Area of a triangle

In geometry, calculating the area of a triangle is an elementary problem encountered often in many different situations.

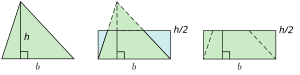

Euclid proved that the area of a triangle is half that of a parallelogram with the same base and height in his book Elements in 300 BCE.

[1] In 499 CE Aryabhata, used this illustrated method in the Aryabhatiya (section 2.6).

[2] Although simple, this formula is only useful if the height can be readily found, which is not always the case.

For example, the land surveyor of a triangular field might find it relatively easy to measure the length of each side, but relatively difficult to construct a 'height'.

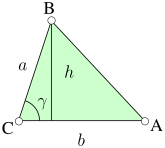

Other frequently used formulas for the area of a triangle use trigonometry, side lengths (Heron's formula), vectors, coordinates, line integrals, Pick's theorem, or other properties.

[3] Heron of Alexandria found what is known as Heron's formula for the area of a triangle in terms of its sides, and a proof can be found in his book, Metrica, written around 60 CE.

It has been suggested that Archimedes knew the formula over two centuries earlier,[4] and since Metrica is a collection of the mathematical knowledge available in the ancient world, it is possible that the formula predates the reference given in that work.

[5] In 300 BCE Greek mathematician Euclid proved that the area of a triangle is half that of a parallelogram with the same base and height in his book Elements of Geometry.

[6] In 499 Aryabhata, a great mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, expressed the area of a triangle as one-half the base times the height in the Aryabhatiya.

[7] A formula equivalent to Heron's was discovered by the Chinese independently of the Greeks.

It was published in 1247 in Shushu Jiuzhang ("Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections"), written by Qin Jiushao.

First, denoting the medians from sides a, b, and c respectively as ma, mb, and mc and their semi-sum (ma + mb + mc)/2 as σ, we have[10] Next, denoting the altitudes from sides a, b, and c respectively as ha, hb, and hc, and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as

are vectors to the triangle's vertices from any arbitrary origin point, so that

The oriented relative area of a parallelogram in any affine space, a type of bivector, is defined as

are translation vectors from one vertex of the parallelogram to each of the two adjacent vertices.

In Euclidean space, the magnitude of this bivector is a well-defined scalar number representing the area of the parallelogram.

The area of triangle ABC can also be expressed in terms of dot products.

[13] This area formula can be derived from the previous one using the elementary vector identity

If vertex A is located at the origin (0, 0) of a Cartesian coordinate system and the coordinates of the other two vertices are given by B = (xB, yB) and C = (xC, yC), then the area can be computed as 1⁄2 times the absolute value of the determinant For three general vertices, the equation is: which can be written as If the points are labeled sequentially in the counterclockwise direction, the above determinant expressions are positive and the absolute value signs can be omitted.

If we locate the vertices in the complex plane and denote them in counterclockwise sequence as a = xA + yAi, b = xB + yBi, and c = xC + yCi, and denote their complex conjugates as

In three dimensions, the area of a general triangle A = (xA, yA, zA), B = (xB, yB, zB) and C = (xC, yC, zC) is the Pythagorean sum of the areas of the respective projections on the three principal planes (i.e. x = 0, y = 0 and z = 0): The area within any closed curve, such as a triangle, is given by the line integral around the curve of the algebraic or signed distance of a point on the curve from an arbitrary oriented straight line L. Points to the right of L as oriented are taken to be at negative distance from L, while the weight for the integral is taken to be the component of arc length parallel to L rather than arc length itself.

This method is well suited to computation of the area of an arbitrary polygon.

Taking L to be the x-axis, the line integral between consecutive vertices (xi,yi) and (xi+1,yi+1) is given by the base times the mean height, namely (xi+1 − xi)(yi + yi+1)/2.

The area of a triangle then falls out as the case of a polygon with three sides.

While the line integral method has in common with other coordinate-based methods the arbitrary choice of a coordinate system, unlike the others it makes no arbitrary choice of vertex of the triangle as origin or of side as base.

Furthermore, the choice of coordinate system defined by L commits to only two degrees of freedom rather than the usual three, since the weight is a local distance (e.g. xi+1 − xi in the above) whence the method does not require choosing an axis normal to L. When working in polar coordinates it is not necessary to convert to Cartesian coordinates to use line integration, since the line integral between consecutive vertices (ri,θi) and (ri+1,θi+1) of a polygon is given directly by riri+1sin(θi+1 − θi)/2.

This is valid for all values of θ, with some decrease in numerical accuracy when |θ| is many orders of magnitude greater than π.

With this formulation negative area indicates clockwise traversal, which should be kept in mind when mixing polar and cartesian coordinates.

[20][21]: 657 Other upper bounds on the area T are given by[22]: p.290 and both again holding if and only if the triangle is equilateral.