] Nevertheless, the accident convinced some officials, such as Manned Spaceflight Center director Gilruth, that if NASA kept sending astronauts on Apollo missions, some would inevitably be killed, and they called for as quick an end as possible to the program.

[204][206] The 1974 movie Houston, We've Got a Problem, while set around the Apollo 13 incident, is a fictional drama about the crises faced by ground personnel when the emergency disrupts their work schedules and places further stress on their lives.

[216] In 2020, the BBC World Service began airing 13 Minutes to the Moon, radio programs which draw on NASA audio from the mission, as well as archival and recent interviews with participants.

Nobody believes me, but during this six-day odyssey, we had no idea what an impression Apollo 13 made on the people of Earth. We never dreamed a billion people were following us on television and radio, and reading about us in banner headlines of every newspaper published. We still missed the point on board the carrier Iwo Jima , which picked us up, because the sailors had been as remote from the media as we were. Only when we reached Honolulu did we comprehend our impact: there we found President Nixon and [NASA Administrator] Dr. Paine to meet us, along with my wife Marilyn, Fred's wife Mary (who, being pregnant, also had a doctor along just in case), and bachelor Jack's parents, in lieu of his usual airline stewardesses.

— Jim Lovell [ 138 ]