Hyperbolic geometry

Saddle surfaces have negative Gaussian curvature in at least some regions, where they locally resemble the hyperbolic plane.

The hyperboloid model of hyperbolic geometry provides a representation of events one temporal unit into the future in Minkowski space, the basis of special relativity.

In the former Soviet Union, it is commonly called Lobachevskian geometry, named after one of its discoverers, the Russian geometer Nikolai Lobachevsky.

There are also infinitely many uniform tilings that cannot be generated from Schwarz triangles, some for example requiring quadrilaterals as fundamental domains.

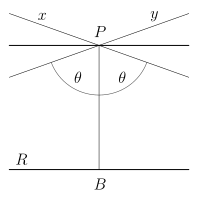

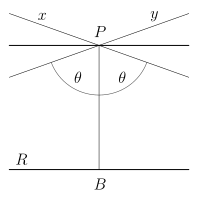

All are based around choosing a point (the origin) on a chosen directed line (the x-axis) and after that many choices exist.

In this coordinate system, straight lines take one of these forms ((x, y) is a point on the line; x0, y0, A, and α are parameters): ultraparallel to the x-axis asymptotically parallel on the negative side asymptotically parallel on the positive side intersecting perpendicularly intersecting at an angle α Generally, these equations will only hold in a bounded domain (of x values).

Foremost among these were Proclus, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen), Omar Khayyám,[6] Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, Witelo, Gersonides, Alfonso, and later Giovanni Gerolamo Saccheri, John Wallis, Johann Heinrich Lambert, and Legendre.

Their works on hyperbolic geometry had a considerable influence on its development among later European geometers, including Witelo, Gersonides, Alfonso, John Wallis and Saccheri.

[10] In the 19th century, hyperbolic geometry was explored extensively by Nikolai Lobachevsky, János Bolyai, Carl Friedrich Gauss and Franz Taurinus.

Kant in Critique of Pure Reason concluded that space (in Euclidean geometry) and time are not discovered by humans as objective features of the world, but are part of an unavoidable systematic framework for organizing our experiences.

[16] It is said that Gauss did not publish anything about hyperbolic geometry out of fear of the "uproar of the Boeotians" (stereotyped as dullards by the ancient Athenians[17]), which would ruin his status as princeps mathematicorum (Latin, "the Prince of Mathematicians").

[18] The "uproar of the Boeotians" came and went, and gave an impetus to great improvements in mathematical rigour, analytical philosophy and logic.

He realized that his measurements were not precise enough to give a definite answer, but he did reach the conclusion that if the geometry of the universe is hyperbolic, then the absolute length is at least one million times the diameter of Earth's orbit (2000000 AU, 10 parsec).

The problem in determining which one applies is that, to reach a definitive answer, we need to be able to look at extremely large shapes – much larger than anything on Earth or perhaps even in our galaxy.

[27] There exist various pseudospheres in Euclidean space that have a finite area of constant negative Gaussian curvature.

[28] In 2000, Keith Henderson demonstrated a quick-to-make paper model dubbed the "hyperbolic soccerball" (more precisely, a truncated order-7 triangular tiling).

[29][30] Instructions on how to make a hyperbolic quilt, designed by Helaman Ferguson,[31] have been made available by Jeff Weeks.

[32] Various pseudospheres – surfaces with constant negative Gaussian curvature – can be embedded in 3-D space under the standard Euclidean metric, and so can be made into tangible models.

For higher dimensions this model uses the interior of the unit ball, and the chords of this n-ball are the hyperbolic lines.

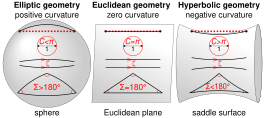

The characteristic feature of the hyperbolic plane itself is that it has a constant negative Gaussian curvature, which is indifferent to the coordinate chart used.

In 1966 David Gans proposed a flattened hyperboloid model in the journal American Mathematical Monthly.

It is also possible to see quite plainly the negative curvature of the hyperbolic plane, through its effect on the sum of angles in triangles and squares.

In Circle Limit III, for example, one can see that the number of fishes within a distance of n from the center rises exponentially.

In small dimensions, there are exceptional isomorphisms of Lie groups that yield additional ways to consider symmetries of hyperbolic spaces.

"Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam and al-Tūsī, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry whose importance came to be completely recognized only in the 19th century.

In essence their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangles which they considered assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse, embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries.

By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investigations of their European counterparts.

The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines – made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the 13th century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir) – was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources.

The proofs put forward in the 14th century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration.

Above, we have demonstrated that Pseudo-Tusi's Exposition of Euclid had stimulated both J. Wallis's and G. Saccheri's studies of the theory of parallel lines."