Astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century,[1][2] that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects.

[3][4][5][6][7] Different cultures have employed forms of astrology since at least the 2nd millennium BCE, these practices having originated in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as signs of divine communications.

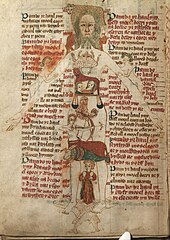

[10][11][12] Nonetheless, prior to the Enlightenment, astrology was generally considered a scholarly tradition and was common in learned circles, often in close relation with astronomy, meteorology, medicine, and alchemy.

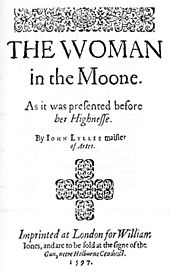

Astrological references appear in literature in the works of poets such as Dante Alighieri and Geoffrey Chaucer, and of playwrights such as Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare.

[26] Farmers addressed agricultural needs with increasing knowledge of the constellations that appear in the different seasons—and used the rising of particular star-groups to herald annual floods or seasonal activities.

[32] The ancient Arabs that inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the advent of Islam used to profess a widespread belief in fatalism (ḳadar) alongside a fearful consideration for the sky and the stars, which they held to be ultimately responsible for every phenomena that occurs on Earth and for the destiny of humankind.

[12] Cicero, in De Divinatione, leveled a critique of astrology that some modern philosophers consider to be the first working definition of pseudoscience and the answer to the demarcation problem.

Against the Astrologers was the fifth section of a larger work arguing against philosophical and scientific inquiry in general, Against the Professors (Πρὸς μαθηματικούς, Pros mathematikous).

[45] By the 1st century BCE, there were two varieties of astrology, one using horoscopes to describe the past, present and future; the other, theurgic, emphasising the soul's ascent to the stars.

[47] The first definite reference to astrology in Rome comes from the orator Cato, who in 160 BCE warned farm overseers against consulting with Chaldeans,[48] who were described as Babylonian 'star-gazers'.

[50] The 2nd-century Roman poet and satirist Juvenal complains about the pervasive influence of Chaldeans, saying, "Still more trusted are the Chaldaeans; every word uttered by the astrologer they will believe has come from Hammon's fountain.

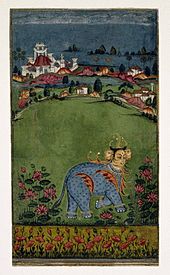

[53] The main texts upon which classical Indian astrology is based are early medieval compilations, notably the Bṛhat Parāśara Horāśāstra, and Sārāvalī by Kalyāṇavarma.

[72] This was in opposition to the tradition carried by the Arab astronomer Albumasar (787–886) whose Introductorium in Astronomiam and De Magnis Coniunctionibus argued the view that both individual actions and larger scale history are determined by the stars.

[73] In the late 15th century, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola forcefully attacked astrology in Disputationes contra Astrologos, arguing that the heavens neither caused, nor heralded earthly events.

Catherine de Medici paid Michael Nostradamus in 1566 to verify the prediction of the death of her husband, king Henry II of France made by her astrologer Lucus Gauricus.

[78] Ephemerides with complex astrological calculations, and almanacs interpreting celestial events for use in medicine and for choosing times to plant crops, were popular in Elizabethan England.

[79] In 1597, the English mathematician and physician Thomas Hood made a set of paper instruments that used revolving overlays to help students work out relationships between fixed stars or constellations, the midheaven, and the twelve astrological houses.

[14][15] One English almanac compiler, Richard Saunders, followed the spirit of the age by printing a derisive Discourse on the Invalidity of Astrology, while in France Pierre Bayle's Dictionnaire of 1697 stated that the subject was puerile.

The Society hosted banquets, exchanged "instruments and manuscripts", proposed research projects, and funded the publication of sermons that depicted astrology as a legitimate biblical pursuit for Christians.

[109] The constellations of the Zodiac of western Asia and Europe were not used; instead the sky is divided into Three Enclosures (三垣 sān yuán), and Twenty-Eight Mansions (二十八宿 èrshíbā xiù) in twelve Ci (十二次).

Some of the practices of astrology were contested on theological grounds by medieval Muslim astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna.

[126][127][128] There is no proposed mechanism of action by which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth that does not contradict basic and well understood aspects of biology and physics.

[16][17] Those who have faith in astrology have been characterised by scientists including Bart J. Bok as doing so "...in spite of the fact that there is no verified scientific basis for their beliefs, and indeed that there is strong evidence to the contrary".

[140]: 34 What if throughout astrological writings we meet little appreciation of coherence, blatant insensitivity to evidence, no sense of a hierarchy of reasons, slight command over the contextual force of critieria, stubborn unwillingness to pursue an argument where it leads, stark naivete concerning the efficacy of explanation and so on?

[151] Scientists reject these mechanisms as implausible[151] since, for example, the magnetic field, when measured from Earth, of a large but distant planet such as Jupiter is far smaller than that produced by ordinary household appliances.

[154] Charpak and Broch, noting this, referred to astrology based on the tropical zodiac as being "...empty boxes that have nothing to do with anything and are devoid of any consistency or correspondence with the stars.

Charpak and Broch noted that, "There is a difference of about twenty-two thousand miles between Earth's location on any specific date in two successive years", and that thus they should not be under the same influence according to astrology.

[172] In 1953, the sociologist Theodor W. Adorno conducted a study of the astrology column of a Los Angeles newspaper as part of a project examining mass culture in capitalist society.

[173]: 327 Adorno concluded that astrology is a large-scale manifestation of systematic irrationalism, where individuals are subtly led—through flattery and vague generalisations—to believe that the author of the column is addressing them directly.

[193] William Shakespeare's attitude towards astrology is unclear, with contradictory references in plays including King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, and Richard II.