Vannevar Bush

The memex, which he began developing in the 1930s (heavily influenced by Emanuel Goldberg's "Statistical Machine" from 1928) was a hypothetical adjustable microfilm viewer with a structure analogous to that of hypertext.

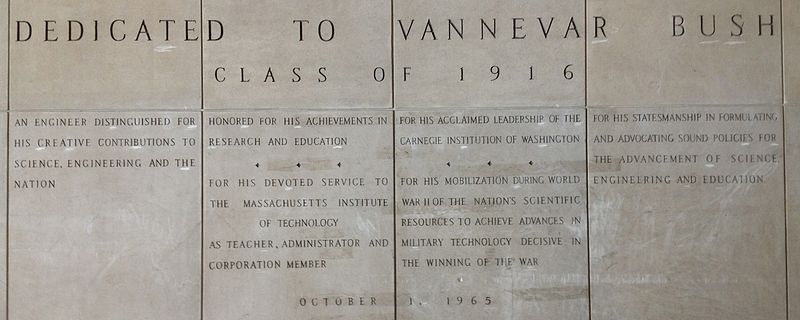

As chairman of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), and later director of OSRD, Bush coordinated the activities of some six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare.

[2] He was the third child and only son of Richard Perry Bush, the local Universalist pastor, and his wife Emma Linwood (née Paine), the daughter of a prominent Provincetown family.

[12] Bush accepted a job with Tufts, where he became involved with the American Radio and Research Corporation (AMRAD), which began broadcasting music from the campus on March 8, 1916.

[13] Bush left Tufts in 1919, although he remained employed by AMRAD, and joined the Department of Electrical Engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he worked under Dugald C. Jackson.

[20] Bush taught Boolean algebra, circuit theory, and operational calculus according to the methods of Oliver Heaviside while Samuel Wesley Stratton was President of MIT.

[27] Bush clashed over leadership of the institute with Cameron Forbes, CIW's chairman of the board, and with his predecessor, John Merriam, who continued to offer unwanted advice.

This decision was supported by the chief of the United States Army Air Corps, Major General Henry H. Arnold, and by the head of the navy's Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Admiral Arthur B. Cook, who between them were planning to spend $225 million on new aircraft in the year ahead.

Concerned about the lack of coordination in scientific research and the requirements of defense mobilization, Bush proposed the creation of a general directive agency in the federal government, which he discussed with his colleagues.

He had the secretary of NACA prepare a draft of the proposed National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) to be presented to Congress, but after the Germans invaded France in May 1940, Bush decided speed was important and approached President Franklin D. Roosevelt directly.

Through the President's uncle, Frederic Delano, Bush managed to set up a meeting with Roosevelt on June 12, 1940, to which he brought a single sheet of paper describing the agency.

Taffy Bowen and John Cockcroft of the Tizard Mission then produced a cavity magnetron, a device more advanced than anything the Americans had seen, with a power output of around 10 kW at 10 cm,[42] enough to spot the periscope of a surfaced submarine at night from an aircraft.

[52] His most difficult problems, and also greatest successes, were keeping the confidence of the military, which distrusted the ability of civilians to observe security regulations and devise practical solutions,[53] and opposing conscription of young scientists into the armed forces.

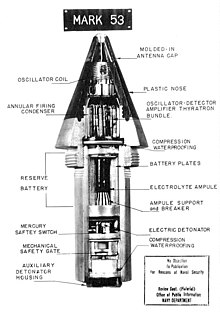

A radar set, along with the batteries to power it, was miniaturized to fit inside a shell, and its glass vacuum tubes designed to withstand the 20,000 g-force of being fired from a gun and 500 rotations per second in flight.

[60] "If one looks at the proximity fuze program as a whole," historian James Phinney Baxter III wrote, "the magnitude and complexity of the effort rank it among the three or four most extraordinary scientific achievements of the war.

Before the war, Bush had gone on the record as saying, "I don't understand how a serious scientist or engineer can play around with rockets",[63] but in May 1944, he was forced to travel to London to warn General Dwight Eisenhower of the danger posed by the V-1 and V-2.

Bush reorganized the committee, strengthening its scientific component by adding Tuve, George B. Pegram, Jesse W. Beams, Ross Gunn and Harold Urey.

To control it, he created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself—although he never attended a meeting—Wallace, Bush, Conant, Stimson and the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George Marshall.

Oppenheimer's calculations, which Bush had George Kistiakowsky check, estimated that the critical mass of a sphere of Uranium-235 was in the range of 2.5 to 5 kilograms, with a destructive power of around 2,000 tons of TNT.

[72] After conferring with Brigadier General Lucius D. Clay about the construction requirements, Bush drew up a submission for $85 million in fiscal year 1943 for four pilot plants, which he forwarded to Roosevelt on June 17, 1942.

Roosevelt approved a Military Policy Committee recommendation stating that information given to the British should be limited to technologies that they were actively working on and should not extend to post-war developments.

[77] In July 1943, on a visit to London to learn about British progress on antisubmarine technology,[78] Bush, Stimson, and Bundy met with Anderson, Lord Cherwell, and Winston Churchill at 10 Downing Street.

The Quebec Agreement merged the two atomic bomb projects, creating the Combined Policy Committee with Stimson, Bush and Conant as United States representatives.

He was able to meet with Samuel Goudsmit and other members of the Alsos Mission, who assured him that there was no danger from the German project; he conveyed this assessment to Lieutenant General Bedell Smith.

"[88] Bush introduced the concept of the memex during the 1930s, which he imagined as a form of memory augmentation involving a microfilm-based "device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.

"[88] He wanted the memex to emulate the way the brain links data by association rather than by indexes and traditional, hierarchical storage paradigms, and be easily accessed as "a future device for individual use ... a sort of mechanized private file and library" in the shape of a desk.

Bush felt that basic research was important to national survival for both military and commercial reasons, requiring continued government support for science and technology; technical superiority could be a deterrent to future enemy aggression.

"[99] In July 1945, the Kilgore bill was introduced in Congress, proposing the appointment and removal of a single science administrator by the president, with emphasis on applied research, and a patent clause favoring a government monopoly.

In contrast, the competing Magnuson bill was similar to Bush's proposal to vest control in a panel of top scientists and civilian administrators with the executive director appointed by them.

At a public memorial subsequently held by MIT,[123] Jerome Wiesner declared "No American has had greater influence in the growth of science and technology than Vannevar Bush".

![Looking down from above at a room at an intricate mechanical device which fills the room. In the background, a man sits at a desk next to a filing cabinet.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Cambridge_differential_analyser.jpg/220px-Cambridge_differential_analyser.jpg)