Shalmaneser V

Though Shalmaneser V's brief reign is poorly known from contemporary sources, he remains known for the conquest of Samaria and the fall of the Kingdom of Israel, though the conclusion of that campaign is sometimes attributed to his successor, Sargon II, instead.

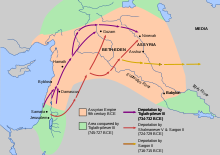

Shalmaneser V is known to have campaigned extensively in the lands west of the Assyrian heartland, warring not only against the Israelites, but also against the Phoenician city-states and against kingdoms in Anatolia.

Though he successfully annexed some lands to the Assyrian Empire, his campaigns resulted in long and drawn-out sieges lasting several years, some being unresolved at the end of his reign.

It is possible that Sargon II was entirely unrelated, which would make Shalmaneser V the final king of the Adaside dynasty, which had ruled Assyria for almost a thousand years.

The name Shalmaneser, rendered by contemporaries as Salmānu-ašarēd in Assyria and Šulmānu-ašarēd in Babylonia, was only ever borne by Assyrian monarchs and never given to anyone other than a king.

Further contents of the letters record several activities conducted by Shalmaneser while he was crown prince, such as detaining emissaries who had passed through certain cities without his permission, and the transportation of goods.

Shalmaneser does not appear to have conducted any large construction projects in the great cities of the Assyrian heartland, such as Assur or Nimrud,[20] and it is plausible that he spent most of his short reign waging war.

[21] There is only a single preserved contemporary source for Shalmaneser's reign in Babylonia, a legal document concerning a disputed sale of a slave, dated to his third regnal year.

[22] Shalmaneser's coronation month, Tebeth, was very late in the year, corresponding to December–January, meaning that it is unlikely that he undertook any significant activities in 727 BC.

The Assyrian Eponym Chronicle, which records significant events for each year in Assyria, is fragmentary in the period covered by Shalmaneser's reign.

[25] It seems that Shalmaneser was relatively unopposed as king in Babylonia, though he appears to have faced some resistance from the Chaldean tribes in the south.

[30] The popular history author Susan Wise Bauer wrote in 2007 that Sargon might have finished the siege, which had been slow, inefficient and still ongoing at the time of Shalmaneser's death.

Their reconstruction of events place the beginning of the siege in 725 or 724 BC, and its resolution in 722 BC near the end of Shalmaneser's reign, and believe that Sargon's inscriptions relating to Samaria may be referencing another incident in which Sargon was forced to put down a large revolt in Syria, which involved the population of Samaria.

The 1st century AD Romano-Jewish historian Josephus records a campaign by the Assyrian king Eloulaios against the coastal cities of Phoenicia.

The 2nd century BC Greek historian Menander of Ephesus records a five-year siege of Tyre as part of an Assyrian war in Phoenicia, probably taking place during Shalmaneser's reign.

If the siege lasted for five years, it must have been unresolved by the time of Shalmaneser's death, with Sargon II possibly abandoning the hostile policy against the city after becoming king.

Shalmaneser is also known to have warred against the kingdom of Tabal in Anatolia, as Sargon mentions in his inscriptions that his "predecessor" defeated and deported the Tabalian king Hullî to Assyria.

An awkward succession is clearly indicated by the fact that out of all of Sargon's numerous preserved inscriptions, only a single one mentions Shalmaneser's fate in any detail, recording him as a godless tyrant who robbed Assur, Assyria's ceremonial center, of its traditional rights and privileges:[10][33] Shalmaneser, who did not fear the king of the world, whose hands have brought sacrilege in this city [Assur], put on his people, he imposed the compulsory work and a heavy corvée, paid them like a working class.

As attested in other inscriptions, Sargon did not see the injustices described as actually having been imposed by Shalmaneser V. Other inscriptions by Sargon state that the tax exemptions of important cities like Assur and Harran had been revoked "in ancient times" and the compulsory work described would have been conducted in the reign of Tiglath-Pileser, not Shalmaneser.

[33] Unless Shalmaneser somehow fled Assyria and took refuge in one of the surrounding enemy states (which there is no evidence for), it can be assumed that he was killed upon his deposition.

It seems clear from surviving sources that Sargon's rise to throne was opposed by a significant faction of Assyrians who supported either Shalmaneser or his rightful heir-apparent.

This is based on Sargon's inscriptions recording the king in his early reign as dealing with over six thousand "guilty Assyrians" through resettlement.

[36] The idea that he was Tiglath-Pileser's son is accepted by many modern historians, though treated with considerable caution,[37] but he is not believed to have been the legitimate heir and next-in-line after Shalmaneser.

It would then be possible that the objects inscribed with Banitu's name actually belonged to Atalia, who had inherited them from the previous queen.

The equation of Iabâ with Banitu cannot be proven with certainty, as the etymological origin (possibly Arabic rather than West-Semitic) and meaning of "Iabâ" cannot be conclusively proven, and the name Banitu could just as likely be derived from the Akkadian word bānītu ("[divine] creatress") as banītu ("beautiful").

Examinations of the skeletons found in the tomb revealed that both women died at the age of about 30–35 and that their deaths were separated by 20–50 years.

The Assyriologist Saana Svärd defended the equation in 2015, stating that it was possible that Atalia died during the reign of Sargon II's successor Sennacherib and was buried in the same grave as Banitu, 20–50 years after the prior burial.