Austronesian languages

[6] In 1706, the Dutch scholar Adriaan Reland first observed similarities between the languages spoken in the Malay Archipelago and by peoples on islands in the Pacific Ocean.

[7] In the 19th century, researchers (e.g. Wilhelm von Humboldt, Herman van der Tuuk) started to apply the comparative method to the Austronesian languages.

The geographical span of Austronesian was the largest of any language family in the first half of the second millennium CE, before the spread of Indo-European in the colonial period.

[10] The canonical root type in Proto-Austronesian is disyllabic with the shape CV(C)CVC (C = consonant; V = vowel), and is still found in many Austronesian languages.

[16] Most affixes are prefixes (Malay and Indonesian ber-jalan 'walk' < jalan 'road'), with a smaller number of suffixes (Tagalog titis-án 'ashtray' < títis 'ash') and infixes (Roviana t

The word for two is also stable, in that it appears over the entire range of the Austronesian family, but the forms (e.g. Bunun dusa; Amis tusa; Māori rua) require some linguistic expertise to recognise.

The family consists of many similar and closely related languages with large numbers of dialect continua, making it difficult to recognize boundaries between branches.

In a study that represents the first lexicostatistical classification of the Austronesian languages, Isidore Dyen (1965) presented a radically different subgrouping scheme.

The Eastern Formosan peoples Basay, Kavalan, and Amis share a homeland motif that has them coming originally from an island called Sinasay or Sanasay.

The fact that the Kradai languages share the numeral system (and other lexical innovations) of pMP suggests that they are a coordinate branch with Malayo-Polynesian, rather than a sister family to Austronesian.

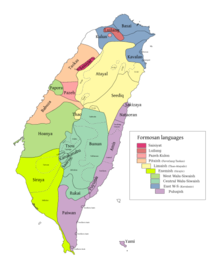

While some scholars suspect that the number of principal branches among the Formosan languages may be somewhat less than Blust's estimate of nine (e.g. Li 2006), there is little contention among linguists with this analysis and the resulting view of the origin and direction of the migration.

Archaeological evidence (e.g., Bellwood 1997) is more consistent, suggesting that the ancestors of the Austronesians spread from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan at some time around 8,000 years ago.

Evidence from historical linguistics suggests that it is from this island that seafaring peoples migrated, perhaps in distinct waves separated by millennia, to the entire region encompassed by the Austronesian languages.

The view that linguistic evidence connects Austronesian languages to the Sino-Tibetan ones, as proposed for example by Sagart (2002), is a minority one.

This homeland area may have also included the P'eng-hu (Pescadores) islands between Taiwan and China and possibly even sites on the coast of mainland China, especially if one were to view the early Austronesians as a population of related dialect communities living in scattered coastal settlements.Linguistic analysis of the Proto-Austronesian language stops at the western shores of Taiwan; any related mainland language(s) have not survived.

Ostapirat (2005) proposes a series of regular correspondences linking the two families and assumes a primary split, with Kra-Dai speakers being the people who stayed behind in their Chinese homeland.

Rather, he suggests that proto-Kra-Dai speakers were Austronesians who migrated to Hainan Island and back to the mainland from the northern Philippines, and that their distinctiveness results from radical restructuring following contact with Hmong–Mien and Sinitic.

[citation needed] Robert Blust supports the hypothesis which connects the lower Yangtze neolithic Austro-Tai entity with the rice-cultivating Austro-Asiatic cultures, assuming the center of East Asian rice domestication, and putative Austric homeland, to be located in the Yunnan/Burma border area.

[42] Under that view, there was an east-west genetic alignment, resulting from a rice-based population expansion, in the southern part of East Asia: Austroasiatic-Kra-Dai-Austronesian, with unrelated Sino-Tibetan occupying a more northerly tier.

[43] Sagart argues for a north-south genetic relationship between Chinese and Austronesian, based on sound correspondences in the basic vocabulary and morphological parallels.

[42] Laurent Sagart (2017) concludes that the possession of the two kinds of millets[a] in Taiwanese Austronesian languages (not just Setaria, as previously thought) places the pre-Austronesians in northeastern China, adjacent to the probable Sino-Tibetan homeland.

[42] Ko et al.'s genetic research (2014) appears to support Laurent Sagart's linguistic proposal, pointing out that the exclusively Austronesian mtDNA E-haplogroup and the largely Sino-Tibetan M9a haplogroup are twin sisters, indicative of an intimate connection between the early Austronesian and Sino-Tibetan maternal gene pools, at least.

[44][45] Additionally, results from Wei et al. (2017) are also in agreement with Sagart's proposal, in which their analyses show that the predominantly Austronesian Y-DNA haplogroup O3a2b*-P164(xM134) belongs to a newly defined haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 being widely distributed along the eastern coastal regions of Asia, from Korea to Vietnam.

[46] Sagart also groups the Austronesian languages in a recursive-like fashion, placing Kra-Dai as a sister branch of Malayo-Polynesian.

The linguist Ann Kumar (2009) proposed that some Austronesians might have migrated to Japan, possibly an elite-group from Java, and created the Japanese-hierarchical society.

Robert Blust rejects Blevins' proposal as far-fetched and based solely on chance resemblances and methodologically flawed comparisons.

Below are two charts comparing list of numbers of 1–10 and thirteen words in Austronesian languages; spoken in Taiwan, the Philippines, the Mariana Islands, Indonesia, Malaysia, Chams or Champa (in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam), East Timor, Papua, New Zealand, Hawaii, Madagascar, Borneo, Kiribati, Caroline Islands, and Tuvalu.