Assyrian continuity

[2][a] Due to an initial long-standing shortage of historical sources beyond the Bible and a handful of inaccurate works by a few later classical European authors, many Western historians prior to the early 19th century believed Assyrians (and Babylonians) to have been completely annihilated, although this was never the view in the region of Mesopotamia itself or surrounding regions in West Asia, where the name of the land and people continued to be applied.

The last period of ancient Assyrian history is now regarded to be the long post-imperial period from the 6th century BC through to the 7th century AD when Assyria was known as Athura and Asoristan, during which the Akkadian language gradually went extinct but other aspects of Assyrian culture, such as religion, traditions, and naming patterns, and the Akkadian influenced East Aramaic dialects specific to Mesopotamia survived in a reduced but highly recognizable form before giving way to specifically native forms of Eastern Rite Christianity.

In addition, Aramaic also replaced other Semitic languages such as Hebrew, Phoenician, Arabic, Edomite, Moabite, Amorite, Ugarite, Dilmunite, and Chaldean among non-Aramean peoples without prejudicing their origins and identity.

[2] The population of Upper Mesopotamia was largely Christianized between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, with Mesopotamian religion enduring among Assyrians in small pockets until the late Middle Ages.

[21][22] Before the 19th century, the prevalent belief in Biblically influenced western scholarship was that ancient Assyria and Babylonia had been literally annihilated due to provoking divine wrath.

[23] This belief was reinforced through archaeologists in the Middle East initially not finding many remains fitting with the conventional European image of ancient cities, with stone columns and great sculptures, beyond those of ancient Persia;[23] Assyria and other Mesopotamian civilizations left no magnificent ruins above ground—all that remained to see were huge grass-covered mounds in the plains which travellers at times believed to simply be natural features of the landscape.

[20] Early European archaeologists in the Middle East were also for the most part more interested in confirming Biblical truth through their excavations than to spend time on new interpretations of the evidence they discovered.

As late as 1925, the Assyriologist Sidney Smith wrote that "The disappearance of the Assyrian people will always remain a unique and striking phenomenon in ancient history.

[29] Though in the past regarded as a "post-Assyrian" age, Assyriologists today consider the last period of ancient Assyrian history to be the long post-imperial period,[29][30] extending from 609 BC to around AD 250 with the destruction of the semi- independent Assyrian states of Assur, Osroene, Adiabene, Beth Nuhadra and Beth Garmai by the Sassanid Empire, or to the end of Sassanid ruled Asoristan and the Islamic Conquest around 637 AD, and support a continuity into the present day.

[29] Though the centuries that followed the fall of Assyria are characterized by a distinct lack of surviving sources from the region in comparison to previous eras,[29] the idea that Assyria was rendered uninhabited and desolated stems from the contrast with the richly attested Neo-Assyrian period, not from the actual extant sources from the post-imperial period, which although reduced, remain unbroken through to the modern era.

[31] Two Neo-Babylonian texts discovered at the city of Sippar in Babylonia attest to there being royally appointed governors at both Assur and Guzana, another Assyrian site in the north.

[32] Individuals with Assyrian names are attested at multiple sites in Assyria and Babylonia during the Neo-Babylonian Empire, including Babylon, Nippur, Uruk, Sippar, Dilbat and Borsippa.

The Assyrians in Uruk apparently continued to exist as a community until the reign of the Achaemenid king Cambyses II (r. 530–522 BC) and were closely linked to a local cult dedicated to Ashur.

[35] Under the Seleucid and Parthian empires, further efforts were made to revitalize Assyria and the ancient great cities began to be resettled,[36] with the predominant portion of the population remaining native Assyrian.

[42] Though this second golden age of Assur came to an end with the conquest, sack and destruction of the city by the Sasanian Empire c. AD 240–250,[43] the inscriptions, temples, continued celebration of festivals and the wealth of theophoric elements (divine names) in personal names of the Parthian period illustrate a strong continuity of traditions dating back to circa 21st century BC, and that the most important deities of old Assyria were still worshipped at Assur more than 800 years after the Assyrian Empire had been destroyed.

[2] Though many foreign states ruled over the Assyrian heartland in the millennia following the empire's fall, there is no evidence of any large scale influx of immigrants that replaced the original population,[2] which instead continued to make up a significant portion of the region's people until Mongol and Timurid massacres in the late 14th century.

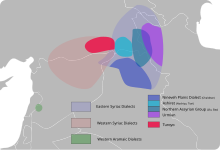

[16] The modern distinction between "Assyrian" and "Syrian" is the result of ancient Greek historians and cartographers, who designated the Levant as "Syria" and Mesopotamia as "Assyria".

[55] Though not used by the overall Syriac-speaking community in the Middle Ages, the term ʾāthorāyā did survive as a self-identity throughout the period as it was the typically used designation for a Syriac Christian from Mosul (ancient Nineveh) and its vicinity.

[57] In large part, tales from the Sasanian period and later times were invented narratives, based on ancient Assyrian history but applied to local and current landscapes.

[60] Medieval tales written in Syriac, such as that of Behnam, Sarah, and the Forty Martyrs, for instance by and large characterize Sennacherib as an archetypical pagan king assassinated as part of a family feud, whose children convert to Christianity.

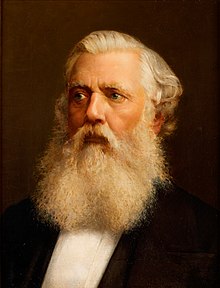

The British traveller Claudius Rich (1787–1821) referenced "Assyrian Christians" in Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan and on the site of Ancient Nineveh (published posthumously in 1836, though describing an 1820 journey).

This was not an isolated phenomenon: Middle Eastern nationalism, probably influenced by developments in Europe, also began to be strongly expressed in other communities during this time, such as among the Armenians, Arabs, Kurds and Turks.

[6] In the Syriac Orthodox Church, officials have been important part of advancing secular Assyrianism, then later reducing it by creating of separate "Syrian"[b] or "Arameans" identities.

The patriarchal residence was later moved to Syria and after the Simele massacre, Ignatius Aphrem I took an anti-Assyrian stance, which came to influence the religious mindset of the Syriac Orthodox community.

[82][9] From the 9th century BC onwards, Aramaic became the de facto lingua franca, with Akkadian becoming relegated to a language of the political elite (i.e. governors and officials).

[9] By the time of Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC), the Assyrian kings employed both Akkadian and Aramaic-language royal scribes, confirming the rise of Aramaic to a position of an official language used by the imperial administration.

[10] A recorded drop in the number of cuneiform documents late in the reign of Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC) could indicate a greater shift to Aramaic, often written on perishable materials like leather scrolls or papyrus,[80] though it could perhaps alternatively be attributed to political instability in the empire.

[83] The denizens of Assur and other former Assyrian population centers under Parthian rule, who clearly connected themselves to ancient Assyria, wrote and spoke Aramaic.

[2] Historians of other fields have also supported Assyrian continuity, such as Richard Nelson Frye,[93] Philip K. Hitti,[94] Patricia Crone,[95] Michael Cook,[95] Mordechai Nisan,[96] Aryo Makko[97] and Joshua J.

[98] Other scholars supporting continuity include, among others, the linguist Judah Segal,[99] the political scientist James Jupp,[100] the genocide researcher Hannibal Travis,[101][102] and the geneticists Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza,[103] Mohammad Taghi Akbari, Sunder S. Papiha, Derek Frank Roberts and Dariush Farhud.