Coastline paradox

Although the "paradox of length" was previously noted by Hugo Steinhaus,[1] the first systematic study of this phenomenon was by Lewis Fry Richardson,[2][3] and it was expanded upon by Benoit Mandelbrot.

Richardson had believed, based on Euclidean geometry, that a coastline would approach a fixed length, as do similar estimations of regular geometric figures.

A precise value for this length can be found using calculus, the branch of mathematics enabling the calculation of infinitesimally small distances.

The truth value of this assumption—which underlies Euclidean geometry and serves as a useful model in everyday measurement—is a matter of philosophical speculation, and may or may not reflect the changing realities of "space" and "distance" on the atomic level (approximately the scale of a nanometer).

[10] More than a decade after Richardson completed his work, Benoit Mandelbrot developed a new branch of mathematics, fractal geometry, to describe just such non-rectifiable complexes in nature as the infinite coastline.

[11] His own definition of the new figure serving as the basis for his study is:[12] I coined fractal from the Latin adjective fractus.

Mandelbrot then describes various mathematical curves, related to the Koch snowflake, which are defined in such a way that they are strictly self-similar.

Instead, it notes that Richardson's empirical law is compatible with the idea that geographic curves, such as coastlines, can be modelled by random self-similar figures of fractional dimension.

Near the end of the paper Mandelbrot briefly discusses how one might approach the study of fractal-like objects in nature that look random rather than regular.

In the hypothetical situation that a given coastline has this property of self-similarity, then no matter how great any one small section of coastline is magnified, a similar pattern of smaller bays and promontories superimposed on larger bays and promontories appears, right down to the grains of sand.

At that scale the coastline appears as a momentarily shifting, potentially infinitely long thread with a stochastic arrangement of bays and promontories formed from the small objects at hand.

In such an environment (as opposed to smooth curves) Mandelbrot asserts[11] "coastline length turns out to be an elusive notion that slips between the fingers of those who want to grasp it".

Mandelbrot's statement of the Richardson effect is:[16] where L, coastline length, a function of the measurement unit ε, is approximated by the expression.

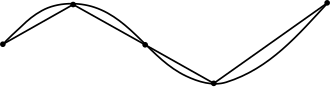

Rearranging the expression yields where Fε−D must be the number of units ε required to obtain L. The broken line measuring a coast does not extend in one direction nor does it represent an area, but is intermediate between the two and can be thought of as a band of width 2ε.

[17] The coastline paradox describes a problem with real-world applications, including trivial matters such as which river, beach, border, coastline is the longest, with the former two records a matter of fierce debate; furthermore, the problem extends to demarcating territorial boundaries, property rights, erosion monitoring, and the theoretical implications of our geometric modelling.

[18][20] The comparison to fractals, while useful as a metaphor to explain the problem, is criticized as not fully accurate, as coastlines are not self-repeating and are fundamentally finite.

Thus wide number of "shorelines" may be constructed for varied analytical purposes using different data sources and methodologies, each with a different length.