Asana

More recently, studies have provided evidence that they improve flexibility, strength, and balance; to reduce stress and conditions related to it; and specifically to alleviate some diseases such as asthma[3][4] and diabetes.

[13][14] The eight limbs are, in order, the yamas (codes of social conduct), niyamas (self-observances), asanas (postures), pranayama (breath work), pratyahara (sense withdrawal or non-attachment), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (realization of the true Self or Atman, and unity with Brahman, ultimate reality).

[c][28] The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (15th century) specifies that of these 84, the first four are important, namely the seated poses Siddhasana, Padmasana, Bhadrasana and Simhasana.

[34] The Gheranda Samhita (late 17th century) again asserts that Shiva taught 84 lakh of asanas, out of which 84 are preeminent, and "32 are useful in the world of mortals.

"[36] The scholar Norman Sjoman comments that a continuous tradition running all the way back to the medieval yoga texts cannot be traced, either in the practice of asanas or in a history of scholarship.

[37] From the 1850s onwards, a culture of physical exercise developed in India to counter the colonial stereotype of supposed "degeneracy" of Indians compared to the British,[40][41] a belief reinforced by then-current ideas of Lamarckism and eugenics.

[46][47] Singleton notes that poses close to Parighasana, Parsvottanasana, Navasana and others were described in Niels Bukh's 1924 Danish text Grundgymnastik eller primitiv gymnastik[38] (known in English as Primary Gymnastics).

[36] These in turn were derived from a 19th-century Scandinavian tradition of gymnastics dating back to Pehr Ling, and "found their way to India" by the early 20th century.

[50] He combined asanas with Indian systems of exercise and modern European gymnastics, having according to the scholar Joseph Alter a "profound" effect on the evolution of yoga.

[51] In 1925, Paramahansa Yogananda, having moved from India to America, set up the Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles, and taught yoga, including asanas, breathing, chanting and meditation, to tens of thousands of Americans, as described in his 1946 Autobiography of a Yogi.

"[36] Sjoman argues that Krishnamacharya drew on the Vyayama Dipika[54] gymnastic exercise manual to create the Mysore Palace system of yoga.

[75] Surya Namaskar can be seen as "a modern, physical culture-oriented rendition" of the simple ancient practice of prostrating oneself to the sun.

Sjoman notes that the names of asanas have been used "promiscuous[ly]", in a tradition of "amalgamation and borrowing" over the centuries, making their history difficult to trace.

Though called essentials, they all retard one's progress," while early yogis often practised extreme austerities (tapas) to overcome what they saw as the obstacle of the body in the way of liberation.

[93] Bernard named the purpose of Hatha Yoga as "to gain control of the breath" to enable pranayama to work, something that in his view required thorough use of the six purifications.

He adds that they bring agility, balance, endurance, and "great vitality", developing the body to a "fine physique which is strong and elastic without being muscle-bound".

But, Iyengar states, their real importance is the way they train the mind, "conquer[ing]" the body and making it "a fit vehicle for the spirit".

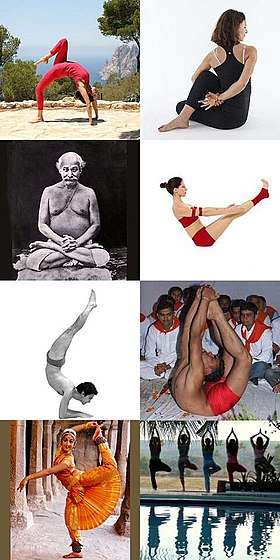

[97] Iyengar saw it as significant that asanas are named after plants, insects, fish and amphibians, reptiles, birds, and quadrupeds; as well as "legendary heroes", sages, and avatars of Hindu gods, in his view "illustrating spiritual evolution".

[99] The message is, Iyengar explains, that while performing asanas, the yogi takes the form of different creatures, from the lowest to the highest, not despising any "for he knows that throughout the whole gamut of creation ... there breathes the same Universal Spirit."

[101] Heinz Grill considers the soul in our human existence to be a central link between the manifest body and the unmanifest spirit.

[109] In a secular context, the journalists Nell Frizzell and Reni Eddo-Lodge have debated (in The Guardian) whether Western yoga classes represent "cultural appropriation".

(HYP 1.44–49)[119] These claims lie within a tradition across all forms of yoga that practitioners can gain supernatural powers, but with ambivalence about their usefulness, since they may obstruct progress towards liberation.

[120] Hemachandra's Yogashastra (1.8–9) lists the magical powers, which include healing, the destruction of poisons, the ability to become as small as an atom or to go wherever one wishes, invisibility, and shape-shifting.

[121] The asanas have been popularised in the Western world by claims about their health benefits, attained not by medieval hatha yoga magic but by the physical and psychological effects of exercise and stretching on the body.

Broad argues that while the health claims for yoga began as Hindu nationalist posturing, it turns out that there is ironically[115] "a wealth of real benefits".

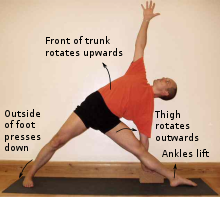

[115] Physically, the practice of asanas has been claimed to improve flexibility, strength, and balance; to alleviate stress and anxiety, and to reduce the symptoms of lower back pain.

[5] There is evidence that practice of asanas improves birth outcomes[4] and physical health and quality of life measures in the elderly,[4] and reduces sleep disturbances[3] and hypertension.

Postures are held for a relatively long period compared to other schools of yoga; this allows the muscles to relax and lengthen, and encourages awareness in the pose.

[142][143] Ashtanga Vinyasa practice emphasises aspects of yoga other than asanas, including drishti (focus points), bandhas (energy locks), and pranayama.

[158][159] Ian Fleming's 1964 novel You Only Live Twice has the action hero James Bond visiting Japan, where he "assiduously practised sitting in the lotus position.