Arctic exploration

Historical records suggest that humankind have explored the northern extremes since 325 BC, when the ancient Greek sailor Pytheas reached a frozen sea while attempting to find a source of the metal tin.

[1] Dangerous oceans and poor weather conditions often fetter explorers attempting to reach polar regions, and journeying through these perils by sight, boat, and foot has proven difficult.

[2] The theory was originally put forth by William F. Warren, the first President of Boston University, in his Paradise Found or the Cradle of the Human Race at the North Pole.

Scholar James D. P. Bolton instead located the Issedones people on the south-western slopes of the Altay mountains, which led his colleague Carl P. Ruck to place Hyperborea beyond the Dzungarian Gate into the northern part of the Xinjiang region, adding that the Hyperboreans were probably Chinese.

Some historians claim that this new land of Thule was either the Norwegian coast or the Shetland Islands based on his descriptions and the trade routes of early British sailors.

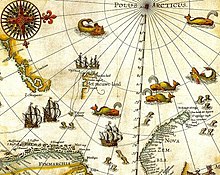

Exploration to the north of the Arctic Circle in the Renaissance was both driven by the rediscovery of the Classics and the national quests for commercial expansion, and hampered by limits in maritime technology, lack of stable food supplies, and insufficient insulation for the crew against extreme cold.

A seminal event in Arctic exploration occurred in 1409, when Ptolemy's Geographia was translated into Latin, thereby introducing the concepts of latitude and longitude into Western Europe.

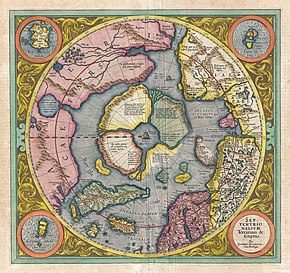

The Inventio Fortunata, a lost book, describes in a summary written by Jacobus Cnoyen but only found in a letter from Gerardus Mercator, voyages as far as the North Pole.

[16] One widely disputed claim is that two brothers from Venice, Niccolo and Antonio Zeno, allegedly made a map of their journeys to that region, which were published by their descendants in 1558.

Since the discovery of the American continent was the product of the search for a route to Asia, exploration around the northern edge of North America continued for the Northwest Passage.

John Cabot's initial failure in 1497 to find a Northwest Passage across the Atlantic led the British to seek an alternative route to the east.

In July 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who had written a treatise on the discovery of the passage and was a backer of Frobisher's, claimed the territory of Newfoundland for the English crown.

Though he was unable to pass through the icy Arctic waters, he reported to his sponsors that the passage they sought is "a matter nothing doubtfull [sic],"[18] and secured support for two additional expeditions, reaching as far as Hudson Bay.

Though England's efforts were interrupted in 1587 because of the Anglo-Spanish War, Davis's favorable reports on the region and its people would inspire explorers in the coming century.

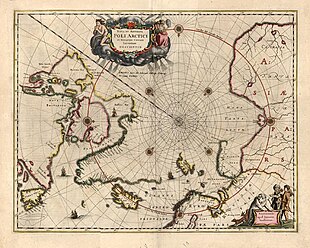

[20][21] The Northeast Passage is a broad term for any route lying above the Eurasian continent and stretching between the waters north of the Norwegian Sea to the Bering Strait.

[22] In the mid-16th century, John Cabot's son Sebastian helped organize just such an expedition, led by Sir Hugh Willoughby and Richard Chancellor.

Some years later, Steven Borough, the master of Chancellor's ship, made it as far as the Kara Sea, when he was forced to turn back because of icy conditions.

[23] Western parts of the passage were simultaneously being explored by Northern European countries like England, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway, looking for an alternative seaway to China and India.

Pomor activity in Northern Asia declined and the bulk of exploration in the 17th century was carried out by Siberian Cossacks, sailing from one river mouth to another in their Arctic-worthy kochs.

In 1648 the most famous of these expeditions, led by Fedot Alekseev and Semyon Dezhnev, sailed east from the mouth of Kolyma to the Pacific and doubled the Chukchi Peninsula, thus proving that there was no land connection between Asia and North America.

Rae used a pragmatic approach of traveling by land on foot and dog sled, and typically employed less than ten people in his exploration parties.

In 1969 Wally Herbert, on foot and by dog sled, became the first man to reach the North Pole on muscle power alone, on the 60th anniversary of Robert Peary's famous but disputed expedition.

The first persons to reach the North Pole on foot (or skis) and return with no outside help, no dogs, airplanes, or re-supplies were Richard Weber (Canada) and Misha Malakhov (Russia) in 1995.

Georg von Rosen (1886)