Attachment in adults

[1] Attachment theory, initially studied in the 1960s and 1970s primarily in the context of children and parents, was extended to adult relationships in the late 1980s.

The working models of children found in Bowlby's attachment theory form a pattern of interaction that is likely to continue influencing adult relationships.

Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby founded modern attachment theory on studies of children and their caregivers.

Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver continued to conduct research on attachment theory in adult relationships.

Romantic relationships, for example, serve as a secure base that help people face the surprises, opportunities, and challenges life presents.

For example, Fraley and Shaver[8] describe the "central propositions" of attachment in adults as follows: Compare this with the five "core propositions" of attachment theory listed by Rholes and Simpson:[9] While these two lists clearly reflect the theoretical interests of the investigators who created them, a closer look reveals a number of shared themes.

The descriptions of adult attachment styles offered below are based on the relationship questionnaire devised by Bartholomew and Horowitz[14] and on a review of studies by Pietromonaco and Barrett.

[17] Many professionals, such as Sue Johnson, have developed several treatments for adults and couples using principles from Ainsworth and Bowlby's attachment theory.

Research evidence finds that a secure attachment style promotes a smooth transition from adolescence into emerging adulthood.

While these individuals tend to suppress their feelings and may appear unaffected by their emotions, research indicates that they still have strong physiological reactions to emotionally-laden situations and content.

Working models help guide behavior by allowing children to anticipate and plan for caregiver responses.

When Hazen and Shaver extended attachment theory to romantic relationships in adults, they also included the idea of working models.

Relational schemas help guide behavior in relationships by allowing people to anticipate and plan for partner responses.

The unique contribution of relational schemas to working models is the information about the way interactions with attachments usually unfold.

To demonstrate that working models are organized as relational schemas, Baldwin and colleagues created a set of written scenarios that described interactions dealing with trust, dependency, and closeness.

According to Baldwin: A person may have a general working model of relationships, for instance, to the effect that others tend to be only partially and unpredictably responsive to one's needs.

The middle level of the hierarchy contains relational schemas for working models that apply to different types of relationships (e.g., friends, parents, lovers).

Adults with insecure (anxious or avoidant) attachment styles tend to have lower satisfaction and commitment within their relationships.

Secure attachment styles may lead to more constructive communication and more intimate self-disclosures, which in turn increase relationship satisfaction.

[56][64] Other mechanisms by which attachment styles may influence relationship satisfaction include emotional expressiveness,[65][66] strategies for coping with conflict,[60] and perceived support from partners.

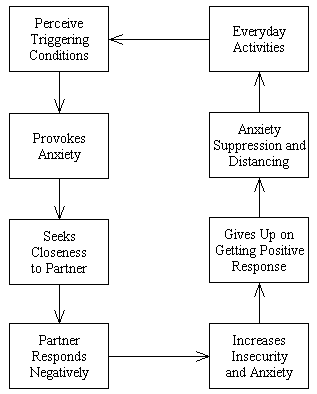

The hyperactivation and attachment avoidance strategies lead to more negative thoughts and less creativity in handling problems and stressful situations.

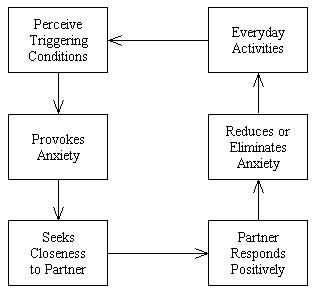

From this perspective, it would benefit people to have attachments who are willing and able to respond positively to the person's request for closeness, so that they can use security-based strategies for dealing with their anxiety.

Adults in relationships with a partner who responds consistently and positively to requests for closeness tend to have secure attachments, and in return, they seek more support, while adults in relationships with a partner who typically is inconsistent in reacting positively or regularly reject requests for support tend to have another attachment style.

Bowlby writes: Attachment theory regards the propensity to make intimate emotional bonds to particular individuals as a basic component of human nature, already present in germinal form in the neonate and continuing through adult life into old age.

Jealousy refers to the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that occur when a person believes a valued relationship is threatened by a rival.

The fact, however, that an older child often reacts in this way even when his mother makes a point of being attentive and responsive suggests that more is involved.

The pioneer experiments of Levy (1937) also indicate that the mere presence of a baby on a mother's lap is sufficient to make an older child much more clinging.

This might be attributable to feelings of inferiority and fear, which were especially characteristic of the anxiously attached and which might be expected to inhibit direct expressions of anger.

Anxiously attached individuals are more likely to use emotionally focused coping strategies and pay more attention to the experienced distress.

[94] The anxious and avoidant attachment has been found to predict interpersonal electronic surveillance (IES) (i.e., "Facebook stalking").