History of cartography

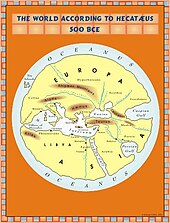

The Greeks believed that they occupied the central region of Earth and its edges were inhabited by savage, monstrous barbarians and strange animals and monsters: Homer's Odyssey mentions a great many of these.

Ptolemy revolutionized the depiction of the spherical Earth on a map by using perspective projection, and suggested precise methods for fixing the position of geographic features on its surface using a coordinate system with parallels of latitude and meridians of longitude.

It included an index of place-names, with the latitude and longitude of each place to guide the search, scale, conventional signs with legends, and the practice of orienting maps so that north is at the top and east to the right of the map—an almost universal custom today.

[43]: 536 From the 1st century AD onwards, official Chinese historical texts contained a geographical section (地理纪; Diliji), which was often an enormous compilation of changes in place-names and local administrative divisions controlled by the ruling dynasty, descriptions of mountain ranges, river systems, taxable products, etc.

The chapter gave general descriptions of topography in a systematic fashion, given visual aids by the use of maps (di tu) due to the efforts of Liu An and his associate Zuo Wu.

[43]: 543 In 610 Emperor Yang of Sui ordered government officials from throughout the empire to document in gazetteers the customs, products, and geographical features of their local areas and provinces, providing descriptive writing and drawing them all onto separate maps, which would be sent to the imperial secretariat in the capital city.

In pursuance of his schemes for the relief of famines he issued orders that each pao (village) should prepare a map which would show the fields and mountains, the rivers and the roads in fullest detail.

If there was any trouble about the collection of taxes or the distribution of grain, or if the question of chasing robbers and bandits arose, the provincial officials could readily carry out their duties by the aid of the maps.

[49] Shen also created a three-dimensional raised-relief map using sawdust, wood, beeswax, and wheat paste, while representing the topography and specific locations of a frontier region to the imperial court.

[64] In 1579, Luo Hongxian published the Guang Yutu atlas, including more than 40 maps, a grid system, and a systematic way of representing major landmarks such as mountains, rivers, roads and borders.

Gridlines are not used on either Yu Shi's Gujin xingsheng zhi tu (1555) or Zhang Huang's Tushu bian (1613); instead, illustrations and annotations show mythical places, exotic foreign peoples, administrative changes and the deeds of historic and legendary heroes.

The earliest surviving world maps based on a rectangular coordinate grid are attributed to al-Mustawfi in the 14th or 15th century (who used invervals of ten degrees for the lines), and to Hafiz-i Abru (died 1430).

[74]: 188 Other prime meridians used were set by Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī and Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi at Ujjain, a centre of Indian astronomy, and by another anonymous writer at Basra.

[81][82][83] Al-Biruni's method's motivation was to avoid "walking across hot, dusty deserts" and the idea came to him when he was on top of a tall mountain in India (present day Pind Dadan Khan, Pakistan).

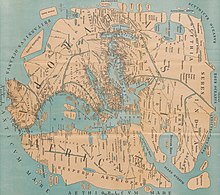

He incorporated the knowledge of Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East gathered by Arab merchants and explorers with the information inherited from the classical geographers to create the most accurate map of the world in pre-modern times.

Known as Mappa Mundi (cloths or charts of the world) these maps were circular or symmetrical cosmological diagrams representing the Earth's single land mass as disk-shaped and surrounded by ocean.

Jordan Branch and his advisor, Steven Weber, propose that the power of large kingdoms and nation states of later history are an inadvertent byproduct of 15th-century advances in map-making technologies.

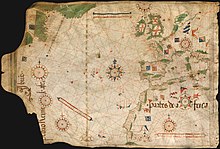

Portugal's methodical expeditions started in 1419 along West Africa's coast under the sponsorship of Prince Henry the Navigator, with Bartolomeu Dias reaching the Cape of Good Hope and entering the Indian Ocean in 1488.

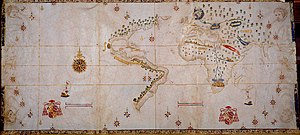

Soon, after Pedro Álvares Cabral reaching Brazil (1500), explorations proceed to Southeast Asia, having sent the first direct European maritime trade and diplomatic missions to Ming China and to Japan (1542).

It was a Spanish expedition that sailed from Seville in 1519 under the command of Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan in search of a maritime path from the Americas to the East Asia across the Pacific Ocean.

Following Magellan's death in Mactan (Philippines) in 1521, Juan Sebastián Elcano took command of the expedition, sailing to Borneo, the Spice Islands and back to Spain across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope and north along the west coast of Africa.

The originals of the Spanish and Portuguese maps are now lost but copies of known provenance are held by the Vatican Library; the Biblioteca Estense in Modena, Italy; and the Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar, Germany.

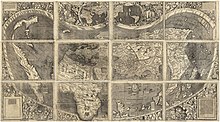

[104] Incorporating information from the Magellan, Gómez, and Loaysa expeditions and the geodesic research undertaken to codify the demarcation lines established by the treaties of Tordesillas and Zaragoza, these editions of the Padrón Real show for the first time the full extension of the Pacific Ocean and the continuous coast of North America.

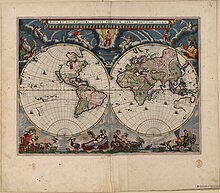

Mercator's insight was to stretch the separation of the parallels in a way which exactly compensates for their increasing length, thus preserving shapes of small regions, albeit at the expense of global distortion.

That this was Mercator's intention is clear from the title: Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata which translates as "New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation".

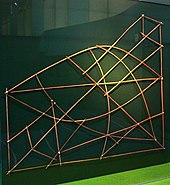

[108] Triangulation had first emerged as a map making method in the early 16th century when Gemma Frisius set out the idea in his Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (Booklet concerning a way of describing places).

He noted five distinct reasons: 1) admiration of antiquity, especially the rediscovery of Ptolemy, considered to be the first geographer; 2) increasing reliance on measurement and quantification as a result of the scientific revolution; 3) refinements in the visual arts, such as the discovery of perspective, that allowed for better representation of spatial entities; 4) development of estate property; and 5) the importance of mapping to nation-building.

"[121][page needed] Because unification of the kingdom necessitated well-kept records of land and tax bases, Louis XIV and members of the royal court pushed the development and progression of the sciences, especially cartography.

[123] Cassini, along with the aid and support of mathematician Jean Picard, developed a system of uniting the provincial topographical information into a comprehensive map of the country, through a network of surveyed triangles.

Aerial photography and satellite imagery have provided high-accuracy, high-throughput methods for mapping physical features over large areas, such as coastlines, roads, buildings, and topography.