Article Three of the United States Constitution

Section 2 also gives Congress the power to strip the Supreme Court of appellate jurisdiction, and establishes that all federal crimes must be tried before a jury.

[4] Proposals have been made at various times for organizing the Supreme Court into separate panels; none garnered wide support, thus the constitutionality of such a division is unknown.

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, frequently called the court-packing plan,[6] was a legislative initiative to add more justices to the Supreme Court proposed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly after his victory in the 1936 presidential election.

The term "good behaviour" is interpreted to mean that judges may serve for the remainder of their lives, although they may resign or retire voluntarily.

A judge may also be removed by impeachment and conviction by congressional vote (hence the term good behavior); this has occurred fourteen times.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction.

In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

Their judicial power does not extend to cases which are hypothetical, or which are proscribed due to standing, mootness, or ripeness issues.

The Supreme Court held that, though the United States was a defendant, the case in question was not an actual controversy; rather, the statute was merely devised to test the constitutionality of a certain type of legislation.

They were free to diverge from English precedents and from each other on the vast majority of legal issues which had never been made part of federal law by the Constitution, and the U.S. Supreme Court could do nothing, as it would ultimately concede in Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938).

The Congress may not, however, amend the Court's original jurisdiction, as was found in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803) (the same decision which established the principle of judicial review).

The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise will instead of judgement, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body.

In the last-minute rush, however, Federalist Secretary of State John Marshall had neglected to deliver 17 of the commissions to their respective appointees.

Bringing their claims under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the appointees, including William Marbury, petitioned the Supreme Court for the issue of a writ of mandamus, which in English law had been used to force public officials to fulfill their ministerial duties.

Marbury posed a difficult problem for the court, which was then led by Chief Justice John Marshall, the same person who had neglected to deliver the commissions when he was the Secretary of State.

However, Justice Marshall contended that the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional, since it purported to grant original jurisdiction to the Supreme Court in cases not involving the States or ambassadors[citation needed].

The ruling thereby established that the federal courts could exercise judicial review over the actions of Congress or the executive branch.

The Constitution has erected no such single tribunal, knowing that to whatever hands confided, with the corruptions of time and party, its members would become despots.

[18]Clause 3 of Section 2 provides that Federal crimes, except impeachment cases, must be tried before a jury, unless the defendant waives their right.

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.

A contrast is therefore maintained with the English law, whereby crimes including conspiring to kill the King or "violating" the Queen, were punishable as treason.

In Ex Parte Bollman, 8 U.S. 75 (1807), the Supreme Court ruled that "there must be an actual assembling of men, for the treasonable purpose, to constitute a levying of war.

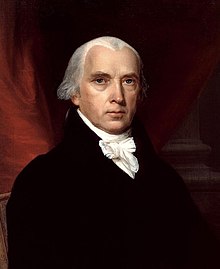

James Wilson wrote the original draft of this section, and he was involved as a defense attorney for some accused of treason against the Patriot cause.

Joseph Story wrote in his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States of the authors of the Constitution that: they have adopted the very words of the Statute of Treason of Edward the Third; and thus by implication, in order to cut off at once all chances of arbitrary constructions, they have recognized the well-settled interpretation of these phrases in the administration of criminal law, which has prevailed for ages.

But as new-fangled and artificial treasons have been the great engines by which violent factions, the natural offspring of free government, have usually wreaked their alternate malignity on each other, the convention have, with great judgment, opposed a barrier to this peculiar danger, by inserting a constitutional definition of the crime, fixing the proof necessary for conviction of it, and restraining the Congress, even in punishing it, from extending the consequences of guilt beyond the person of its author.Based on the above quotation, it was noted by the lawyer William J. Olson in an amicus curiae in the case Hedges v. Obama that the Treason Clause was one of the enumerated powers of the federal government.

[22] He also stated that by defining treason in the U.S. Constitution and placing it in Article III "the founders intended the power to be checked by the judiciary, ruling out trials by military commissions.

As James Madison noted, the Treason Clause also was designed to limit the power of the federal government to punish its citizens for 'adhering to [the] enemies [of the United States by], giving them aid and comfort.

'"[22] Section 3 also requires the testimony of two different witnesses on the same overt act, or a confession by the accused in open court, to convict for treason.

[24] In Cramer v. United States, 325 U.S. 1 (1945), the Supreme Court ruled that "[e]very act, movement, deed, and word of the defendant charged to constitute treason must be supported by the testimony of two witnesses.

The two witnesses, according to the decision, are required to prove only that the overt act occurred (eyewitnesses and federal agents investigating the crime, for example).