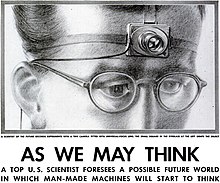

As We May Think

Bush expresses his concern for the direction of scientific efforts toward destruction, rather than understanding, and explicates a desire for a sort of collective memory machine with his concept of the memex that would make knowledge more accessible, believing that it would help fix these problems.

Shortly after the publication of this essay, Bush coined the term "memex" in a letter written to the editor of Fortune magazine.

As described, Bush's memex was based on what was thought, at the time, to be advanced technology of the future: ultra high resolution microfilm reels, coupled to multiple screen viewers and cameras, by electromechanical controls.

For example, Bush states in his essay that: The combination of optical projection and photographic reduction is already producing some results in microfilm for scholarly purposes, and the potentialities are highly suggestive.

"As We May Think" predicted (to some extent) many kinds of technology invented after its publication, including hypertext, personal computers, the Internet, the World Wide Web, speech recognition, and online encyclopedias such as Wikipedia: "Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready-made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified.

"[3] Bush envisioned the ability to retrieve several articles or pictures on one screen, with the possibility of writing comments that could be stored and recalled together.

He believed people would create links between related articles, thus mapping the thought process and path of each user and saving it for others to experience.

Today, storage has greatly surpassed the level imagined by Vannevar Bush, The Encyclopædia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox.

Bush urges that scientists should turn to the massive task of creating more efficient accessibility to our fluctuating store of knowledge.

He argues that the instruments are at hand which, if properly developed, will give society access to and command over the inherited knowledge of the ages.

If humanity were able to obtain the "privilege of forgetting the manifold things he does not need to have immediately at hand, with some assurance that he can find them again if proven important" only then "will mathematics be practically effective in bringing the growing knowledge of atomistic to the useful solution of the advanced problems of chemistry, metallurgy, and biology".

[1] To exemplify the importance of this concept, consider the process involved in 'simple' shopping: "Every time a charge sale is made, there are a number of things to be done.

"[1] Due to the convenience of the store's central device, which rapidly manages thousands of these transactions, the employees may focus on the essential aspects of the department such as sales and advertising.

[1] Improved technology has become an extension of our capabilities, much as how external hard drives function for computers so they may reserve memory for more practical tasks.

"There may be millions of fine thoughts, and the account of the experience on which they are based, all encased within stone walls of acceptable architectural form; but if the scholar can get at only one a week by diligent search, his synthesis are not likely to keep up with the current scene.

"[1] Bush believes that the tools available in his time lacked this feature, but noted the emergence and development of ideas such as the Memex, a cross referencing system.

Bush concludes his essay by stating that: The applications of science have built man a well-supplied house, and are teaching him to live healthily therein.

Yet, in the application of science to the needs and desires of man, it would seem to be a singularly unfortunate stage at which to terminate the process, or to lose hope as to the outcome.

[note 3] A possible future device would be a walnut-sized camera strapped to the head of the wearer that can take a photo at the squeeze of a hand, and develop it.

For example, punched card sorters and telephone exchanges are both search machines: the sorter can quickly produce a stack of cards listing, for example, all employees who live in Trenton, New Jersey and know the Spanish language, and a telephone exchange can quickly connect to the line specified by a number sequence.

Bush proceeds to describe in detail a management system for a department store, where a salesperson enters customer and product information, which a central machine uses to update inventory, credit sales, adjust accounts, and charge customers, using analog devices such as punched cards, dry photography, microfilms, Valdemar Poulsen's magnetic wire recorder, and so on.

Pushing on levers allows users to flip through a microfilmed book, moving forward or backward at variable speeds.

[note 11] Bush describes a use scenario, where the user is studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English longbow in the Crusades.

Lawyers, patent attorneys, and other knowledge workers will use the memex to store their associative trails accumulated over their professional life.

In their introduction to a paper discussing information literacy as a discipline, Johnston and Webber write Bush's paper might be regarded as describing a microcosm of the information society, with the boundaries tightly drawn by the interests and experiences of a major scientist of the time, rather than the more open knowledge spaces of the 21st century.

He outlines a version of information science as a key discipline within the practice of scientific and technical knowledge domains.