Archosaur

Modern paleontologists define Archosauria as a crown group that includes the most recent common ancestor of living birds and crocodilians, and all of its descendants.

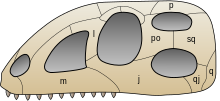

[4] Older definitions of the group Archosauria rely on shared morphological characteristics, such as an antorbital fenestra in the skull, serrated teeth, and an upright stance.

Some extinct reptiles, such as proterosuchids and euparkeriids, also possessed these features yet originated prior to the split between the crocodilian and bird lineages.

The older morphological definition of Archosauria nowadays roughly corresponds to Archosauriformes, a group named to encompass crown-group archosaurs and their close relatives.

Archosaurs quickly diversified in the aftermath of the Permian-Triassic mass extinction (~252 Ma), which wiped out most of the then-dominant therapsid competitors such as the gorgonopsians and anomodonts, and the subsequent arid Triassic climate allowed the more drought-resilient archosaurs (largely due to their uric acid-based urinary system) to eventually become the largest and most ecologically dominant terrestrial vertebrates from the Middle Triassic period up until the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (~66 Ma).

Many of these characteristics appeared prior to the origin of the clade Archosauria, as they were present in archosauriforms such as Proterosuchus and Euparkeria, which were outside the crown group.

[4] The most obvious features include teeth set in deep sockets, antorbital and mandibular fenestrae (openings in front of the eyes and in the jaw, respectively),[6] and a pronounced fourth trochanter (a prominent ridge on the femur).

This feature is responsible for the name "thecodont" (meaning "socket teeth"),[8] which early paleontologists applied to many Triassic archosaurs.

Very few large synapsids survived the event, but one form, Lystrosaurus (a herbivorous dicynodont), attained a widespread distribution soon after the extinction.

[13] Suggested explanations for this include: However, this theory has been questioned, since it implies synapsids were necessarily less advantaged in water retention, that synapsid decline coincides with climate changes or archosaur diversity (neither of which tested) and the fact that desert dwelling mammals are as well adapted in this department as archosaurs,[15] and some cynodonts like Trucidocynodon were large sized predators.

[18] The earliest archosaurs had "primitive mesotarsal" ankles: the astragalus and calcaneum were fixed to the tibia and fibula by sutures and the joint bent about the contact between these bones and the foot.

The archosaurian fourth trochanter on the femur may have made it easier for ornithodirans to become bipeds, because it provided more leverage for the thigh muscles.

Archosauria is normally defined as a crown group, which means that it only includes descendants of the last common ancestors of its living representatives.

While many researchers prefer to treat Archosauria as an unranked clade, some continue to assign it a traditional biological rank.

Traditionally, Archosauria has been treated as a Superorder, though a few 21st century researchers have assigned it to different ranks including Division[21] and Class.

Because they are considered a "basal stock", thecodonts are paraphyletic, meaning that they form a group that does not include all descendants of its last common ancestor: in this case, the more derived crocodilians and birds are excluded from "Thecodontia" as it was formerly understood.

The description of the basal ornithodires Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus in the 1970s provided evidence that linked thecodonts with dinosaurs, and contributed to the disuse of the term "Thecodontia", which many cladists consider an artificial grouping.

Cruickshank identified the basal split and thought that the crurotarsan ankle developed independently in these two groups, but in opposite ways.

Below is the cladogram from Gauthier (1986):[27] †Proterosuchidae †Erythrosuchidae †Proterochampsidae †Parasuchia †Aetosauria †Rauisuchia Crocodylomorpha †Euparkeria †Ornithosuchidae Ornithodira In 1988, paleontologists Michael Benton and J. M. Clark produced a new tree in a phylogenetic study of basal archosaurs.

Unlike Gauthier's tree, Benton and Clark's places Euparkeria outside Ornithosuchia and outside the crown group Archosauria altogether.

Below is a cladogram modified from Benton (2004) showing this phylogeny:[24] †Hyperodapedon (Rhynchosauria) †Prolacerta (Prolacertiformes) †Proterosuchus (Proterosuchidae) †Euparkeria (Euparkeriidae) †Proterochampsidae †Phytosauridae †Gracilisuchus †Ornithosuchidae †Stagonolepididae †Postosuchus Crocodylomorpha †Fasolasuchus †Ticinosuchus †Prestosuchus †Saurosuchus †Scleromochlus †Pterosauria †Lagerpeton †Marasuchus †Ornithischia †Sauropodomorpha †Herrerasaurus Neotheropoda In Sterling Nesbitt's 2011 monograph on early archosaurs, a phylogenetic analysis found strong support for phytosaurs falling outside Archosauria.

In the early to middle Triassic, some archosaur groups developed hip joints that allowed (or required) a more erect gait.

But crocodilians have some features which are normally associated with a warm-blooded metabolism because they improve the animal's oxygen supply: Historically there has been uncertainty as to why natural selection favored the development of these features, which are very important for active warm-blooded creatures, but of little apparent use to cold-blooded aquatic ambush predators that spend the vast majority of their time floating in water or lying on river banks.

[33] Physiological, anatomical, and developmental features of the crocodilian heart support the paleontological evidence and show that the lineage reverted to ectothermy when it invaded the aquatic, ambush predator niche.

The researchers concluded that the ancestors of living crocodilians had fully 4-chambered hearts, and were therefore warm-blooded, before they reverted to a cold-blooded or ectothermic metabolism.

Unidirectional airflow in both birds and alligators suggests that this type of respiration was present at the base of Archosauria and retained by both dinosaurs and non-dinosaurian archosaurs, such as aetosaurs, "rauisuchians" (non-crocodylomorph paracrocodylomorphs), crocodylomorphs, and pterosaurs.

The better efficiency in gas transfer seen in archosaur lungs may have been advantageous during the times of low atmospheric oxygen which are thought to have existed during the Mesozoic.

The pelvic anatomy of Cricosaurus and other metriorhynchids[41] and fossilized embryos belonging to the non-archosaur archosauromorph Dinocephalosaurus,[42] together suggest that the lack of viviparity among archosaurs may be a consequence of lineage-specific restrictions.

The notable exception are Neornithes which incubate their eggs and rely on genetic sex determination – a trait that might have given them a survival advantage over other dinosaurs.