Argentine wine

[3][4][5][6] During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, vine cuttings were brought to Santiago del Estero in 1557, and the cultivation of the grape and wine production stretched first to neighboring regions, and then to other parts of the country.

The devaluation of the Argentine peso in 2002 further fueled the industry as production costs decreased and tourism significantly increased, giving way to a whole new concept of enotourism in Argentina.

During this time the missionaries and settlers in the area began construction of complex irrigation channels and dams that would bring water down from the melting glaciers of the Andes to sustain vineyards and agriculture.

[14] A provincial governor, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, instructed the French agronomist Miguel Aimé Pouget to bring grapevine cuttings from France to Argentina.

The ensuing global Great Depression dramatically reduced vital export revenues and foreign investment and led to a decline in the wine industry.

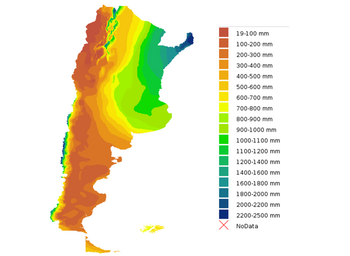

[10] The major wine regions of Argentina are located in the western part of the country among the foothills of the Andes Mountains between the Tropic of Capricorn to the north and the 40th parallel south.

Wintertime temperatures can drop below 0 °C (32 °F) but frost is a rare occurrence for most vineyards, except those planted at extremely high altitudes with poor air circulation.

[10] The northwestern wine regions are particularly prone to the effects of the hurricane force winds known as the Zonda which blows from the Andes during the flowering period of early summer.

As the winter snows start to melt in the spring, an intricate irrigation system of dams, canals and channels brings vital water supplies down to the wine regions to sustain viticulture in the dry, arid climates.

After harvest, grapes often have to be transported long distances, taking several hours, from the rural vineyards to winemaking facilities located in more urban areas.

[10] As the Argentine wine industry continues to grow in the 21st century, several related viticultural trends will involve improvements in irrigation, yield control, canopy management and the construction of more winemaking facilities closer to the vineyards.

The relative isolation of Argentina is also cited as a potential benefit against phylloxera with the country's wine regions being bordered by mountains, deserts and oceans that create natural barriers against the spread of the louse.

[12] This style was conducive to the high yielding varieties of Criolla and Cereza that were the backbone of the bulk wine production industry that arose in response to the large domestic market.

In the late 20th century, as the market turned to focus more on premium wine production, more producers switched back to the traditional espaldera system and began to practice canopy management in order to control yields.

[14] The intricate irrigation system used to bring water from melted snow caps in the Andes originated in the 16th century (with the Spanish settlers adopting techniques previously used by the Incas[10]) and has been a vital component of agriculture in Argentina.

While this method may have been an unwittingly preventive measure against the advance of phylloxera, it does not provide much control for the vineyard manager to limit yields and increase potential quality in the wine grapes.

In the southern region of Patagonia, the Río Negro and Neuquén provinces have traditionally been the fruit producing centers of the country but have recently seen growth in the planting of cool climate varietals (such as Pinot noir and Chardonnay).

The soil of the region is sandy and alluvial on top of clay substructures and the climate is continental with four distinct seasons that affect the grapevine, including winter dormancy.

The climate of this region is considerably hotter and drier than Mendoza with rainfall averaging 150 mm (6 in) a year and summer time temperatures regularly hitting 42 °C (108 °F).

[14] Recently, the higher-altitude vines planted in the Pedernal valley in Western San Juan, one of the most isolated regions in Argentina, have received significant acclaim for their potential to bring fame to the province's wine industry.

The altitude here exceeds that of more southerly Uco Valley in Mendoza, leading to extremely dry conditions with high thermal amplitude and excellent results both for red and white wines.

[29] The soils and climate of the regions are very similar to Mendoza but the unique mesoclimate and high elevation of the vineyards typically produces grapes with higher levels of total acidity which contribute to the wines balance and depth.

[31] Argentine winemakers have long held the belief that vines required hot and arid climates with large temperature variations to produce quality wines.

[citation needed] However, in the last decade, the potential for 'non-traditional' (or re-discovered) regions has become apparent, concentrated in several areas: (1) the Atlantic coast from Mar del Plata (Buenos Aires) south and including the hills in Southern Buenos Aires, and (2) the mountains in Cordoba Province, which had been significant growers in colonial times, but where winemakers have only recently started experimenting with higher altitudes, (3) Entre Rios, an unlikely location because of its humid, warm climate, which had been famous for its wines more than a century ago, and (4) the Patagonian Plateau, a region of cold, windy and arid climates.

[citation needed] The climate in Mar del Plata and along the coast of Buenos Aires Province display the same temperature range as Bordeaux with similar (high) precipitation.

Weather records suggest that the coast should be adequate for wine making much further south: into Viedma, San Antonio Oeste, Puerto Madryn, Trelew and even Comodoro Rivadavia where cool, windy desert climates are greatly moderated by the Atlantic.

Over the last decade, however, boutique wineries have discovered the potential of the exceptional variety of soils and micro-climates in the area, producing wines that have won significant national awards (some near La Cumbrecita, an alpine town that would have been considered too cool for vines recently).

[39] The scale of production remains minimal, but large numbers of new producers are experimenting with grape varieties and techniques to make wines that are significantly different from the stereotypical Mendoza Malbecs, often with great success.

[14] These varieties are often used today for bulk jug wine sold in 1 liter cardboard cartons or as grape concentrate which is exported worldwide with Japan being a considerably large market.

The international variety of Cabernet Sauvignon is gaining in popularity and beside being made as a varietal, it used as a blending partner with Malbec, Merlot, Syrah and Pinot noir.