Area of a circle

Here, the Greek letter π represents the constant ratio of the circumference of any circle to its diameter, approximately equal to 3.14159.

One method of deriving this formula, which originated with Archimedes, involves viewing the circle as the limit of a sequence of regular polygons with an increasing number of sides.

Modern mathematics can obtain the area using the methods of integral calculus or its more sophisticated offspring, real analysis.

The original proof of Archimedes is not rigorous by modern standards, because it assumes that we can compare the length of arc of a circle to the length of a secant and a tangent line, and similar statements about the area, as geometrically evident.

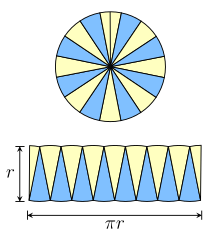

This suggests that the area of a disk is half the circumference of its bounding circle times the radius.

Draw a perpendicular from the center to the midpoint of a side of the polygon; its length, h, is less than the circle radius.

For, a perpendicular to the midpoint of each polygon side is a radius, of length r. And since the total side length is greater than the circumference, the polygon consists of n identical triangles with total area greater than T. Again we have a contradiction, so our supposition that C might be less than T must be wrong as well.

130–132), Nicholas of Cusa[4] and Leonardo da Vinci (Beckmann 1976, p. 19), we can use inscribed regular polygons in a different way.

Two opposite triangles both touch two common diameters; slide them along one so the radial edges are adjacent.

For a polygon with 2n sides, the parallelogram will have a base of length ns, and a height h. As the number of sides increases, the length of the parallelogram base approaches half the circle circumference, and its height approaches the circle radius.

In the limit, the parallelogram becomes a rectangle with width πr and height r. There are various equivalent definitions of the constant π.

, but in many cases to regard these as actual proofs, they rely implicitly on the fact that one can develop trigonometric functions and the fundamental constant π in a way that is totally independent of their relation to geometry.

We have indicated where appropriate how each of these proofs can be made totally independent of all trigonometry, but in some cases that requires more sophisticated mathematical ideas than those afforded by elementary calculus.

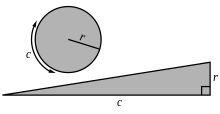

Using calculus, we can sum the area incrementally, partitioning the disk into thin concentric rings like the layers of an onion.

This gives an elementary integral for a disk of radius r. It is rigorously justified by the multivariate substitution rule in polar coordinates.

If D denotes the disk, then the double integral can be computed in polar coordinates as follows: which is the same result as obtained above.

An equivalent rigorous justification, without relying on the special coordinates of trigonometry, uses the coarea formula.

This will form a right angled triangle with r as its height and 2πr (being the outer slice of onion) as its base.

is just the arc length, which is its circumference, so this shows that the area A enclosed by the circle is equal to

This particular proof may appear to beg the question, if the sine and cosine functions involved in the trigonometric substitution are regarded as being defined in relation to circles.

However, as noted earlier, it is possible to define sine, cosine, and π in a way that is totally independent of trigonometry, in which case the proof is valid by the change of variables formula and Fubini's theorem, assuming the basic properties of sine and cosine (which can also be proved without assuming anything about their relation to circles).

The calculations Archimedes used to approximate the area numerically were laborious, and he stopped with a polygon of 96 sides.

A faster method uses ideas of Willebrord Snell (Cyclometricus, 1621), further developed by Christiaan Huygens (De Circuli Magnitudine Inventa, 1654), described in Gerretsen & Verdenduin (1983, pp. 243–250).

The number 355⁄113 is also an excellent approximation to π, attributed to Chinese mathematician Zu Chongzhi, who named it Milü.

Let one side of an inscribed regular n-gon have length sn and touch the circle at points A and B.

The center of the circle, O, bisects A′A, so we also have triangle OAP similar to A′AB, with OP half the length of A′B.

For a unit circle we have the famous doubling equation of Ludolph van Ceulen, If we now circumscribe a regular n-gon, with side A″B″ parallel to AB, then OAB and OA″B″ are similar triangles, with A″B″ : AB = OC : OP.

The hyperbolic case is similar, with the area of a disk of intrinsic radius R in the (constant curvature

It is more generally true that the area of the circle of a fixed radius R is a strictly decreasing function of the curvature.

is the curvature (constant, positive or negative), then the isoperimetric inequality for a domain with area A and perimeter L is where equality is achieved precisely for the circle.