Aristotle

Shortly after Plato died, Aristotle left Athens and, at the request of Philip II of Macedon, tutored his son Alexander the Great beginning in 343 BC.

The influence of his physical science extended from late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and was not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics were developed.

[14] The traditional story about his departure records that he was disappointed with the academy's direction after control passed to Plato's nephew Speusippus, although it is possible that the anti-Macedonian sentiments in Athens could have also influenced his decision.

He often lectured small groups of distinguished students and, along with some of them, such as Theophrastus, Eudemus, and Aristoxenus, Aristotle built a large library which included manuscripts, maps, and museum objects.

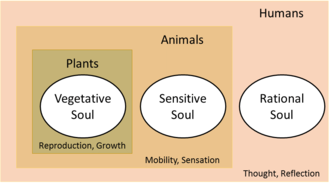

Aristotle studied and made significant contributions to "logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance, and theatre.

"[35] While Alexander deeply admired Aristotle, near the end of his life, the two men became estranged having diverging opinions over issues, like the optimal administration of city-states, the treatment of conquered populations, such as the Persians, and philosophical questions, like the definition of braveness.

In 322 BC, Demophilus and Eurymedon the Hierophant reportedly denounced Aristotle for impiety,[38] prompting him to flee to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, Euboea, at which occasion he was said to have stated "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy"[39] – a reference to Athens's trial and execution of Socrates.

[61] In his On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle related each of the four elements proposed earlier by Empedocles, earth, water, air, and fire, to two of the four sensible qualities, hot, cold, wet, and dry.

[61] A contrary opinion is given by Carlo Rovelli, who argues that Aristotle's physics of motion is correct within its domain of validity, that of objects in the Earth's gravitational field immersed in a fluid such as air.

[65][N] Newton's "forced" motion corresponds to Aristotle's "violent" motion with its external agent, but Aristotle's assumption that the agent's effect stops immediately it stops acting (e.g., the ball leaves the thrower's hand) has awkward consequences: he has to suppose that surrounding fluid helps to push the ball along to make it continue to rise even though the hand is no longer acting on it, resulting in the Medieval theory of impetus.

[77][78] The geologist Charles Lyell noted that Aristotle described such change, including "lakes that had dried up" and "deserts that had become watered by rivers", giving as examples the growth of the Nile delta since the time of Homer, and "the upheaving of one of the Aeolian islands, previous to a volcanic eruption.

Aristotle proposed that the cause of earthquakes was a gas or vapor (anathymiaseis) that was trapped inside the earth and trying to escape, following other Greek authors Anaxagoras, Empedocles and Democritus.

He was thus critical of Empedocles's materialist theory of a "survival of the fittest" origin of living things and their organs, and ridiculed the idea that accidents could lead to orderly results.

[97][98] Instead, he practiced a different style of science: systematically gathering data, discovering patterns common to whole groups of animals, and inferring possible causal explanations from these.

From the data he collected and documented, Aristotle inferred quite a number of rules relating the life-history features of the live-bearing tetrapods (terrestrial placental mammals) that he studied.

[130] Aristotle believed the chain of thought, which ends in recollection of certain impressions, was connected systematically in relationships such as similarity, contrast, and contiguity, described in his laws of association.

Aristotle identified such an optimum activity (the virtuous mean, between the accompanying vices of excess or deficiency[35]) of the soul as the aim of all human deliberate action, eudaimonia, generally translated as "happiness" or sometimes "well-being".

This is distinguished from modern approaches, beginning with social contract theory, according to which individuals leave the state of nature because of "fear of violent death" or its "inconveniences".

[146] Aristotle believed that although communal arrangements may seem beneficial to society, and that although private property is often blamed for social strife, such evils in fact come from human nature.

[171][172] Among countless other achievements, Aristotle was the founder of formal logic,[173] pioneered the study of zoology, and left every future scientist and philosopher in his debt through his contributions to the scientific method.

[40][174][175] Taneli Kukkonen, observes that his achievement in founding two sciences is unmatched, and his reach in influencing "every branch of intellectual enterprise" including Western ethical and political theory, theology, rhetoric, and literary analysis is equally long.

[176] Aristotle has been called the father of logic, biology, political science, zoology, embryology, natural law, scientific method, rhetoric, psychology, realism, criticism, individualism, teleology, and meteorology.

[205][206] Moses Maimonides (considered to be the foremost intellectual figure of medieval Judaism)[207] adopted Aristotelianism from the Islamic scholars and based his Guide for the Perplexed on it and that became the basis of Jewish scholastic philosophy.

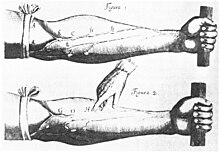

Harvey demonstrated the circulation of the blood, establishing that the heart functioned as a pump rather than being the seat of the soul and the controller of the body's heat, as Aristotle thought.

[220] In 1985, the biologist Peter Medawar could still state in "pure seventeenth century"[221] tones that Aristotle had assembled "a strange and generally speaking rather tiresome farrago of hearsay, imperfect observation, wishful thinking and credulity amounting to downright gullibility".

[226] Practising zoologists are unlikely to adhere to Aristotle's chain of being, but its influence is still perceptible in the use of the terms "lower" and "upper" to designate taxa such as groups of plants.

[236] Reference to them is made according to the organization of Immanuel Bekker's Royal Prussian Academy edition (Aristotelis Opera edidit Academia Regia Borussica, Berlin, 1831–1870), which in turn is based on ancient classifications of these works.

[247]: 5 Some time later, the Kingdom of Pergamon began conscripting books for a royal library, and the heirs of Neleus hid their collection in a cellar to prevent it from being seized for that purpose.

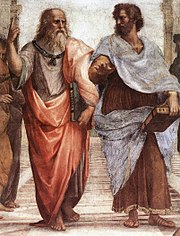

[247]: 6–8 Aristotle has been depicted by major artists including Lucas Cranach the Elder,[249] Justus van Gent, Raphael, Paolo Veronese, Jusepe de Ribera,[250] Rembrandt,[251] and Francesco Hayez over the centuries.

Among the best-known depictions is Raphael's fresco The School of Athens, in the Vatican's Apostolic Palace, where the figures of Plato and Aristotle are central to the image, at the architectural vanishing point, reflecting their importance.